Engineering a new normal

Faculty researchers and alumni share their COVID-19 research and expert opinions on life now and post-pandemic

Faculty researchers and alumni share their COVID-19 research and expert opinions on life now and post-pandemic

By Brian Caldwell Faculty of EngineeringIt is no exaggeration to say that the silent, unseen coronavirus has turned our lives, institutions and systems upside down and inside out.

Assessing the social, economic and psychological fallout of changes that are both big – millions of people suddenly working from home – and small – elbow bumps instead of time-tested handshakes – will no doubt keep academics busy for years.

For engineers dedicated to the development and application of technology, plus all of its related fields of endeavour, that process of examination, analysis and learning is already well under way.

To help understand and appreciate their work, seven alumni and faculty members of Waterloo Engineering – from a tech entrepreneur who teaches yoga, to a researcher with plans to make buildings immune – were asked about their pandemic insights and initiatives.

Here is a look at how they are both contributing in the here and now, and paying heed to lasting lessons that could help make life after COVID-19 better.

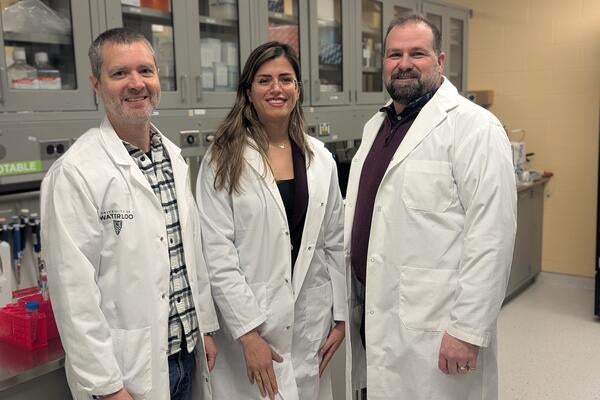

After 15 years as a researcher, Marc Aucoin's work has never been more urgent or more exciting than it is right now.

After 15 years as a researcher, Marc Aucoin's work has never been more urgent or more exciting than it is right now.

Aucoin, a Waterloo Engineering alumnus and chemical engineering professor, is a key member of a team working to develop a DNA-based vaccine for COVID-19 to be delivered via a nasal spray.

“There is a clear feeling we can make a real difference and my entire team has doubled and tripled their efforts since this started,” he says. “It’s all out of a pure desire to help.”

Aucoin (BASc ’00, MASc ’03, chemical engineering) and four core members in his lab are working on the project with Waterloo pharmacy professors Roderick Slavcev and Emmanuel Ho.

Their approach – one of only a handful of similar efforts worldwide – involves engineering synthetic DNA.

That DNA would contain instructions for cells within the body to make particles that resemble SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, but are not harmful.

Once present, the virus-like particles would trigger the body’s immune system to produce antibodies. Particles produced in cultured cells in the lab would also be administered to boost immunity.

“The idea is that if we get the human body to make its own particles and proteins to serve as the vaccine, you achieve a better, stronger overall immune response,” Aucoin says.

With over 100 research teams around the world working on vaccines, even promising approaches face long odds to make it into mass production and ultimately protect people.

Still, researchers logging long days and seven-day weeks to put a Waterloo vaccine in the mix are confident their work will have a lasting impact one way or another.

“Even if we don’t hit it out of the park, we’re learning a lot and this work is still very relevant,” Aucoin says. “It positions us to be prepared to respond to situations like this in the future.”

That old adage about adversity creating strength is holding true for a lot of entrepreneurs who have been put to a severe test during the pandemic.

That old adage about adversity creating strength is holding true for a lot of entrepreneurs who have been put to a severe test during the pandemic.

Janet Boekhorst, a professor at the at Waterloo Engineering, fully expected to find a lot of people struggling when she surveyed entrepreneurs, self-employed workers, and small and medium-sized business owners in Canada to gauge how they were faring.

That was certainly the case, with about half of survey respondents expressing concerns about their ability to keep their businesses afloat.

Boekhorst was surprised and encouraged, however, by reports from many people who have adapted by making changes that could actually strengthen their businesses over the long haul.

“I think it’s the nature of entrepreneurship,” says Boekhorst, who is handling the Canadian portion of an ambitious, 28-country study led by researchers at King’s College London in the United Kingdom.

“Entrepreneurs tend to be good at rolling with the punches. They’re problem-solvers by nature and that is really boding well for a lot of them.”

Examples include brick-and-mortar retailers opening online shops, adding parcel delivery and consequently expanding their customer bases, and restaurants pivoting to take-out when they were forced to shut down, then retaining it as a permanent new revenue stream.

Boekhorst credits the creativity and resilience of entrepreneurs for such successes, as well as the willingness of consumers to accept new ways of doing business during challenging times.

“There has been a lot of exploration and that has really opened up some windows of opportunity,” she says. “It’s great to see people using their skill sets and energy to figure out ways to keep moving forward.”

Forced office closures during the pandemic have demonstrated that many people can work productively from home using online tools and platforms.

Forced office closures during the pandemic have demonstrated that many people can work productively from home using online tools and platforms.

But for Anne Bordeleau, director of the Waterloo School of Architecture, that fact – a surprise to some, mere confirmation to  others – is only the start of an important examination of how we live and work.

others – is only the start of an important examination of how we live and work.

“For architecture, the pandemic brings large questions about interconnectedness and vulnerable populations, but also very simply foregrounds the importance of our built environment,” she says.

Bordeleau wonders, for instance, if people will actually want to work from home – and, if so, how much of the time – even if remote technology continues to make it possible when the health crisis is over.

“For a number of people there is a real concern that their domestic space is now being fully invaded by work,” she says.

That invasion highlights the significance of spaces that are both conducive to work and create clear lines, physically as well as psychologically, between our professional and personal lives.

“Spaces play an extremely important role in terms of framing different activities and establishing boundaries, of distinguishing a place where you can relax and a place where you can work,” Bordeleau says.

She also believes there is growing recognition that shared workplace spaces – even the hallways we take from one meeting to another – are valuable sources of socialization, energy and spontaneous collaboration.

In practical terms, that could lead to offices redesigned to emphasize their informal, impromptu functions and the in-between spaces that ultimately keep us all together.

“Technology is so portable that we think we can work anywhere – and it’s kind of true,” Bordeleau says. “But at the same time, it may also mean that we can relax nowhere, and this situation should make us acutely aware of the role spaces play in framing our activities and interactions.”

After more than a decade of work on a system to protect people in public buildings from biological agents and chemical toxins, Janusz Kozinski is optimistic its time has come.

After more than a decade of work on a system to protect people in public buildings from biological agents and chemical toxins, Janusz Kozinski is optimistic its time has come.

Concerns heightened by the COVID-19 crisis, plus advances in technology, give him hope the system will gain widespread adoption.

“There is a completely different environment now,” says Kozinski, an adjunct professor of chemical engineering at Waterloo. “Many stars have aligned.”

Work on his concept to effectively immunize buildings goes back to the late-2000s, when Kozinski was the engineering dean at the University of Saskatchewan, one of many senior positions he has held. He led a research team in the development of a system to monitor ventilation systems in public buildings such as schools, hospitals and shopping malls.

The system uses a network of sensors and computer software to identify threats, then issue warnings and take steps to neutralize them.

“The key here is to prevent the potential propagation of the harmful agent from one area to another,” Kozinski says.

The system, dubbed eWARN (Early Warning and Response Network), worked well on computer models, in the lab and during limited field trials, but never got much real-world traction.

When the pandemic hit, Kozinski and colleagues at Waterloo and several other Canadian schools revived the concept, tweaking it for detection of the coronavirus.

Ongoing efforts are focused on the use of nanoscale sensors to dramatically improve its response time to split seconds.

In the case of SARS-CoV-2 – or some new variation of it in the future – the system would emit UV light to try to kill it, activate HVAC filters to prevent its spread via ducts and alert people in the detection area to take precautions.

“We believe this will be very, very useful,” Kozinski says. “The whole purpose is to save lives. The next time around we will be much better prepared.”

Kunal Gupta (BSE ’08) couldn’t be less impressed with how the pandemic is highlighting the ability of workers to meet just as often as before it, maybe even more, using remote technology.

Kunal Gupta (BSE ’08) couldn’t be less impressed with how the pandemic is highlighting the ability of workers to meet just as often as before it, maybe even more, using remote technology.

His key take-away from the global health crisis is that less is more, that fewer meetings and less collaboration actually equal more focus and increased productivity.

“Productivity isn’t working more,” he says from his home in New York. “It’s working on the right things at the right times.”

Gupta comes to the question as an entrepreneur who proudly wears two hats.

In his professional life, he is a co-founder and CEO of Polar, a Toronto-based, 25-member company that provides digital advertising technology to hundreds of publishers and advertising agencies in over 30 countries.

As an active and avid volunteer, he works with several mental health organizations, teaches meditation and yoga, and blogs about leadership, mindfulness and technology culture.

Gupta says that by disrupting ordinary life and business, the coronavirus has forced everyone to reflect on what they do and why they do it.

In the process, it has provided a much-needed boost to awareness around the importance of mental health – who hasn’t experienced some anxiety or depression, or seen someone close to them struggling? – and the value of better work-life balance.

“This time has given everybody more mental space,” says Gupta, who started Polar with classmates while he was still an undergraduate student at Waterloo.

“We’ve cut out a lot of what we thought of as essential – and now know isn’t essential – and that has created breathing room for our minds.”

One lasting lesson for companies, he says, is that their employees clearly can be trusted to work from home with little or no supervision and still pull their weight.

“It’s kind of funny that we are surprised by that,” Gupta says. “It took a pandemic for us to get to the point where we have more trust in our people, but that’s fine. We’re here now.”

3D PRINTING PROVES ITS POTENTIAL

When one-size-fits-all just isn’t good enough, additive manufacturing (AM) is up for the challenge.

When one-size-fits-all just isn’t good enough, additive manufacturing (AM) is up for the challenge.

That became clear early in the COVID19 crisis as Mihaela Vlasea and other researchers at the MultiScale Additive Manufacturing (MSAM) Laboratory were flooded with inquiries from doctors, hospital administrators and other healthcare workers in need of help.

The lab’s innovative technology, also known as industrial 3D printing, proved itself nimble enough to quickly produce parts for face shields and frames  for reusable N95 masks to protect medical professionals and patients.

for reusable N95 masks to protect medical professionals and patients.

And because AM processes – essentially printing parts layer by layer and with multiple raw materials – are so flexible, MSAM could customize personal protective equipment to better fit people of different ethnicities, ages, sizes and genders.

One tweak of its mask frames even prevents fogging for users who wear glasses.

“That’s not a problem for us,” says Vlasea, associate research director of the world-class lab. “We just iterate a few times and provide the product.”

The crisis also demonstrated how well local AM facilities can work directly with local clients to design and manufacture the products they need, eliminating long supply chains, speeding up delivery and enabling modifications on the fly.

“Imagine having a tool that you can deploy for multiple purposes very quickly,” says Vlasea, a Waterloo Engineering professor and alumnus (BASc ’08, PhD ’14, mechanical and mechatronics engineering). “The flexibility to print one thing today and another thing tomorrow, or quickly calibrate a product to make it better, is hugely important.”

By boosting awareness of its potential, Vlasea expects high-profile examples of AM providing precise solutions to help speed its adoption by industry leaders now and on the other side of the pandemic.

“An unexpected outcome of an extremely unfortunate situation is that it has shown people this is not a fringe technology or a technology of tomorrow,” she says. “These tools are available today and they can be effectively deployed in sensitive sectors such as healthcare.”

It took office closures during the pandemic to show Mohsen Shahini that employees at the company he co-founded could be just as productive working remotely from home.

It took office closures during the pandemic to show Mohsen Shahini that employees at the company he co-founded could be just as productive working remotely from home.

In a similar way, he believes the forced move to online classes is opening the eyes of educators, students and parents to what technology can bring to higher learning.

“Once we are out of this, you’ll find fewer professors are afraid of technology because they had no choice but to use it,” says  Shahini (PhD ’11, mechatronics engineering), an entrepreneur and Waterloo Engineering alumnus. “That will expedite the transition of classroom learning, which really hasn’t changed much for centuries.”

Shahini (PhD ’11, mechatronics engineering), an entrepreneur and Waterloo Engineering alumnus. “That will expedite the transition of classroom learning, which really hasn’t changed much for centuries.”

Shahini was still working on his doctorate when he launched Top Hat, a learning software company, with former roommate and fellow alumnus Mike Silagadze (BASc ’07, electrical engineering) a decade ago.

Currently, with well over 400 employees and four million users, the Toronto-based company’s core “active learning” product allows students to engage with course content using interactive textbooks and take part in inclass activities, online or in-person, using their mobile devices or laptops.

Last year, Shahini took a leave and launched a startup called Kritik, which develops high-level critical thinking by enabling students to collaborate, provide feedback and analysis, and learn from each other.

Now he sees nothing but growth ahead as changes necessitated by the health crisis showcase the possibilities and increase the acceptance of online learning.

“We expect massive adoption of technology and massive innovation post-pandemic,” he says.

Key questions for Shahini include how institutions will permanently adapt and adopt lessons from the pandemic, and what changes the people who pay to attend them will expect or demand.

“For the first time, there is a challenge to the value proposition of higher education,” he says. “It’s great for students to be on campus, but will it be worth it to spend that much money when most courses can be delivered online? Probably not, but we will have to see how demands and expectations from return on investment in higher education change post-pandemic.”

Article originally published in the October 2020 issue of WEAL

Read more

Researchers engineer bacteria capable of consuming tumours from the inside out

Hand holding small pieces of cut colourful plastic bottles, which Waterloo researchers are now able to convert into high-value products using sunlight. (RecycleMan/Getty Images)

Read more

Sunlight-powered process converts plastic waste into a valuable chemical without added emissions

University of Waterloo researchers Olga Ibragimova (left) and Dr. Chrystopher Nehaniv found that symmetry is the key to composing great melodies. (Amanda Brown/University of Waterloo)

Read more

University of Waterloo researchers uncover the hidden mathematical equations in musical melodies

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.