Sheep with a small 'c': Economy and the natural law

“I'm certainly tending toward the post-liberal localism style of sheep farming. 🙂 There's nothing more wholesome (and fun) than a community slaughter day. Fry up the fresh organs for dinner, save the blood for sausage, prepare the hide for tanning, etc. All made easier by the presence of community members. (From personal experience, two people can do the basic meat butchery but more hands are needed to save every part and piece of the animal). We've had group slaughter days on a number of occasions, and I highly recommend it. My hope, over the long term, is that more and more of our needs and wants can be satisfied via our small scale livestock raising endeavours. Clothing, rugs, mattress, leather goods, food (meat, milk, cheese) -- all products to be produced on the home (or village) scale. A local friend of ours (a physicist trained at McGill, who moved to rural Indiana and built himself a strawbale house) has skill in turning sheep hide into parchment -- something I'd never even thought of. The uses for livestock are so numerous, that any kind of sustainable future society will absolutely require them (funny thing is, I am a reformed vegan/vegetarian. Glad I have changed my ways now). Livestock also play a significant role in building soil health!”

[Kristen Giesting: Personal Communication: Kristen is a graduate of SERS, U. Waterloo, and runs a small homesteading in Indiana, USA]

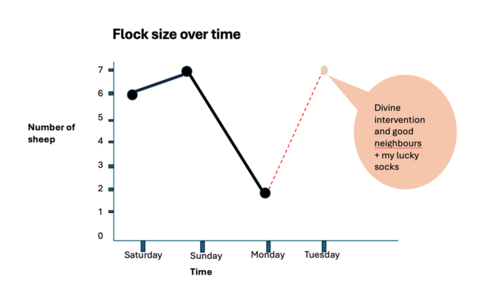

Today is not a good day. It should be. I spent most of the night with a newborn lamb syringing colostrum into it (baby power milk for lambs) and trying to persuade it to suckle. And it worked. Apart from a spot of diarrhoea, we are good to go. Mother and lamb are in their ‘jug’ – a small, enclosed space that encourages bonding and feeding. All is good with the world. But it’s not. I made a rookie mistake. I purposely left the side paddock gate open in the middle of the night so that the rest of the flock – led by Amun Ra, the sweet-tempered young ram (‘Tupp’ where I come from in England) who is more doting than fiercely protective – anyway, so that they might graze the back lawn grass from early morning. Because I knew I was doing to be dead beat. Rookie mistake. They have disappeared. All five of them. If you made a graph of my flock size against time since Saturday it would look something like this:

In my defence, I had just been stung in the eye by a wasp whilst clearing out an old straw pile, and my wife Nikki had just got a concussion (another very long story) and gone to bed. She’s still there. I was dog tired, and I still am, having walked about 1 more mile than the Proclaimers looking for the sheep, which surely counts for something.

Anyway, why am I engaged in this masochistic exercise? Why sheep? Ostensibly because we have a hillside pasture that hasn’t been grazed in 50 years and we need to get it into fettle and find a more ecological way of keeping the willows under control. But it’s also because I am or was English – and although we love it here, I miss beer and pubs (my sister has a little brewery), hedges, black-pudding, kippers, sheep and sheepdogs. In a flight of whimsey and in order to repay my family who had inflicted yet another stray cat on me, I went out one morning and came back with 6 American Blackbelly sheep and a border collie called Jura. And so here we are – or rather were: my heart full of heady dreams of winning a sheep dog trial and my head oblivious to the economics of rearing sheep. And everything was going just fine and dandy until this morning. ****! I’m not sure if I can say that in a SERS blog, but it’s pretty much what I shouted at the top of my lungs when I discovered the mess I had created.

So how does this relate to my work in SERS?

I’m interested in landscape, ecology and political economy – as they relate to sustainability. For a decade I have been working on a project seeking to revive hedgelaying in the Ontario countryside – those carefully laid and constructed hedges that make the patchwork quilt of fields across Britain and Ireland (its basically a hobbit thing). The interesting thing about hedges is that many of them in England are up to 2000-year-old, and there is a style of construction for every county and every kind of farming activity. However, many are much younger and were created by the process of capitalist modernization. Before coal, it was wool production that drove early modern capitalism – in a revolution that would spread out across the entire globe. To facilitate the new commercial-scale sheep farming for profit, the common lands were ‘enclosed’. This means that the peasants were kicked off. The landed gentry eschewed their feudal obligations towards the poor and landless and became driven by the ‘cold calculus’ of the market. The ‘enclosure movement’ started the process that created the modern world. And the mechanism for enclosure was the hedge. The newly ‘liberated’ peasants, no longer tied to the land were forced into the burgeoning industrial cities in godforsaken parishes that no-one had ever heard of (‘Manchester’) and overtime were transformed into wage labourers – or the proletariat, if you’re a Marxist (don’t be one though – not if you are interested in truth). So sheep farming created modernity. But interestingly, it also did it with a new dog. Old English sheep dogs are woolly and stupid. They sit in the flock and bark to ward off wolves. With the extinction of wolves in England, from the 13th century sheep could be grazed extensively over hundreds of square miles across the uplands. In order to gather them in a new breed evolved in the English and Scottish borders (or God’s country as it is known by wiser hobbits). So hedges, extensive sheep farming for profit, the border collie and the landscape of upland Britain -- all tell the same story: what Polanyi called ‘the Great Transformation’ or the emergence of the modern world, warts and all.

Reflecting on this story, it occurs to me that sheep are once again at the forefront of a struggle to transform the modern world all over again, this time in order to address the problem of global sustainability.

The way in which we choose to regulate, transform and even eliminate the livestock industry over the next twenty years intimates two starkly different societal futures informed by equally antipodean political philosophies. Two parallel and mutually incompatible futures for sheep farming in particular, capture a much broader choice about the future of capitalist modernity.

A technocratic global liberalism would represent continuity - albeit in the form of an increasingly authoritarian ecological modernism. This way lies big high tech. corporate agribusiness sustaining only uber-efficient, capital intensive and tightly regulated, large flocks with total supply chain surveillance and traceability – or even the virtual elimination of livestock farming in favour of synthetic protein meat substitutes. The ecological space bought by such economies of scale would allow a simultaneous ‘re-wilding’ of the uplands, bringing not only ecological but also aesthetic benefits, albeit to a constituency of remote, up-market urban professionals and wilderness seekers. Making modernity sustainable is a tall order. But protagonists of Net Zero and ‘total supply chain sustainability management’ seek to achieve it not by reevaluating the ultra-mobile society of individuals. Rather, through a sort of market collectivism, this trajectory is intent on leveraging digital identities, digital currencies, digital health passports, and a punitive social- legal incentive structure to alter behaviour and consumption patterns from the top down. As many have observed, the COVID lockdowns and state/corporate (mis)information management regime were a trial run for this kind of totalizing sustainability through global governance.

By contrast, a post-liberal localism would forgo some of the efficiencies of global trade and comparative advantage. A new proliferation of small-scale, mixed, family farms would take advantage of increased barriers to global trade, supplying a much broader array of sheep-based ‘circular economy’ products for food, clothing, chemical and even construction industries. The former is a materialist, strictly economic vision, lowering costs, delivering quantity and/or substituting new products and materials. The latter vision involves the partial dissolution of the ‘economy’ as such, the re-embedding of some economic activities into broader cultural and religious frames of reference and evaluation. Global liberalism maximises individual freedom, whilst paradoxically and simultaneously increasing the dependence of individuals upon increasingly monolithic states and corporations. Post-liberal individuals would be less constrained by the state, and more by the lattice of mutual obligation associated with the particular cycles of work and cultural activity pertaining to specific places and landscapes. Global liberalism promises a higher standard of living, albeit sustainable according to the metrics of ‘Environmental and Social Governance’ (ESG); whereas post-liberal localism virtually guarantees lower levels of consumption, but possibly higher levels of social cohesion, familial stability, happiness and mental health. Sheep farming with a small ‘c’ refers to the latter trajectory - a species of conservatism which re-tunes the business of making a living to harmonise with what earlier civilisations understood as ‘the natural law’.

My own interest in these two trajectories arises from a single feature of all social-ecological systems which is that social complexity funded by and proportional to the metabolic throughput i.e. the flows of energy and materials, as well as waste products. Complex liberal societies are high energy/throughput configurations. Environmentalists should be cautious in calling for ‘degrowth’ or any significant contraction in the scale of human activities – because less energy, less throughput probably means less complexity in the long run. The same is true of post-liberal localists like me and Kristen (a former student). Any significant shift to small-scale, place-bound more local communities would involve possibly unanticipated losses. For a variety of reasons (which you can ask me about), such configurations may well see rising levels of interpersonal violence and less psychological restraint everyday life. Be careful what you wish for. The great economist Thomas Sowell once observed that there are three questions you should always ask yourself in evaluating some of other proposal:

Compared with what?

‘This or that outcome or proposal is terrible …’ Compared with what? He had in mind, iconoclastic utopian critiques of present arrangements that would rip up social institutions and start again, but on the basis of some counter-factual, utopian assumption about a state of affairs that might or might not be possible at some time in the future.

At what cost?

Usually, political proposals or ideas are presented with the emphasis on one set of clear benefits. Often, they are framed in terms of one over-arching value (e.g. justice, or equal outcomes) but my completely ignore evaluations based on other values (e.g. freedom). People with exactly the same values can disagree fundamentally about politics quite legitimately, simply by weighting those values slightly differently. So it’s important to be really clear about ALL the costs, both short and long term and in relation to all the values or priorities that may be at play.

What’s the evidence?

Everyone talks about ‘evidence-based’ policy, but as JS Mill observed, if you only know your side of the argument, you basically understand nothing about the issue at hand. In order to have all of the relevant evidence, you have to include the kind of evidence from people with whom you disagree – possibly strongly. If you preclude their ‘evidence’ your own is worthless.

These questions apply equally to my own Romantic attachment to small-scale, distributed familial and household-centred forms of economic life, as to the top-down, regulatory vision of global sustainability and the green new deal. If we’re honest, neither trajectory is unproblematic. What do you think?