The Waterloo Record did a piece on the RoboHub on October 29th as part of the coverage around the E7 Grand Opening. Visit their website for the original article.

Pearl Sullivan is standing inside a room where robots will float above the ground thanks to magnetic levitation technology.

As the dean of engineering at the University of Waterloo she is constantly exposed to cutting-edge technology, but the RoboHub takes that to new levels.

It is among the most advanced robotics research hubs in the world and is located on the main floor of Engineering 7 — the latest building for the university's biggest department, which officially opened Monday.

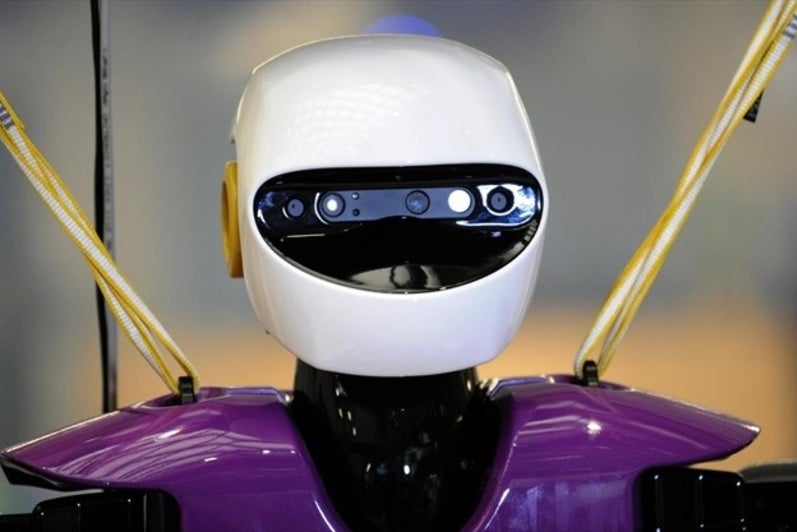

Before the opening celebrations, Sullivan visited the RoboHub. There are cute-looking companion 'bots, drones and a sturdy-looking humanoid-machine that walks and picks up a bottle of water.

"We had a strategic plan to develop the University of Waterloo as a world leader in human-centred intelligent robotics," said Sullivan.

Robots that perform repetitive tasks, such as spot welding the frames of vehicles on a production line, have been around for decades. But robots that work alongside people, that have turning heads, blinking eyes, and that speak and respond to verbal commands are moving into the real worlds of work and play.

"The future is human-centred robotics, which means robots work alongside humans, so they need a soft touch, they need to be able to work and gently tap you," said Sullivan.

UW has a research chair in intelligent robotics that is held by Kerstin Dautenhahn, one of the founders of the field of social robotics. Ottawa will fund her research for seven years. She works on artificial intelligence for robots that teach children with Autism how to read. She also develops robots to help frail seniors with daily tasks.

There are now 45 professors at the university working in different areas of robotics, from driverless vehicles and autonomous systems to wearable technology and social robots. Sullivan wants more collaboration among them.

"So we become leaders in the world for human-centred, soft robotics," she said. "And if you want to be a partner with the world-leading research institutions, you have to be comparable and at least on par with their calibre of research. We're there."

The new building sits near the eastern edge of the main campus. Between Engineering 5 and Engineering 7 is a huge atrium. On the fifth floor is a bridge that joins the two buildings.

It is equipped with sensors that measure the total weight on the span, the direction and velocity of people and objects, and how the structural steel expands and shrinks. The information is displayed on a monitor at one end of the bridge.

Some of the windows in the Engineering 7 also have sensors that measure humidity, temperature, wind pressure and how the changing weather impacts the exterior.

"For certain industries it is important to calculate wind pressure and how wind tunnels get formed around buildings," said Octavian Ciubotariu, the chief technology office for Enable Education in Milton, one of the university's industry partners.

Enable Education provided the sensors and monitors on the bridge and windows. The data will be shared with engineering students.

"Students can get very creative with that kind of stuff," said Ciubotariu.

Engineering 7 was built with help from a long list of supporters. There were donations for $25 million, $12 million and $10 million from anonymous supporters. There was a $5 million donation from David and Linda Cornfield, Carl and Kate Turkstra. In total, the university received $36 million in private donations, and $32.6 million from Ottawa's strategic innovation fund.

"It is an important project not only for Waterloo, but for our country, because research secures our future," said Sullivan.

For Sanjeev Bedi, a professor of mechatronics and mechanical engineering, a building is just a building. Even a new, state-of-the-art structure for teaching and research. He lives for ideas, or immersive design engineering activities.

Bedi oversees two Ideas Clinics, and it is his task to keep students enthusiastic about engineering while they complete foundational courses in math, physics, chemistry and the like. The Ideas Clinic is where they work with their hands on real projects. They work in groups on increasingly complex problems.

One clinic is for mechanical, civil, and chemical engineering students. It also has a machine shop lathes, mills, drill presses, advanced manufacturing machines, 3D printers, a PVC making facility, a sand pit and a water tank. The second clinic is for software-related projects and the Internet of Things.

A glass company approached Bedi about a huge problem. About one per cent of the glass made in the world gets broken during shipping. That is 18 tonnes of broken glass every day, said Bedi.

"That is a lot of glass," said Bedi. "This is an ideal example for the Internet of Things."

The glass company wants UW to make frames with sensors that measure the forces on the panes during shipping. It will collect data that will help in the design of better frames.

"I want engineers who will go out there who make a difference," said Bedi.