Following are my reflections on the final lecture of Prof. Prateep Nayak for INDEV 101. He revisited the case of Chilika Lagoon, which was his point of departure in his first lecture for the Winter Term last January 2018. Prof. Nayak wrapped up the term by asking the class to discuss our chosen development issue and how we propose to address it, given the new insights and knowledge we have gained through the course.

The proliferation of the aquaculture industry and commercial fisheries in the Chilika Lagoon brought about environmental, economic and social changes to which the people dependent on the lagoon had to adapt. As large fisheries and aquaculture took over more and more of the resources in the lagoon, a battle ensued between the villagers and the commercial fisheries, marred with disputes and court cases. The livelihood of the small scale fishers were affected and many were forced into poverty. Skilled fisherman turned labourers in nearby cities in order to feed their families. Even the villagers’ culture and way of life were displaced. Children dropped out of school at alarming rates, and local institutions crumbled. Nonetheless, throughout the political, social and economic turmoil, the decision was made to open an “artificial sea mouth” (Nayak, 2018) which effectively changed the ecosystem. The environmental cost of the changing ecosystem could not be repaid and the culture and livelihoods that were lost could not be rebuilt.

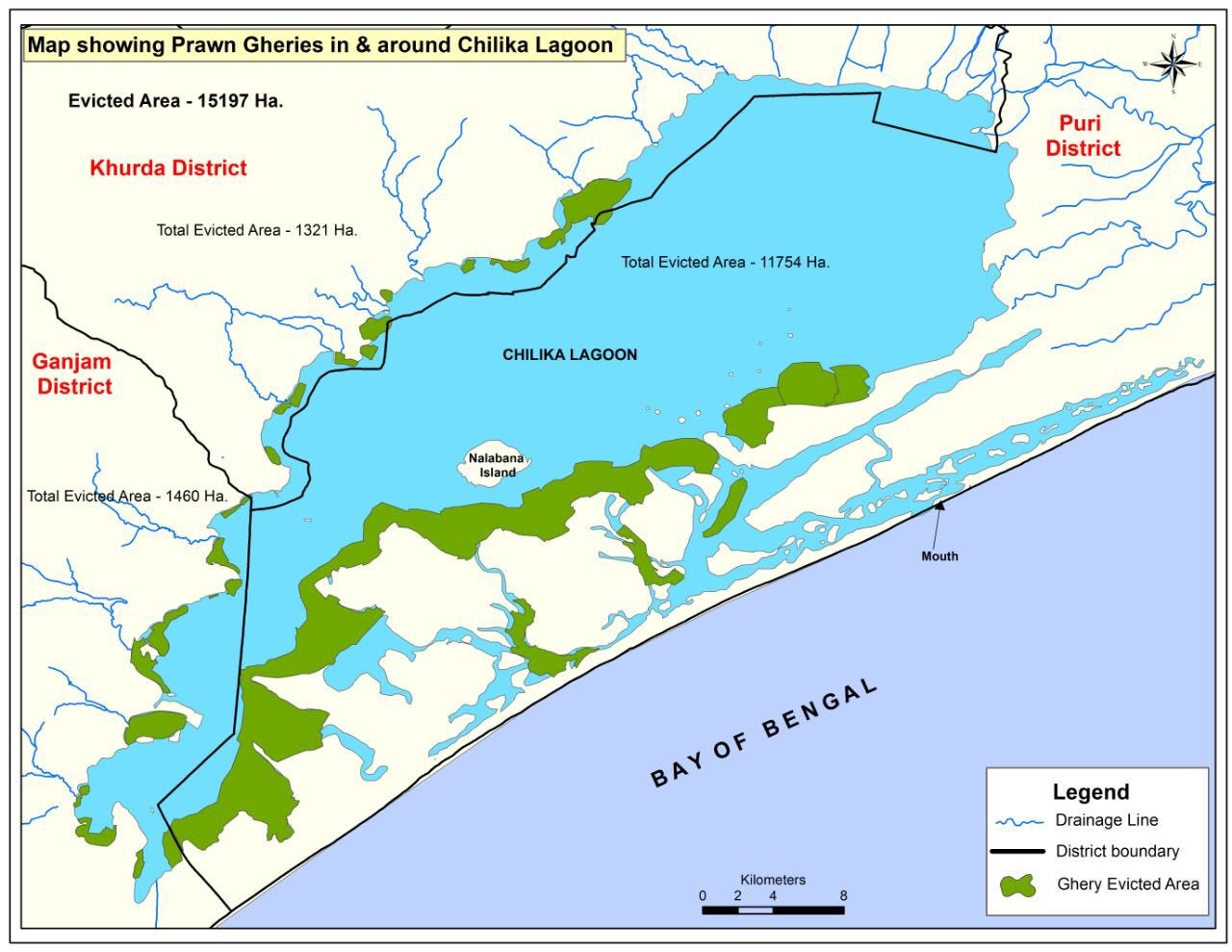

Map showing prawn gherries (pen culture) in and around Chilika lagoon. Photo by Susanta Nanda/Chilika Development Authority.

Source: Mongabay

Opening the artificial sea mouth allowed ocean currents to pass through a space that was naturally blocked by land. Allowing water to pass through caused ocean water to flow freely into the lagoon, tipping the saline balance on a delicate ecosystem. Along with the salty ocean water came sand and unfamiliar creatures such as stingrays and barnacles, further disturbing the lagoon by introducing “invasive” new species and bacteria. Biodiversity in the lagoon was diminishing due to the unsustainable actions of the aquaculture industry and scientists determined that opening the sea mouth would help bring larger fish and more life back into the lake (Sahu et al, 2014). Dredging a new sea mouth saw the increase of larger fish in the lagoon as well as stabilization of plant life. Despite the subsequent benefits of opening the lagoon to the ocean the initial problems remained. The problem of commercial activity was having detrimental effects on the environment and on the lives of the people who were dependent on the lagoon. This fall in fish harvest has been attributed to overfishing, conflict in fisheries and ecological degradations of the lake (Mangla 1989; Patro 1988; Panigrahy 2000). The opening of the artificial sea mouth did not address the greatest threat to the lagoon and the people living around it—the business of aquaculture.

Fisherman casting the net at Chilika Lagoon

Source:Rainwaterharvesting

Through the expansion of the aquaculture industry in the Chilika Lagoon, there was a shift in the use of resources from livelihood to economic profit. This shift put a stress on the small-scale fishermen who lacked formal education and could not take up any other economic activity except fishing. This, in turn, promoted the vicious cycle of poverty that many of the Chilika Lagoon residents faced. Outmigration to neighbuoring towns to work as labourers was resorted to by the villagers to continue to survive. The poor driven away from their land by the rich is a story heard many times before.

Civil action by the people of Chilika Lagoon, and the results thereof, is another story worth telling. The damage to the ecosystem was so great that people began to protest the aquaculture industry. Court cases and protests brought the local resistance to the international stage. As a result, aquaculture was banned by the Supreme Court but enforced several years later.

Restoring the lagoon to what it once was cannot fully be done, although repairing the system to rebuild lives can be done. Restoring the livelihoods of villagers living around the lagoon will require an integrated approach. Social and economic development that allows those who depend on the lagoon for survival must be given priority. Regulations must be enforced to ensure the lagoon ecosystem can thrive with biodiversity. “These (lagoon ecosystems) are the most threatened ecosystems” (Downing et al. 1999) and must be protected from unsustainable and unethical business practices. The pursuit of economic prosperity must not come at the cost of lost livelihoods, cultural practices and delicate ecosystems.

References:

Downing JA, McClain M, Twilley RJ, Melack M, Elser J, Rabalais NN, Lewis WM, Turner RE Jr, Corredor J, Soto D, Ya ́ nˇ ez-Arancibia A, Kopaska JA, Howarth RW (1999) The impact of accelerating land-use change on the N-cycle of tropical aquatic ecosystems: current conditions and projected changes. Biogeo- chemistry 46:109–148

lagoon. (n.d.). Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 10th Edition. Retrieved April 10, 2018 from Dictionary.com

Mangla B (1989) Chilika lake: desilting Asia’s largest brackish water lagoon. Ambio 18(5):298–299

Nayak BK, Acharya BC, Panda UC, Nayak BB, Acharya SK (2004) Variation of water quality in Chilika lake. Indian J Mar Sci 33:164–169.

Panigrahy RC (2000) Chilika lagoon- a sensitive coastal lagoon. J Indian Ocean Stud 7(2&3):222–242.

Panigrahi, S., Acharya, B.C., Panigrahy, R.C. et al. Wetlands Ecol Manage (2007) 15: 113. Anthropogenic impact on water quality of Chilika lagoon RAMSAR site: a statistical approach

Patro SN (1988) Chilika - The Pride of our Wetland Heritage (a state ofthe art report). Orissa Environmental Society, Bhubaneswar.

Sahu, Biraja & Pati, Premalata & C. Panigrahy, R. (2014). Environmental conditions of Chilika Lake during pre and post hydrological intervention: An overview. Journal of Coastal Conservation