Dana Porter Library, first floor

University of Waterloo Library

Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1

519-888-4567 x42619 or x42445

In 1943, with the Second World War raging, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce began (rather optimistically) to plan for the coming peace, and they invited the Waterloo and Kitchener Boards of Trade to participate in an experimental fact-finding survey of Waterloo County (now Waterloo Region), to determine "economic facts about the past and present and the expectations of the future in their district".1

During the war, although there was nearly full employment and people had a lot of money, nearly all manufacturing had been converted to military purposes and consumer goods were scarce; there was nothing for people to spend their money on. The Chamber of Commerce was interested in what goods people intended to buy, so that industry could be properly retooled to produce what people wanted, and so that there would be jobs for returning servicemen and servicewomen.

The plan was to release the findings from and procedures used for the Kitchener-Waterloo Survey, so that other boards of trade could conduct their own surveys; however, no other surveys were ever undertaken.

1 Kitchener-Waterloo Survey, foreword.

Kitchener-Waterloo Survey: A Fact-Finding Survey for Post-War Planning. Part I. The Findings. The Canadian Chamber of Commerce 1944. [Stamped, bottom right hand corner: From Kitchener Board of Trade]

The special problems facing farmers during the war.

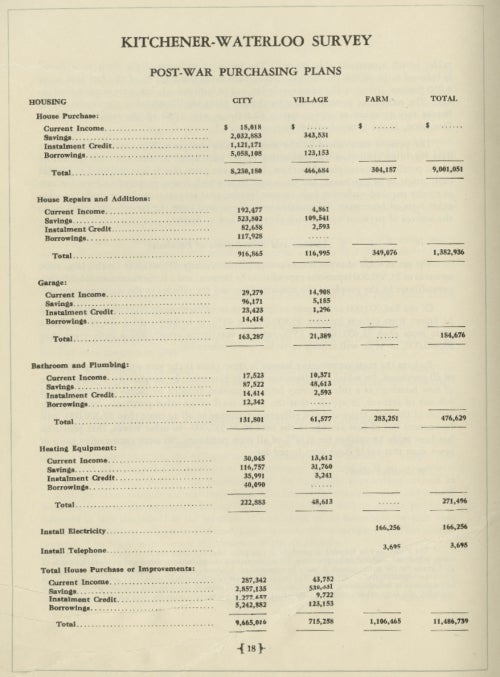

Farmers were not asked the source of the funds they intended to spend. Note the money required to install electricity and telephones on farms. I also find interesting the comparative levels of borrowing and installment credit between city and village dwellers.

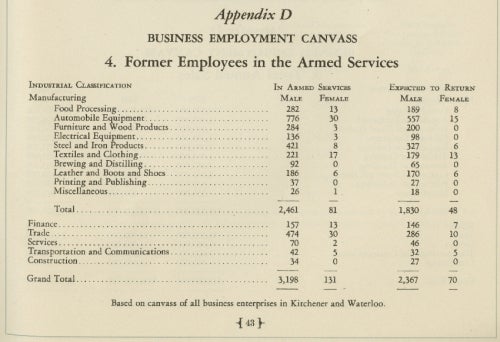

This small chart buried on page 43 appears to be the only acknowledgement in the entire survey that soldiers were dying overseas. Given that the war was still in full swing, I'd be curious to see how they came up with their "expected to return" numbers. Are these the people who upon enlisting told their bosses that they intended to return to their jobs? Are they the people still alive as of the completion of the survey? Are they the subject of some complex actuarial calculation?

Next post: New exhibit : 16 days of activism against gender violence

Previous post: Anti-suffrage bud vase