Climate change puts Arctic winters on thin ice

Climate change causes dramatic thinning of ice on Arctic lakes and cuts winter ice season by almost a month over 60-year-span, Waterloo study finds

Climate change causes dramatic thinning of ice on Arctic lakes and cuts winter ice season by almost a month over 60-year-span, Waterloo study finds

By Staff Marketing and Strategic CommunicationsArctic lakes have been freezing up later in the year and thawing earlier, creating an ice season about 24 days shorter than it was in 1950, a University of Waterloo study has found.

The research, sponsored by the European Space Agency (ESA), also reveals that climate change has dramatically affected the thickness of lake ice at the coldest point in the season: In 2011, Arctic lake ice was up to 38 centimetres thinner than it was in 1950.

“We’ve found that the thickness of the ice has decreased tremendously in response to climate warming in the region,” said lead author Cristina Surdu, a PhD student in Waterloo’s Department of Geography and Environmental Management. “When we saw the actual numbers we were shocked at how dramatic the change has been. It’s basically more than a foot of ice by the end of winter, so it’s very significant.”

Research team documents magnitude of climate change

The study of more than 400 lakes of the North Slope of Alaska, is the first time researchers have been able to document the magnitude of lake-ice changes in the region over such a long period of time, says author Claude Duguay, a University of Waterloo professor and member of the Interdisciplinary Centre on Climate Change.

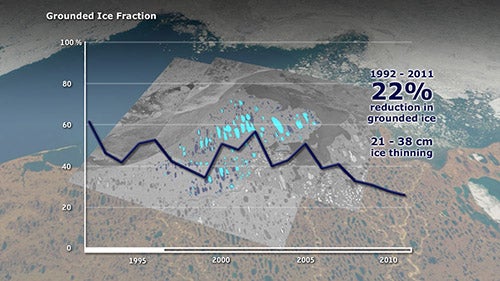

The research team used satellite radar imagery from ESA to determine that 62 per cent of the lakes in the region froze to the bottom in 1992. By 2011, only 26 per cent of lakes froze down to the bed, or bottom of the lake. Overall, there was a 22 per cent reduction in what the researchers call “grounded ice” from 1992 to 2011.

Radar signals tell the story of thinning ice

Researchers were able to tell the difference between a fully frozen lake and one that had not completely frozen to the bottom, because satellite radar signals behave very differently, depending on presence or absence of water underneath the ice.

Radar signals are absorbed into the sediment under the lake when it is frozen to the bottom, explains Surdu. However, when there is water under the ice with bubbles, the beam bounces back strongly towards the radar system. Therefore, lakes that are completely frozen show up on satellite images as very dark while those that are not frozen to the lake bed are bright.

Model simulation provides data back to 1950

Researchers used the Canadian Lake Ice Model (CLIMo) to determine ice cover and lake ice thickness for those years before 1991, when satellite images are not available.

The model simulations show that lakes in the region froze almost six days later and broke up about 18 days earlier in the winter of 2011 compared to the winter of 1950.

Thin ice impacts wildlife, permafrost and Northern communities

The changes in ice and the shortened winter, affect Northern communities that depend on ice roads to transport goods, said Surdu. Shorter ice-cover seasons may also lead to shifts in lake algal productivity as well as thawing of permafrost under lake beds.

More broadly, the dramatic changes in lake ice may also contribute to further warming of the region because open water on lakes, although to a lesser extent than open sea water, contribute to warmer air temperatures, said Surdu.

(GettyImages/ Rosella De Berti)

Read more

Study reveals changes International Olympic and Paralympic Committees could implement to keep Games viable and safer for athletes

Read more

An ambitious research collaboration with Habitat for Humanity is reimagining home ownership across Waterloo Region and Canada

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.