Waterloo engineering prof makes discovery about how wounds heal

Research is key to understanding how cells move and could one day help prevent cancer and birth defects

Research is key to understanding how cells move and could one day help prevent cancer and birth defects

By Staff Marketing and Strategic Communications

A civil engineering researcher is using his expertise in structures to better understand how wounds heal and cells move, which may one day help prevent cancer and birth defects.

"When people think of civil engineering, they probably think of bridges and roads, not the human body," said Wayne Brodland, a professor in Waterloo’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. "Like a number of my colleagues, I study structures, but ones that happen to be very small, and under certain conditions can cause cells to move. The models we build allow us to replicate these movements and figure out how they are driven."

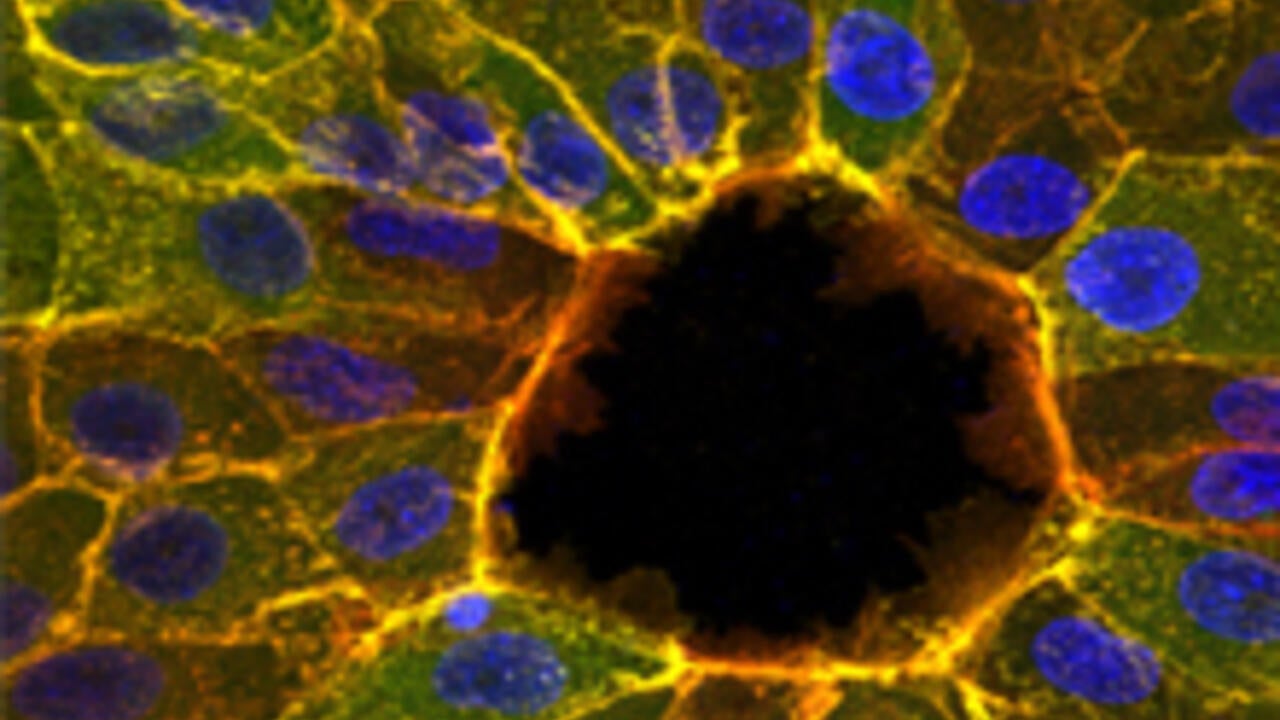

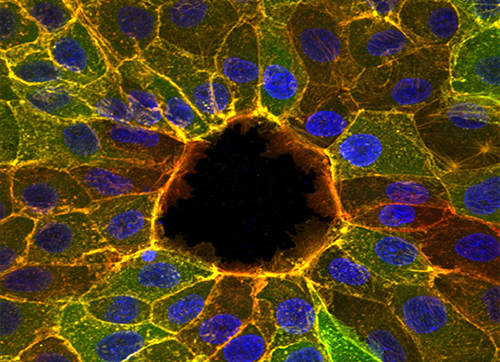

Brodland is developing computational models for studying the mechanical interactions between cells. In this project, he worked with a team of international researchers who found that the way wounds knit together is more complex than we thought. The results were published this week in the journal, Nature Physics.

When you cut yourself, a scar remains, but not so in the cells the team studied. The researchers found that an injury closes by cells crawling to the site and by contraction of a drawstring-like structure that forms along the wound edge. They were surprised to find that the drawstring works fine even when it contains naturally occurring breaks.

This knowledge could be the first step on a long road towards making real progress in addressing some major health challenges.

"The work is important because it helps us to understand how cells move. We hope that someday this knowledge will help us to eliminate malformation birth defects, such as spina bifida, and stop cancer cells from spreading," said Brodland.

The research team was composed of 10 researchers from Spain, France, Singapore and Canada. Brodland is one of the paper's two Canadian co-authors. His contribution received support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Read more

Robots the size of a soccer ball create new visual art by trailing light that represents the “emotional essence” of music

Read more

Waterloo prof leads a team of researchers to improve water quality through a community-focused approach underpinned by technical excellence

Read more

New medical device removes the guesswork from concussion screening in contact sports using only saliva

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.