The tell-tale sign of antibodies

Determining COVID-19 immunity with blood testing

Determining COVID-19 immunity with blood testing

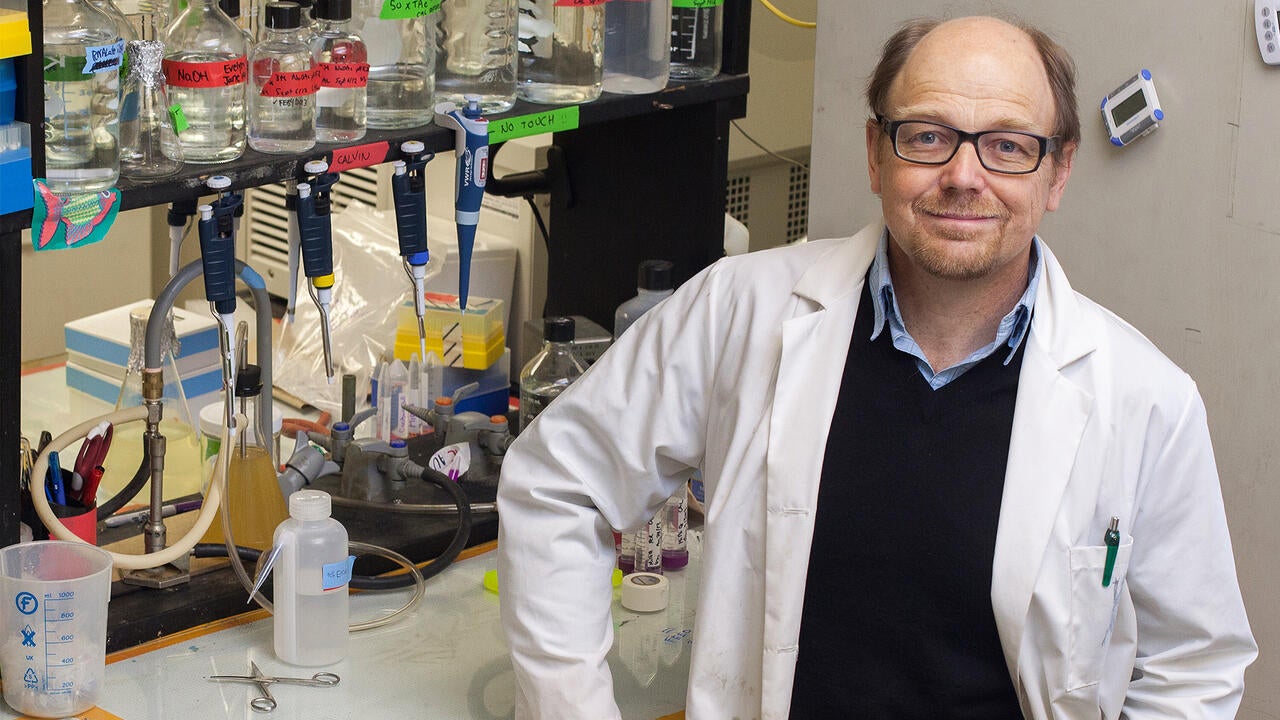

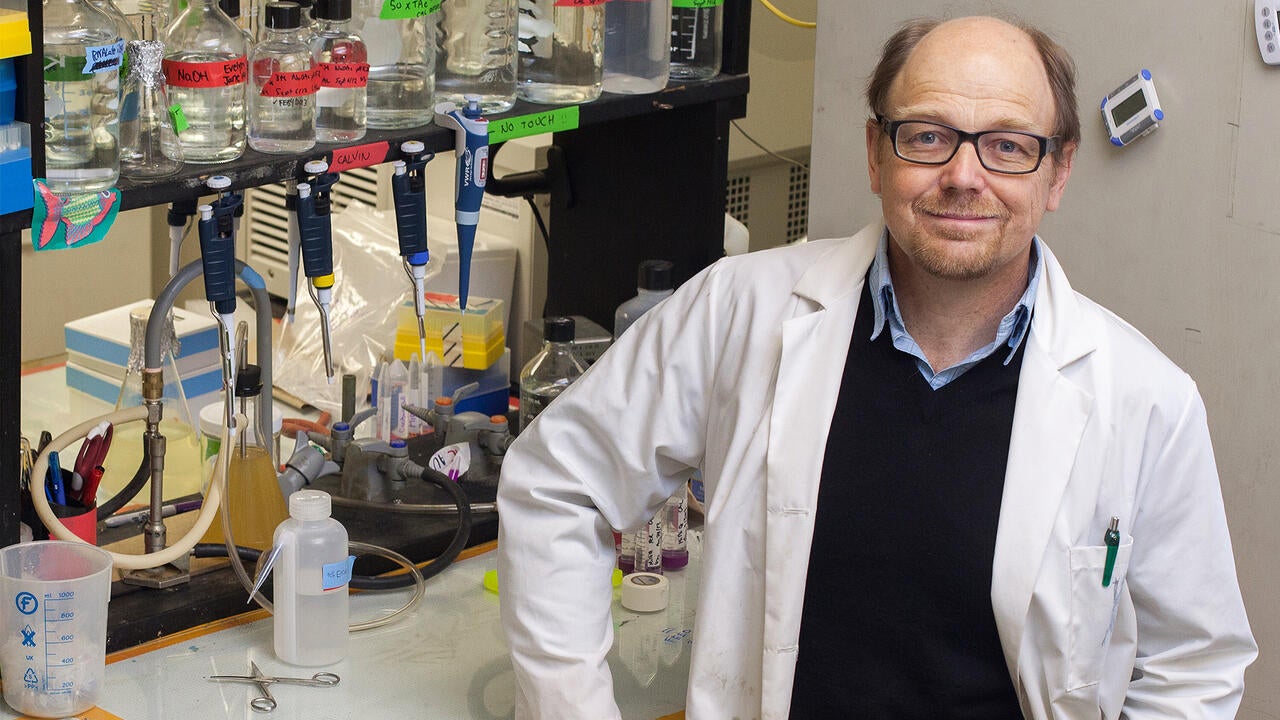

By Elizabeth Kleisath Faculty of ScienceWhen the University’s research labs shut down for quarantine, biology professor Brian Dixon pivoted some of his research away from blood testing in fish, into looking at blood testing in humans. Instead of sitting around and waiting for his labs to open again, Dixon wanted to use his time and knowledge of biology and immunology to contribute to the global need for understanding and overcoming COVID-19.

“My lab happens to do a lot of testing in fish because aquaculture is important — but it’s all blood testing, it’s all looking for molecules in blood,” Dixon explains. “So, we realized that it would be very easy for us to pivot to testing for COVID-19.”

Dixon and his lab are exploring ways to test blood samples for antibody markers, which indicate if someone has previously been exposed to COVID-19. Antibody testing is becoming more important as quarantine restrictions are softened, because it gives an indication of an individual’s immunity to COVID-19, as well as how long the immunity lasts, therefore indicating who may be at a greater risk for infection.

Dixon goes on to explain that when a body is infected with a virus, the immune system creates molecules known as antibodies.

“Antibodies function similar to a lock and key, because each antibody is specifically designed by our bodies to identify one specific virus — such as SARS-Cov-2, the virus that causes the illness COVID-19 — and bind to it,” he says. “Once created, these antibodies then stay in our blood stream, ready to identify and defend against the virus in the future.”

By creating a test for COVID-specific antibodies, scientists can identify individuals who have already been exposed to a virus and therefore might be more immune.

Infection causing viruses, including COVID-19, produce two different types of antibodies — one about four days after the initial infection and the other about 14 days later. Identifying which antibodies someone produces indicates how recent a COVID-19 infection is, and if someone has already been exposed to and are now protected from the virus.

Working in collaboration with Marc Aucoin from the Faculty of Engineering, Dixon is using a standard biochemical test known as an ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) which can detect these two types of antibodies. Dixon is using ELISA to answer questions about how long the antibodies last in our bodies and how dilute the blood samples can be while still reliably detecting antibodies.

“The results of the first samples we have tested match perfectly with the known COVID-19 infection status of the patients, including a weaker antibody presence in patients who did not have a strong, definitive COVID-19 infection,” Dixon says. “Therefore, we are confident in the antibody test’s ability to accurately predict the presence and strength of a patient’s antibody response.”

Additionally, he and Aucoin plan to expand the research to look at how mutations in the virus could change the body’s immune response, and also investigate if there is a correlation between the amount of antibodies an individual produces and their outcome to COVID-19. They also have plans to research stimulating antibody production from artificial viruses that look similar to the SARS-Cov-2 virus but can’t replicate, which could be used in developing a potential vaccine.

Read more

Rapid Novor secures $5-million USD as its team works to decode antibodies for potential medical treatments for COVID-19 and other illnesses

Read more

Working together, researchers at McMaster University and the University of Waterloo are searching for how the SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the lungs – and they’re challenging what has become an accepted truth about the virus.

Read more

Researchers at the University of Waterloo are developing a new method to decrease the likelihood of contracting HIV.

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.