Canadian-German Relations on Display

Recently, Waterloo Centre for German Studies employees Misty Matthews-Roper and James Skidmore caught up with Adèle Hempel, Manager/Curator of the Waterloo Region Museum. The museum is currently hosting “Canada and Germany: Partners from Immigration to Innovation,” on view until 3 September 2018. Adèle was able to answer a few questions for us.

What is the focus of the exhibition “Canada and Germany: Partners from Immigration to Innovation”?

The exhibition gives a brief introduction about immigration of Germans to Canada and also Canadians going over to Germany - it’s a two-way street. It also touches on innovation.

For the innovation part, we weren’t able to get all of the items from the exhibit launched in Ottawa (June 2017); some of the items were on temporary loan and weren’t able to travel. We were very happy to get the lunar rover. That was a real fluke! I happened to be sitting at a dinner and the Chair of the Board of Ontario Drive and Gear, Joerg Stieber, was sitting next to me. We started talking about the museum and our next travelling exhibit, Canada and Germany, and out of the blue he offered “would you like to have a lunar rover?” Having recently arrived here, I had no idea who Mr. Stieber was or what the company did. The rover is the centerpiece of our exhibit!

Lunar Rover on display at the Waterloo Region Museum till 3 September 2018

Which items connected to innovation didn’t come to the Waterloo exhibition?

What was the role of the Waterloo Region Museum in the original exhibition?

Tom Reitz (former manager/curator) submitted a portion of our panel copy to the exhibition’s curator, Peter Finger, who was employed by the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany in Ottawa to produce this exhibition. It’s nice to see that Mr. Finger put in a substantial section on Kitchener-Waterloo. He really wanted to have the exhibition on display here, so he approached us.

Why do you think it’s important for this exhibition to be hosted in Kitchener-Waterloo?

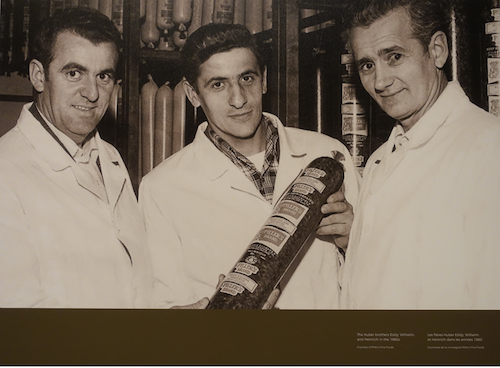

This region is recognized as a capital for German culture in Canada. It’s wonderful for people from the community to come in and see themselves in the exhibition. On the night of the opening, it was heartwarming, for instance, that Willi Huber recognized himself in one of the photographs. How nice is that for people to see themselves in an exhibition!

What are some of the other local connections to the exhibition?

There are lots of local connections here. There’s a section on John Motz and the Berliner Journal. There’s also a display of the skills and trades that came into the region – German immigrants were often well trained in the trades before coming over. The local section starts off with the Mennonite settlers and then moves on to the continental German-speaking peoples who followed them.

Some of the people represented have not been spoken about much, despite the centuries of German settlement in Canada, perhaps because of the wars and the prejudices they engendered. There has been a reticence among some Germans to share their personal stories. It’s time to encourage these stories to be told. At the same time, this exhibit does not shy away from sensitive topics, like the war years.

Which items or stories in the exhibition say something that is particularly noteworthy for you?

Take for example the story of Kurt Günzel. Just the fact that he was a prisoner of war: imagine the feeling of being shipped off to another country, totally removed from family, and when he was freed and sent back to Germany and could live wherever he wanted, chose to return to Canada with his family because he was so impressed with the people and country he had gotten to know.

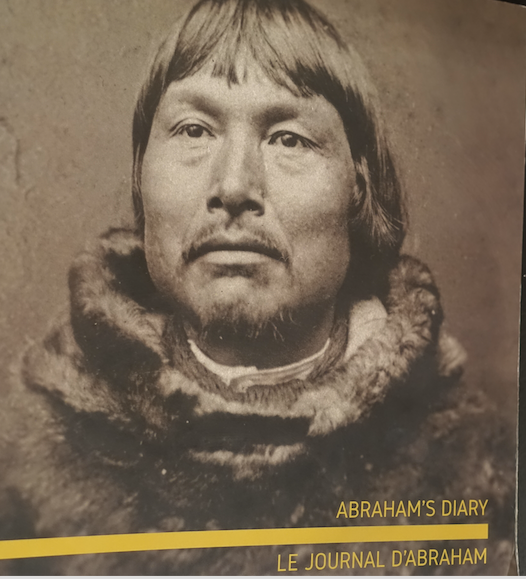

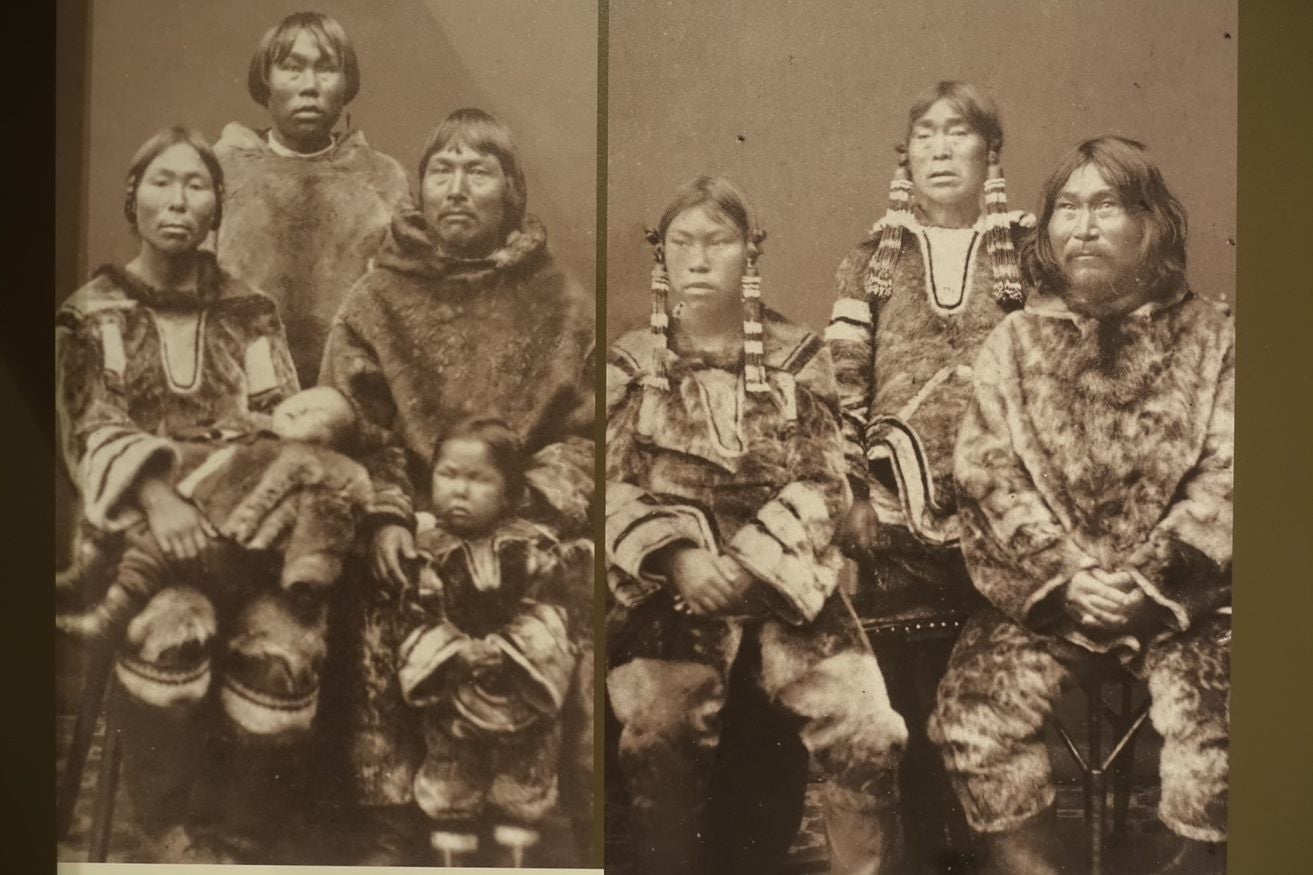

Another story shook me, and I don’t know how well known it is. It’s the story of eight Inuit (Abraham, Ulrike, their two children and four others) known to the Moravian missionaries who worked in Labrador, who were put on display - a little like the Dionne quintuplets – in Europe. Back in the late 19th century, Europeans looked at Aboriginal peoples like specimens to be put on public display. These Inuit all died of smallpox (three died in Germany, the rest in Paris). The exhibit has reproduced some of Abraham’s diaries, which are heart-wrenching to read.

But you also have a positive story about the musical legacy of the Moravians and what they taught the Inuit. While this could be looked upon as the “colonizing” of Indigenous peoples, in this example there is a positive sharing of cultural traditions through the medium of music, and visitors can listen to a recording of music performed by an Inuit choir.

Inuit family and above right picture of Abraham's diary.

We know this exhibition is the tip of the iceberg in terms of relations between Germany and Canada. What remains to be studied - or curated - from your perspective?

I think there’s a significant amount of Canadian history that’s being lost because of the language difference, the Schrift (German style of handwriting) and the Fraktur (German Gothic type). People couldn’t record it properly back in the day and they can’t read it easily now. If you’re trying to do genealogical studies, it’s difficult: Anglophones misspelled German names and/or Anglicized them, so it’s not always easy to trace ancestors. I think there needs to be some concerted effort to study the German documents in local repositories. Some history scholars can’t read German or contract this out to third parties, and one can miss the nuances by approaching it that way.

There’s much history to be discovered, and I think that could bring some people back to their roots more. Some local residents with German heritage have lost touch with their past; they don’t know where their ancestors came from in Europe or why their names are pronounced or spelled the way they are. I look at Bleams Road and that’s just one example - I could give you ten or twelve, and I’ve only lived here for a year!

Our Canadian history can be very mixed up, and it takes students and scholars to disentangle the evidence and put stories together again – like puzzles.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.