Text:

Kelley

Teahen

Photography:

Courtesy

of

Debbie

Johnston

"See that rooster over there?" Johnston says, pointing to a carved wooden bird on a pole sitting next to his desk in the president's office at Waterloo. "It's over a weather vane. That's me. Vain rooster."

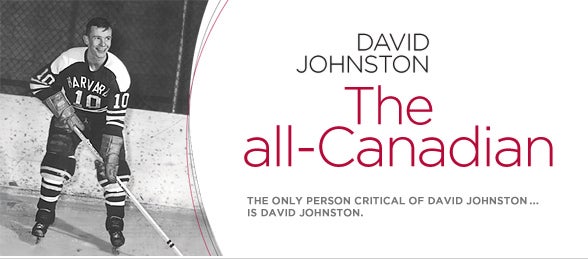

He is referring to how upset it makes him to be bad at any sport. While he has excelled at many - famously becoming an "all-American" when playing hockey at Harvard - he is "terrible at golf and it drives me nuts because I am so vain."

Waterloo's fifth president sees himself as competitive: "not in a cutthroat way, but I like to do well." He smiles, a gleam in his eye. "The world ranking of this university is of great importance to me."

His other self-observed flaws have to do with speed. "I'm impatient, and that's a weakness. I have a sense of urgency that I bring sometimes in an oppressive way into situations. I'm so conscious, there are only 24 hours in a day, and there are so many things to be done, and time's a-wasting." Ancillary to his impatience — beyond a penchant for collecting speeding tickets — is a worry that he sometimes makes decisions too quickly in his urge to move things forward, and that he has "a short attention span."

It's not surprising that a self-aware humility lives at the heart of David Lloyd Johnston, whose life journey has been shaped, as his eldest daughter Debbie observes, by his Canadianness: "He grew up poor in northern Ontario. He got his first job when he was nine, and by 11 he was working in a mechanic's garage. In many other countries, his future would be working in a coal mine or factory. There's no way a poor boy would have the chance to do great things in his life. But my dad was born in a country where doors can be opened irrespective of your socioeconomic background."

Johnston was born on June 28, 1941, in Sudbury, one of three children. His father Lloyd, with a Grade 10 education, worked in hardware sales and moved the family back to his hometown of Sault Ste. Marie when David was in grade school. Johnston's mother, Dorothy, grew up in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and had attended university, "so she certainly encouraged us in school," Johnston says. "It was a bit of a surprise to my dad that my sister, brother, and I were all good students."

By high school, Johnston, in addition to getting top grades and working part-time, was involved "in every sport there was: baseball in summer, football in fall, and hockey in the winter." The possibility of attending the Ivy League Harvard came about because an alumnus of that university was seeking scholar-athletes and connected to David via a Harvard grad who worked at the insect laboratory in the Sault.

The

offer

and

scholarship

were

a

great

opportunity,

but

Johnston

could

not

have

pursued

it

without

"the

help

of

a

whole

community,"

says

his

fifth

and

youngest

daughter,

Sam,

a

director

with

the

Center

for

Social

Innovation

in

Boston.

For

instance,

Johnston

would

hitchhike

to

Toronto

from

Boston

on

school

breaks

and

the

mechanics

at

the

garage

where

he

had

worked

would

find

a

car

for

him

in

Toronto

and

pay

Johnston

to

drive

it

to

Sault

Ste.

Marie.

"That's

left

a

mark

on

him

and

has

had

an

impact

on

his

work,"

Sam

Johnston

says.

"A

mechanic

would

care

enough

to

find

a

way

to

get

him

home

at

Christmas."

At Harvard, Johnston's shining quality was determination, says Toronto lawyer Tom Heintzman, whose lifelong friendship with Johnston started when both Canadians were on the Harvard hockey squad.

"David (who played defence) would catch the puck in his teeth to stop it going in the net. He would do anything to not have anyone score on us. He's not an outstanding physical athlete but he was an all-American because of his determination."

He became very close to his coach, Cooney Weiland, whom Johnston calls an "outstanding teacher." "Cooney would say to me, Johnny, go into the corner and come out with the puck and your teeth. He meant, you win the contest, but you're 150 pounds, and don't think you're going to outmuscle some guy or be tougher: you've got to be smarter. He was a little guy like me, about 5'8", and he always said, little guys have to think differently."

Off the ice, Johnston connected well to the high society of Harvard, but he loves to tell an Icarus-like tale of flying a bit too high away from his humble roots.

"I was invited to a debutante ball at the Ritz Carlton, and the invitation said, black tie. I turned to my roommate and said, this is probably a dance I shouldn't miss but I have a grey tie, I don't think I have a black tie. And he told me, it's not like that."

Johnston had no tuxedo, and rental fees were prohibitive, so he borrowed one from someone else in the dorm: "We were about the same build except he was taller than me and the trousers were too long." The lads decided to turn up the pants, and fasten them inside using scads of white hockey tape. Johnston went off and was "dancing the light cotillion at 2 a.m. when I suddenly realized I was the object of everyone's attention because I was trailing about three yards of white hockey tape behind me."

It's a favourite story, Johnston says, "because it keeps me grounded. Don't get too caught up in your dancing: other people may be watching the hockey tape."

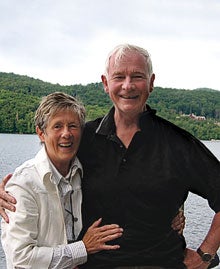

Johnston had left more than family at home: in high school he had dated Sharon Downey, two years younger, whom he remembers first seeing at St. Luke's Anglican Church. During Johnston's third year at Harvard, Sharon's grandmother died. "I had been very fond of her grandmother, and went to visit the family to pay my respects." A slow smile spreads across his face. "And that's when the sparks began to fly again, and we began to date steadily." The couple married in 1964.

In 1963, after completing his arts degree at Harvard, Johnston considered a professional hockey career but ultimately did not pursue that path as he had injured his left hand at the end of high school and permanent nerve damage limited his strength. He decided to pursue legal studies and chose a scholarship opportunity at Cambridge in England "to make a clean break from the game I loved so much" rather than studying in Boston or Toronto or Montreal, with the taunt of NHL teams within reach.

Despite that "clean break," hockey remains a burning passion for Johnston, who has continued to play throughout his academic career. Daughter Debbie, now a lawyer in Ottawa with the federal Department of Justice, remembers her dad "coming home from work at night, and going out to hose a rink in our backyard at night." He didn't think daughters would be interested in hockey but they all took up the sport in their teens or 20s. "One of his proudest moments was when my sister Sharon, who played hockey at Harvard like he did, broke his thumb with a slap shot. He was very, very proud her slap shot was so hard."

Johnston earned a law degree in Cambridge, after which the lure of Canada brought him and Sharon home, where he took up Canadian legal studies at Queen's University; their first daughter, Debbie, was born in Kingston in 1968.

It was at this time that Purdy Crawford, then as now a lawyer at Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt in Toronto, came into Johnston's life. Johnston applied for articling positions and "five minutes into the interview (with Purdy), I said to myself, if they offer me a job, I'll take it."

"I recognized very quickly this guy was very talented," Crawford recalls. "I've always been impressed by his good judgment, impressed by his understanding of the complexity of many things, whether it's medicine or farming. I believe people who read widely have broader vision and make better leaders; they don't have a narrow view of the world. That's David, better than anybody I know."

Crawford, like Johnston, is a man without airs, well known for how he treats all alike in dignity. The Crawford-Johnston style is also shared by Heintzman, who says Johnston has a great gift for treating everyone "absolutely equally. That's a Canadian feeling … it comes more naturally to us as we're a country of immigrants."

Johnston never did make it to Osler's, apart from a few months working on security regulation files with Crawford in the summer of 1966, an exposure that would lead to Johnston becoming one of the country's top writers about securities laws. The dean of the Queen's law school offered Johnston a faculty position for the fall, once he graduated, and Johnston, after much deliberation, decided to try his hand at teaching and research.

In the next years, Johnston's academic career took him and the growing family — five girls in under eight years — to Toronto, then London, Ontario (where he was dean of the Western law school) and finally to McGill in 1979, where he served for 15 years as principal. In an article in the McGill News written when Johnston left, writer Victor Swoboda summarized his presidency in one sentence: "David Johnston never stops running."

He perfected the art of multitasking, whether at home in the cheerfully chaotic household filled with young girls and frequent university dinner guests, squeezing in runs up and down Mont Royal amid a bull-stunning schedule of daily meetings, or negotiating the tense dance between separatist Quebec politics and funding for an English-language university in the late 1980s.

Johnston did not keep a separate office at home, but worked on university files among the children. At the dining room table after dinner, "while we did our homework, he did too," Debbie Johnston says. "My mom explained Dad had a lot of homework because he was a little slower."

Johnston drove his administration team to not coast on the strong reputation of McGill. He was ambitious, and is a man, Heintzman observes, "who is not content to do less than his best, at any time. But he does it in a way that doesn't upset or put down those around him. In law, I see many ambitious people, but they don't have the ability to lead or make others do their best."

Paul Davenport, former president at both University of Alberta and University of Western Ontario, says he was a "little no-account associate professor" at McGill when he first met the new principal, Johnston, at a university teachers' association salary committee meeting. "The next day we crossed paths in the faculty club and he looked me right in the eye and said, 'Hello, Paul.' I was so startled he remembered me that I stuttered and forgot his name!"

Despite this inauspicious start, Davenport became one of many people Johnston has mentored over the years: three years after Davenport became a vice-president at McGill, he was offered his own presidency in Alberta. "David mentored me wonderfully: whatever success I have had is because of the time I've spent with him."

Kevin Lynch, former clerk of the Privy Council, served as the deputy minister at the Department of Industry during the time of the Information Highway Advisory Council, a group Johnston chaired 1994-1997, and says the group did extraordinary work, creating policies that laid the groundwork for achievements such as Canada being the first nation on earth to connect all its schools to the Internet. Johnston, as chair, had to pull together people who normally are at loggerheads in business, such as phone companies and cable companies.

"David's such an optimist," Lynch says. "It's hard to let self-interest prevail when you have an individual like him at the head of the table, thinking such magnificent thoughts for the country: He pulls people up by his optimism and vision and true love for his country. Your own self-interest seems so small by comparison."

Johnston continued to teach law at McGill during these years and developed a close working relationship with John Manley, the industry minister who had appointed him to lead the council, a relationship that turned personal in vintage Johnston family style.

The ever-multi-tasking Johnston also was chair in the same years for the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research and Manley was invited to an institute dinner in 1999, shortly after Johnston had come to Waterloo as president. "I sat at a table beside Sharon, and she talked about the horse farm they had acquired: she told me she was running a bed and breakfast. Stupidly, I took her seriously," he says.

The Manleys, when planning their next trip to the Stratford Festival near Waterloo, called Sharon and said, "We'd like to book a room in your B&B do you have an opening on these dates?" The Johnstons never corrected the illusion, but prepared the guest room and welcomed the Manleys with a big dinner attended by people from the Waterloo tech industry as well as old friend Tom Heintzman, who entertained by playing piano for a singalong in the cleaned-out pig barn.

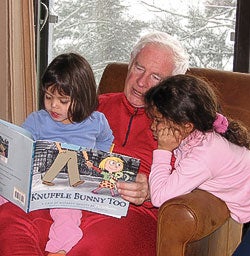

"He loves being around his family; that is so important to him," Debbie Johnston says. "You can see him light up, especially with grandchildren." He loves reading to the grandkids and playing sports with them, whether kicking around a soccer ball or teaching new skills, like waterskiing. He also relaxes with runs and cycling, activities often shared with family members. When asked what he would do if he had an unexpected couple days off, Johnston answers immediately: "First we'd gather as many of our children and our grandchildren as we could and have a great old time; and the next day, my wife and I would go for a long walk, and I'd read a book and she would work on her novel. Reflective times, especially with my wife, are important to me."

Johnston feeds his curiosity and keeps building his astonishing range of knowledge through voracious reading: he regularly ships out books to friends and family members, and reads several volumes at a time. Earlier this fall, he was juggling Ted McWhinney's The Governor General and the Prime Ministers; Edward Rutherfurd's New York and London; and Niall Ferguson's The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World. He had just finished former governor general Adrienne Clarkson's autobiography Heart Matters, and the Millennium trilogy by Stieg Larsson, "which I just found thrilling. My wife found it the usual trash that her husband puts his nose in, but it's good stuff. Those are the kind of books I read for 30 minutes before going to sleep."

His daughters report he also is in the habit of sending summaries of sermons to them via BlackBerry messages, thumb-typed directly from church.

Johnston, in his wide-ranging academic and service career — his resumé lists his service on 14 academic, 29 public agency / government, and 17 business boards or commissions — has been largely silent about his religious faith, out of both "shyness and privacy." But he will say this about what motivates him, and what he will bring to his role as Canada's 28th governor general:

"The core of my religion is the concept of love, and love thy neighbour. You know, every person I meet is my neighbour. Under my beliefs, you treat them with enormous respect; they're God's creatures, and you need to see them as neighbours and love them as neighbours. And it sounds a little hokey, but that's also my sense of public service: I'm enormously privileged to have had the kind of opportunity to serve, and you know, now I have another one. The cup runneth over."