By Tienna Schade

Dr. Murchison “Murch” Callender’s career journey has been marked with victorious highs and discouraging lows. As one of the first Black faculty members at the University of Waterloo, much less the School of Optometry and Vision Science, he persevered in the face of racial inequity and overcame numerous barriers to become a highly respected expert in contact lenses.

Born in Trinidad and Tobago, Callender knew his strengths were in the biological sciences. After high school, to save money, he worked as a research assistant at an oil company in Trinidad before entering a Bachelor of Science program at George William University (now Concordia) in Montreal. Subsequently, Callender went on to McGill University to research diabetes and the outcomes of insulin deprivation.

Callender recalls two instances that ignited his interest in vision and suggested he should pursue a career in optometry. Insulin deprivation led to blindness in his animal models, which fascinated him. Not long after this realization, a young woman named Chloe came to visit her cousin in Montreal, who happened to be Callender’s roommate. Chloe later became Callender’s wife.

“She was wearing rigid contact lenses, but I noticed her eyes were red and I began questioning why,” he says. “This was the second indication that told me maybe I should do something with the eyes.”

Callender applied to the College of Optometry in Toronto and was accepted. He started his degree there and moved to Waterloo after the College became part of the University. He graduated in 1968 as part of the first class to convocate from the new location.

Dr. Callender in the early 2000s

Of the 24 graduates, only two did not receive interviews to associate with a practitioner. Callender was one of them. He identifies this as one of his first subtle experiences of discrimination within optometry. Eventually, he interviewed with a practitioner in Southern Ontario but was told he would not fit in with the community – another subtle experience with discrimination.

“That was a shock to me,” he says. “I thought I would bring a lot to that community – I had the most up-to-date education in optometry and research experience from my time at McGill – but I shrugged it off and knew something else would turn up.”

While he was searching for private practices to join, Callender held a part-time position at the School of Optometry and Vision Science – but he was working full time hours and received no benefits from the University. Yet another inhibiting encounter with discrimination.

A year later, a young professor was hired at the School and saw Callender’s potential. The young man played a key role in instigating the School to give Callender a full-time position as a lecturer with benefits.

As a full-fledged faculty member, Callender contributed extensively to the School and the field of optometry. He spearheaded an overhaul of the contact lens program so students would be trained in a more clinical and evidence-based manner.

“Before, contact lens teaching was more of an art than a science,” he says.

He also designed forms for quantificational recording of patient information so researchers could retrospectively find information easily. His designs were adopted by many other schools and practitioners across North America. At the time, they were paper based, but they were modified for the software that was developed by a University of Waterloo graduate: Visual Eyes. VisualEyes is the digital patient information system hundreds of clinics across Canada, including the Waterloo School of Optometry clinics, use today.

Alongside his teaching duties, Callender kept up with contact lens research. He was one of the first clinicians in Canada to investigate and introduce the rudimentary hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) material used for soft contact lenses to the country. Companies from the United States and Japan came to him for his expertise.

To move up the ranks of faculty positions, Callender completed a master's degree in the biology department. He also started the Contact Lens Journal, now renamed to the Contact Lens Compendium, to provide Canadian practitioners with up-to-date information in the field of contact lenses. Today, it’s available online as a worldwide publication.

In 1988, he became a founding member of the Centre for Contact Lens Research (CCLR), now known as the Centre for Ocular Research & Education (CORE). Over the years, CORE has become an established global leader in the contact lens space and has been involved with some of the most meaningful advancements in the history of contact lenses.

For over 45 years of his career, Callender travelled to Jamaica twice a year with groups of fourth-year optometry students to provide voluntary eye care services to underprivileged people. Long after the School ceased to provide financial support due to budget cuts, Callender and his students continued the mission by fundraising and covering costs out –of- pocket. As a result, over 30,000 patients received eye care.

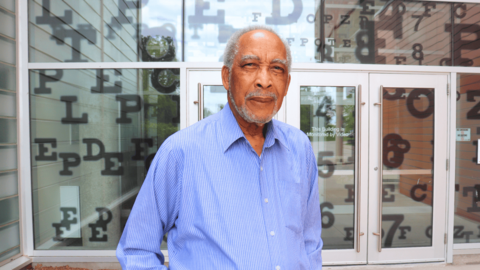

August 2024 - Dr Callender's retirement celebration

Callender retired from his full-time duties in 1996, and up until very recently, remained actively involved with the school as an adjunct professor and part-time clinical supervisor. When asked why he’s stuck around for so long, he has a few main reasons. Firstly, because he finds immense satisfaction in seeing patients and treating those who’ve returned for follow-up care for decades. He also loves sharing knowledge with eager students, and in 2021, after the passing of Dr. Gina Sorbara, former head of the Contact Lens Clinic, Callender wanted to help maintain the quality and standards of care for students and patients alike.

Nowadays, much of his time is spent caring for his wife, Chloe, who has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The extent of his involvement with the School is dependent on her needs, so he has decided to not return as a part-time supervisor, but he still plans to remain in touch.

“I am always available for the people at the School,” he says. “And I will continue to be there, as long as I can breathe life into my body.”