The Global Engagement Seminar's ARTS 490, The Future of Nature, was among the 975 Faculty of Arts courses that had to pivot to online delivery in mid-March. The class was deep into preparing final team projects that would have been presented at the public Summit held at the Balsillie School in early April. Along with the Summit cancellation, there would also be no public keynotes by the GES mentors, renowned photographer Edward Burtynsky and prolific scholar and expert on socio-political activism Mike Davis.

Everything changed for everyone everywhere. While not nearly on the scale of COVID-19 impacts worldwide, it seemed like a calamitous thing for the course.

“None of us will forget this experience,” says Katherine Acheson, associate dean of arts for undergraduate programs and acting director of the Global Engagement program. Yet, she adds, the pandemic and lockdown did bring the students face-to-face with a very real global challenge: “they were witness to, and engaged topically with, exactly the kind of complex, swiftly emergent, and devastatingly powerful phenomenon the course is designed to address.”

The cohort of 34 students from all of Waterloo’s six faculties were co-taught by Angela Carter, Associate Professor in Political Science and Brendon Larson, Professor in the School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability – a dream team of combined expertise in social and political aspects of the climate emergency.

Now in its third year, the GES program is a unique Arts initiative supported in part by the Jarislowsky Foundation. Its central strength is that it brings together a diversity of expertise in its mentors, named Jarislowsky Fellows, its faculty instructors, and the students. This year’s challenge to address the future of nature powerfully brought these strengths into focus: the class had to think deeply and critically about our relationship with nature, and to model ways for humanity to readjust ourselves, our views and our actions in the face of environmental crisis.

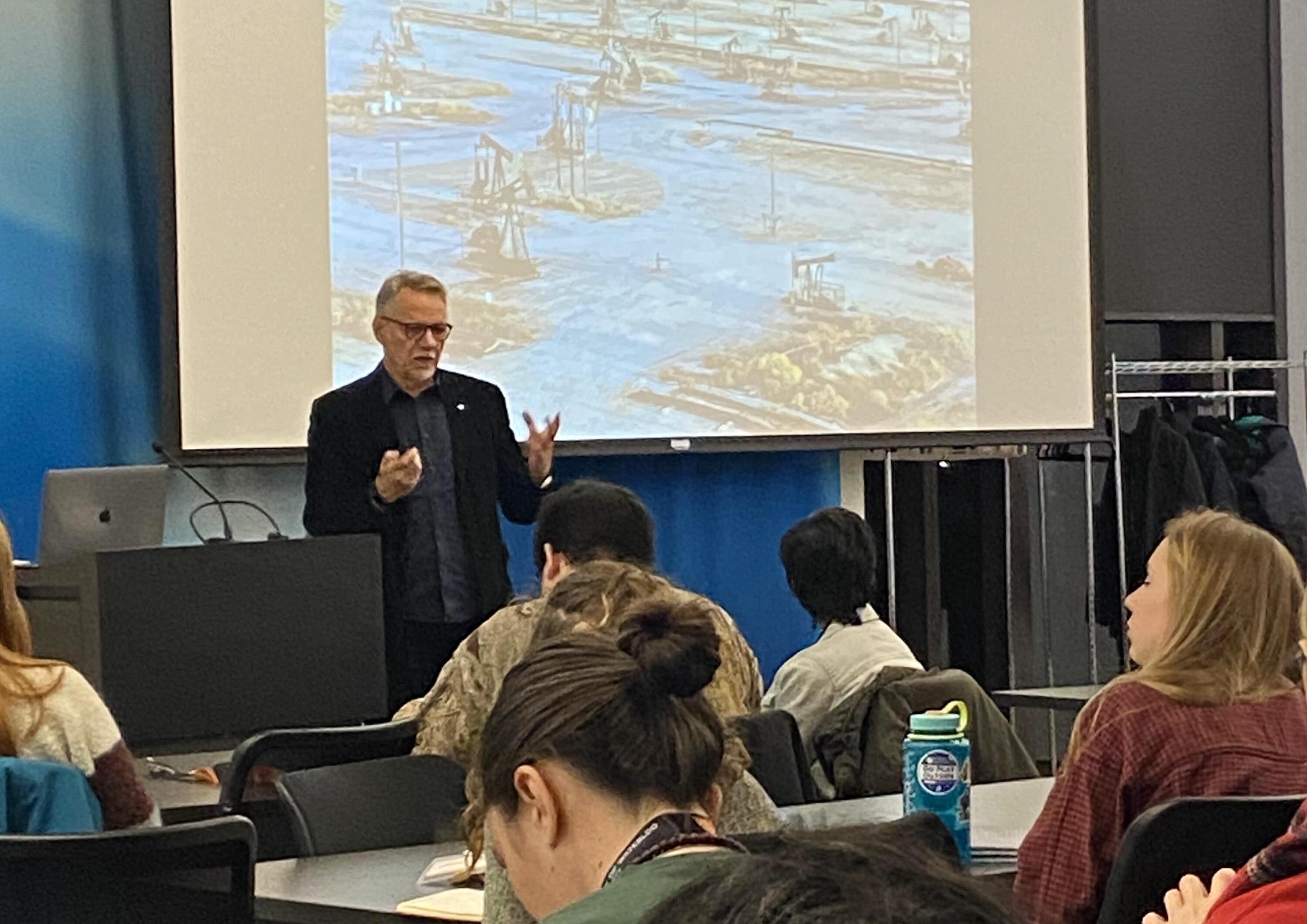

Edward Burtynsky speaks to the Global Engagement students.

Along with fieldtrips, readings, film screenings, and discussions facilitated by professors Carter and Larson, the students had in-person and virtual meetings with Burtynsky and Davis. These meetings were unique opportunities for the students to be able to dissect a reading or film with the authors themselves.

“By the time classes were suspended, the students had spent nine weeks in the company of two brilliant fellows engaging with a broad range of ideas that gave them some key tools for making sense of COVID,” says Carter.

“They had rich discussions on the environmental, economic, and socio-political origins of the global crisis,” Carter continues. “They had grappled with how crises such as these are experienced differently by people in our local communities as well as globally due to longstanding, systematic inequities—and they had debated what might be needed to confront those injustices. They also engaged with more positive and potentially even empowering ways to cope with the anxiety, fear, and paralysis of the climate crisis, ideas that I hope are transferable to our current difficult situation.”

Consultation with Burtynsky and Davis, along with other experts in local community organizations, is a vital aspect of the GES students’ learning and final projects. Fortunately, most of the project teams were able to connect with community members for research interviews, documentation, and filming before the pandemic lockdown.

“Given the current global context, we’re very proud of how well the students were able to adapt their projects and how well they accepted the ‘let-down’ of not being able to work towards the kind of final projects they had hoped for,” says Larson.

"While our present reality has taken a strange and unprecedented turn, the theme we've been discussing these past months, "The Future of Nature", now has a more impactful meaning than ever before. I'm hopeful for each of these intelligent individuals as they move towards graduation and beyond." - Edward Burtynsky, 2020 Jarislowsky Fellow

Like most Waterloo instructors who had to suddenly pivot to online course completion, Carter and Larson recognized that students were dealing with complicated and stressful personal situations. “We encouraged them to scale back and rework their group projects so that they could be presented online. We then made sure that the students had a platform for sharing and responding to each group’s project. Even though we couldn’t have the public Summit event as planned, students still got plenty of feedback on their work.”

The seven team projects address climate issues like food security in the local area, global manufacturing and consumption, greening campus spaces, fossil fuel divestment, interconnections between climate and social systems, and a meditation on nature past, present, and future. Their work was delivered and shared via website, video, online petition, and podcasting.

“The students’ passion for making change shone through,” says Larson of the outcomes. “We’re confident that the projects have set the stage for future contributions they will make.” Echoing the thought, Ethan, a student in the class, commented as the course concluded, “This isn’t an end, it’s just a beginning.”

Three team project examples

- The Food Shakers team produced a documentary video, The Future of Food, that “works to unearth the sustainable food narrative in the Waterloo region” featuring interviews with a variety local growers and producers of vegetables, meat, dairy and honey.

- Living Campus explores greening the UWaterloo campus. The work is “inspired by the tensions and possibilities between informal green spaces and formal managed designs,” with ideas and insights gathered from faculty, graduate students and other members of the campus community.

- Contagious Impact: Divestment as Student Activism is an online petition to encourage fossil fuel divestment by the Universality of Waterloo. “Our goal is to show the value of working across student groups […] when people come together for a specific purpose, voices are amplified, and structural change can happen.”