On February 2 of 2017, Dr. Mohammad Moniruzzaman visited the first year International Development students to present his research on remittances and food security in the context of Bangladesh. Working with the International Development Research Centre as well as the Canadian government’s research council the title of his presentation runs as “Debt-financed Migration to Consumption Smoothing; Tracing the Link between Migration and Food Security (PDF)”. He provided valuable insights into the topic, as well as in-depth statistics regarding the topic and reasons for the distribution of the data collected. He has a background in Economics and Public Administration, and is now a Postdoctoral Research Associate in migration.

An important aspect of migration and development emphasised by Dr. Moniruzzaman was remittance. Many households with a migrant member depend on this as their main form of income. Remittance is the money sent back home by the migrant member of a family. Through his work in Bangladesh, Dr. Moniruzzaman found that remittance allows families to have more positive outcomes for the welfare of their households. It is either the father or a male member of the family who migrates for work and sends money back home for the family. In most circumstances, the migrants find jobs in the Arab states. Remittance reduces the family’s food insecurity as it provides assured allowance for food expenditures to be prioritized. Additionally, this form of revenue increases purchasing power that is directed towards food resources.

A key finding in Dr Moniruzzaman’s research was that the HDDS (Household Dietary Diversity Score) was higher in female-headed households. Women spend more on ameliorating the quality of diet in their respective households because it “supports intra-household bargaining models.” This means that there is a general agreement happening within the families to spend more on food rather than other resources, further ensuring food security within underdeveloped regions. Increasing their dietary quality also contributes to the likelihood of good and consistent health.

Despite adequate food access being a positive outcome of migration due to remittance, migration also causes resource backwash. Resource backwash results from the fact that in order to have someone migrate, it will cost the family a great amount of resources to do so. Numerous cases show families depleting their limited resources, selling all assets to the point of their own homes as well as loans. To finance the migration process of their family member they must pay for the employment migration agencies service along with their visa, airfare and living cost. Debt amongst the household is a critical component of the migration process as it takes multiple years before the family can pay off their payments while still purchasing the necessities they require on a day to day basis. However, even if this debt-financed migration persists, Dr. Moniruzzaman and his team’s research had found that remittance receiving households are assessed to generally be better off than those who are not, in regards to better health, food security and human development. It does not improve the debt crisis situation but definitely provides positive outcomes.

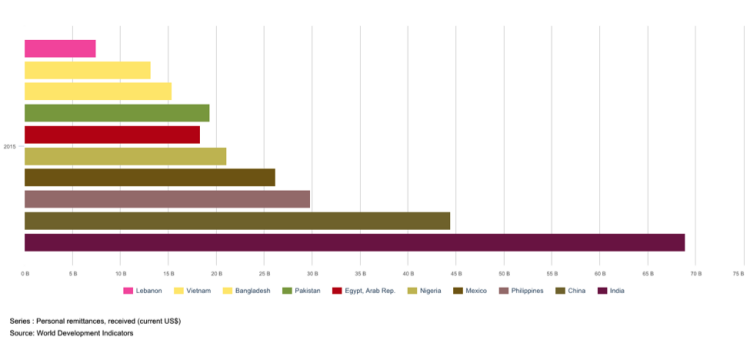

As of 2015, the top ten countries receiving remittances are as follows (in ascending order): Lebanon, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Egypt, Nigeria, Mexico, Philippines, China, and India. Remittances are considered among the top three major contributors to global financial flow. Furthermore, as an underlying issue in migration and development, remittances maintain a general consensus among the public. As discussed by Dr Moniruzzaman, remittances aid in poverty reduction by three to five percent. Secondly, remittances allow for investments, savings, and asset accumulation. Migrants work in other countries mainly because the currency conversions from the host country would provide a higher value when converted back to their country of origin. This would increase the purchasing power of the migrant’s dependents. The third consensus is that remittances provide better educational outcomes and healthcare provisions for the migrant’s dependents as they would be able to afford educational and healthcare costs from the money sent by the migrant.

On the other hand, the link of economic growth and remittances is greatly debated. This is due to the differences in statistical data of different institutions which either shows the positive or negative relationship between economic growth and remittances. According to Dr Moniruzzaman, a positive relationship is depicted in countries such as Mexico, while other countries reveal a negative impact to its economic growth which results in mixed opinions regarding benefits and overall impact of remittances. This sentiment is also applicable in regards to the issue that remittances increase income inequality in a country. Moreover, there is also a ‘moral hazard’ present in remittances as it is considered as free income for people in the family who have not migrated. It is assumed by many that receiving remittances discourages the recipients to participate in the labour force and therein lies the problem

The class was presented with a great display of research into Bangladeshi development and has provided us with a window into the phenomenon of migration. The outcomes in high quality food security through the financial flow of remittance although good causes its fair share of challenges and points towards the role of globalization and how it fuels remittance. Is globalization just a trend to stay or is it a long-term revolution of world economies? If it is, will migration continue to stand as the second top global financial flow? What are the implications of this? More importantly can we ultimately brace ourselves for whatever it is the future holds? In conclusion, we thank Dr. Moniruzzaman for his time, efforts and insight into fueling this conversation for the better of the people, and we hope that he knows he is welcome back.