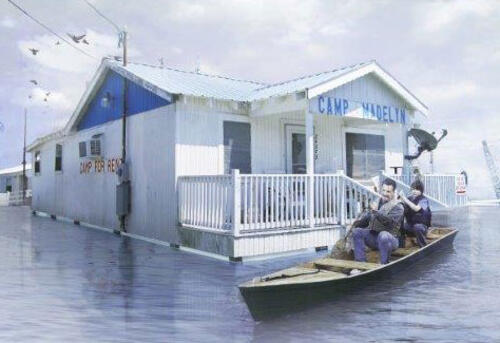

House floats as unique solution to avoid flooding disasters

Elizabeth English, a Waterloo School of Architecture professor, established the Buoyant Foundation Project.

Elizabeth English, a Waterloo School of Architecture professor, established the Buoyant Foundation Project.

By Kira Vermond Faculty of EngineeringIn the days after Hurricane Katrina tore through New Orleans leaving horrific flooding in its wake, Elizabeth English entered the area and managed to get a firsthand look at the devastation.

At the time, English was researching the flight paths of damaging wind-borne debris at the Louisiana State University Hurricane Center. But after witnessing the effects of the natural disaster that left entire neighbourhoods underwater, she changed her research focus.

“I quickly realized that wind was not the big story, it was the water,” says the Waterloo School of Architecture professor and Water Institute member.

Her solution for preserving communities vulnerable to flooding? She makes houses float.

English, who has both an architecture and civil engineering background, studies and designs flood-resistant, amphibious houses that allow homeowners to evacuate them knowing when they return, their homes will have sustained minimal or no damage.

They look like normal houses, but are built on a foundation made from buoyant blocks of EPS (expanded polystyrene, or Styrofoam™) or tanks filled with air. As the area around it floods, the house rises while vertical guidance posts keeps it from floating away. When the water recedes, the house then floats back to the ground.

“People will still leave, but when the water goes away their houses are completely intact with no damage and they can move right back in,” says English, who established the Buoyant Foundation Project.

Not everyone thinks amphibious houses are the answer to building in flood-prone areas of the world; some would like to see all people evacuated from these regions. But English says she’s convinced they’re an important solution for pre-existing communities such as New Orleans that are filled with inhabitants who want to stay in the neighbourhoods they love.

Not backing away from her vision, she moved to Canada and joined the architecture faculty at Waterloo. Now, she’s continuing her work with Waterloo graduate and undergraduate students who have spent time in vulnerable communities around the world, from Nicaragua to Jamaica and Bangladesh.

Closer to home, she’s also in consultation with Canada’s First Nations communities in northern Manitoba where springtime flooding can destroy houses and displace people for years. Even a small amount of water and shifting can create moldy basements and unsafe living conditions.

Example image of a floating house

“The work that I had been doing in Louisiana is applicable to Northern Canadian communities,” she says. “It seemed like a good idea to use the same technology.”

As the co-chair of the first-ever International Conference on Amphibious Architecture Design Engineering, or ICAADE, in Bangkok this summer, she has learned that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution to preventing flood damage. But by gathering likeminded researchers together, new answers are on the horizon.

For instance, her team designed an amphibious house with an extended deck for a rural community in Nicaragua so the homeowners could carry their pigs and chickens with them during a flood.

“In other parts of the world, people don’t have the luxury of evacuating, so they have to stay,” English explains. “It’s a question of preserving lives, as well as livelihood and property.”

Learn more about the Buoyant Foundation Project from Elizabeth English’s interview on TVO’s The Agenda.

Read more

Two University of Waterloo affiliated health-tech companies secure major provincial investment to bring lifesaving innovations to market

Read more

Here are the people and events behind some of this year’s most compelling Waterloo stories

Read more

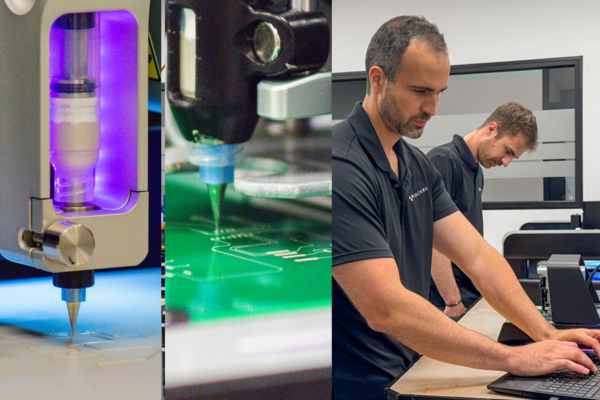

Voltera prints electronics making prototyping faster and more affordable — accelerating research to market-ready solutions

Read

Engineering stories

Visit

Waterloo Engineering home

Contact

Waterloo Engineering

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.