We are so glad that you are at the University of Waterloo! We have provided some ideas and resources below for designing your degree. Graduate education offers more focus, increased independence, and (usually) more choices for how to design your degree. By recognizing this, you can take charge of your education by becoming a co-designer of your degree, instead of being a ‘good student’. Planning ahead and making goals for yourself can be valuable in enhancing your academic and professional learning, efficiency, and your overall graduate experience.

On this page we focus on identifying your academic milestones, Odyssey plans (a tool you can use), and other things to consider when designing your master’s degree or PhD.

Identifying Academic Milestones

Academic milestones are non-course degree requirements such as specific assessments or activities that you must complete as part of the requirements for your program. Some examples of academic milestones are:

- Academic Integrity Module

- Required training (e.g. WHMIS)

- Internship

- Research proposal

- Data collection / research

- Comprehensive exams (for PhD students)

- Thesis

- Oral thesis defence

Academic milestones/degree requirements vary for each program and are listed in the Graduate Studies Academic Calendar. You can find your program using the Graduate program search. Select “Degree requirements” to scroll down to your specific degree requirements. You can also use Quest to check on your progress and completed milestones by following the instructions for viewing your milestones. Please note that there may be a delay between the time you complete a milestone and when it will appear on Quest and your transcript.

Odyssey Plans

When planning out your degree program, we recommend creating what are called Odyssey plans. We explain what these are below and have prepared two versions of this tool for you to use, depending on your program level:

Master’s Odyssey planning tool (PPTX)

Accessible Master’s Odyssey planning tool (DOCX)

PhD Odyssey planning tool (PPTX)

Accessible PhD Odyssey planning tool (DOCX)

Odyssey plans help us map out possible future paths that we can take. They are both decision-making tools and planning tools.

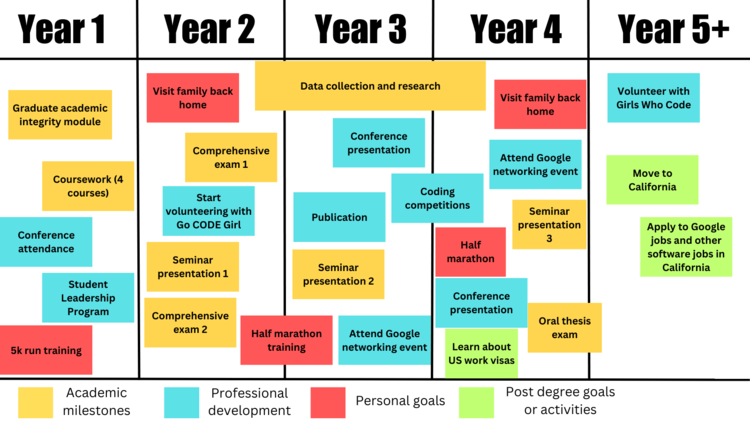

An Odyssey plan involves establishing a blank timeline of your future, at whatever scale you choose (in this case, the full length of your degree program). You then populate this timeline with tasks or goals that you need to complete, creating a calendar of important milestones or actions. In addition to degree-based tasks or goals, you can also include additional personal important tasks and goals (e.g., moving to a different city, participating in a marathon). Below is an example of a PhD Odyssey plan.

What makes Odyssey plans different than other plans is that you don’t just do this once. Instead, you create three “alternate futures,” different versions of the same timeline, with a different tasks and goals. For example, perhaps you’ve considered starting your own company, moving internationally after graduation, or working for the government. By using Odyssey plans, you can think about how you would design your time at UWaterloo differently, depending on your goals. It’s likely that many of your degree related tasks will remain the same – you’ll still take courses and complete your research proposal – but what may change between the plans is the timing and your extra curriculars.

Once you have drafted these “alternate futures,” the Odyssey planning process asks you to take time to reflect on your thoughts and feelings about each of them. How realistic is a plan? How confident are you that you can follow it? How does it make you feel? Asking these and similar questions helps us evaluate our options, deciding on the best path forward using a multitude of considerations.

Why use an Odyssey plan?

There are several benefits to the Odyssey tool over more typical planning approaches. By considering multiple viable alternatives, we avoid tunnel vision, prevent ourselves from fixating on the myth of a single “correct” path that we have to take. Things might also change! This kind of planning helps us be open to opportunities, while also creating structure and intentionality.

What’s next?

Consider trying some of the following:

- Mapping out and reflecting on upcoming plans in your graduate degree

- Seeking feedback on your plans (e.g., from your supervisor)

- Putting your Odyssey plans into action

- Exploring other opportunities on and off campus

Additional Resources

- The Centre for Career Action offers many workshops on exploring career pathways, career interests, and your personality as it relates to careers. Career advisors can also help you form goals.

- The Student Success Office offers workshops and online resources related to planning, time management, and other important skills.

- Get involved with other students outside your lab or department! Engage in more cross campus workshops, get involved with the Graduate Student Association, or engage with an interdisciplinary research institute to start.

- Download our designing your graduate degree (docx) document for more information.