Dana Porter Library, first floor

University of Waterloo Library

Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1

519-888-4567 x42619 or x42445

The Case of Valentine Shortis

Back in November, I began reading The Complete Tales of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle, and although I’m not the biggest fan, it came in handy with this. No, it didn’t inspire me to write about everyone’s favourite cocaine addict, but it did remind me that when it comes to murder stories, I much prefer nonfiction to fiction, which prompted me to look for other murder-related books in our catalogue. This led me to a book called The Case of Valentine Shortis: A True Story of Crime and Politics in Canada by Martin Friedland (call number: G9256). It’s exactly what the title says: a terrible murder that had lasting effects on not only the seemingly apathetic killer and the families of his unfortunate victims, but the Canadian government itself. I thought it would be an interesting way to learn more about Canada’s history, while reading about a true murder story.

Back in November, I began reading The Complete Tales of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle, and although I’m not the biggest fan, it came in handy with this. No, it didn’t inspire me to write about everyone’s favourite cocaine addict, but it did remind me that when it comes to murder stories, I much prefer nonfiction to fiction, which prompted me to look for other murder-related books in our catalogue. This led me to a book called The Case of Valentine Shortis: A True Story of Crime and Politics in Canada by Martin Friedland (call number: G9256). It’s exactly what the title says: a terrible murder that had lasting effects on not only the seemingly apathetic killer and the families of his unfortunate victims, but the Canadian government itself. I thought it would be an interesting way to learn more about Canada’s history, while reading about a true murder story.

Politics

At the time of the murders committed by Shortis in 1895, the Prime Minister was Mackenzie Bowell of the Conservative Party and in opposition was the Liberal Party led by Wilfrid Laurier. Meanwhile, in Manitoba there was the issue of having separate schools based on religion (i.e. the Manitoba Schools Question); and in Ottawa, Bowell’s cabinet was losing faith in him. Bowell was not elected into his position. After the untimely death of Prime Minister John Thompson, Governor General Aberdeen (who used to be Lord Lieutenant of Ireland), put Bowell into power because he did not trust Charles Tupper to be the Prime Minister.

Fun fact: Lady Aberdeen, wife of the Governor General, was the first President of the National Council of Women of Canada. In fact, our Rare Book Room has a Lady Aberdeen Library on the History of Women donated by the Council in 1967, also making this year the 50th anniversary of the collection!

Fun fact: Lady Aberdeen, wife of the Governor General, was the first President of the National Council of Women of Canada. In fact, our Rare Book Room has a Lady Aberdeen Library on the History of Women donated by the Council in 1967, also making this year the 50th anniversary of the collection!

"Lord and Lady Aberdeen, 1898", (Friedland 132).

Case Overview

At the time, Shortis’ case was the longest tried in a Canadian court; it lasted twenty-nine days, largely because all evidence, testimonies, et cetera had to be said in both English and French (as Shortis was tried in Quebec).

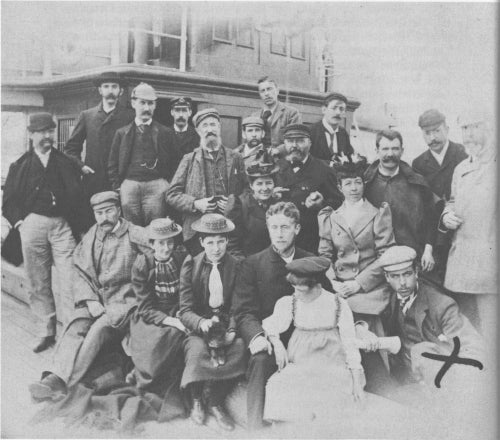

"Valentine Shortis (marked with an ‘X’) on board the S.S. Laurentian, coming to Canada [from Ireland], September 1893", (xii Preface).

A brief summary of the case:

- On March 1st, 1895, in Valleyfield, Quebec, Valentine Shortis shot and murdered two men, a third miraculously survived a shot to the head, and two others escaped harm by hiding in a vault. The murders took place at the cotton mill office, where Shortis used to work, while the aforementioned men were preparing pay packets. Although still uncertain, it was speculated that the murders were a result of a robbery gone wrong.

- During the trial, Shortis pleaded not guilty and the defence argued that he was insane. They found four psychiatrists as expert witnesses to support their case.

- The Crown argued that he was not insane and completely aware of his actions; the murders were premeditated (i.e. first-degree murder).

- On November 4th, 1895, the jury pronounced Shortis guilty and Judge Mathieu sentenced him to death; he was to be hanged on January 3rd, 1896.

- It never happened.

"[Top-]left: Donald MacMaster, QC, Crown counsel… [Top-]right: J.N. Greenshields, QC, defence counsel", (16).

Bottom-left: "Mr Justice Michel Mathieu", (88). Bottom-right: "Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper, March 1895", (118).

Commutation

Henri St Pierre, a member of the defence, sought to ask the Minister of Justice, Sir Hibbert (bottom-right in image above), son of Charles Tupper who would later become Prime Minister, for a commutation,  i.e. to reduce the sentence of death to life in prison. This prompted much correspondence between Sir Hibbert and members of both Canadian and Irish society, one of whom was Lady Aberdeen. She wrote a letter to Hibbert about how she “cannot help hoping that you will in any case recommend that the sentence be commuted to life imprisonment” (130).

i.e. to reduce the sentence of death to life in prison. This prompted much correspondence between Sir Hibbert and members of both Canadian and Irish society, one of whom was Lady Aberdeen. She wrote a letter to Hibbert about how she “cannot help hoping that you will in any case recommend that the sentence be commuted to life imprisonment” (130).

"The Cabinet Room, East Block, Parliament Buildings, sometime after 1886", (146).

Eventually, there was a cabinet meeting to vote on whether or not Shortis’ sentence should be commuted. On Christmas eve, with an even split (five to five) for both commutation and hanging, the cabinet left the decision to Governor General Aberdeen, who sided with commutation. However, the cabinet met again (including two members who weren’t present before) and had another vote; the results were seven to five in favour of hanging. But, that was not the end of it. Another vote was held on December 30th in light of information suggesting that Shortis’ mother, a wealthy woman, was trying to bribe senior government officials to help with her son’s commutation. Lady Aberdeen asked to meet with Sir Hibbert the morning of the vote. Third time’s the charm, right? Apparently not. A fourth meeting was set with another evenly split vote (six to six), prompting Aberdeen to make a final overruling decision of commutation to life imprisonment.

Aftermath

There was speculation that the deadlock in cabinet concerning the Shortis case was another example of Bowell’s poor leadership, along with his lack of decision concerning the Manitoba Schools Question. The commutation also magnified the feeling of discrimination between the English and the French, as “Shortis, an Englishman, was not hung, while Riel, a Frenchman [convicted of treason in 1885] was” (The Montreal Gazette, as cited in Friedland 182). Liberals, such as Laurier, were using the popular opinion that Shortis should have been hanged as a campaign ploy for the upcoming election. Laurier argued that the commutation of Shortis shouldn’t have happened; it undermined the the jury and Judge Mathieu’s decision. Bowell had also agreed with the decision of Judge Mathieu in the first cabinet vote, but he was likely also the one to suggest that Lord Aberdeen be the tie-breaker.

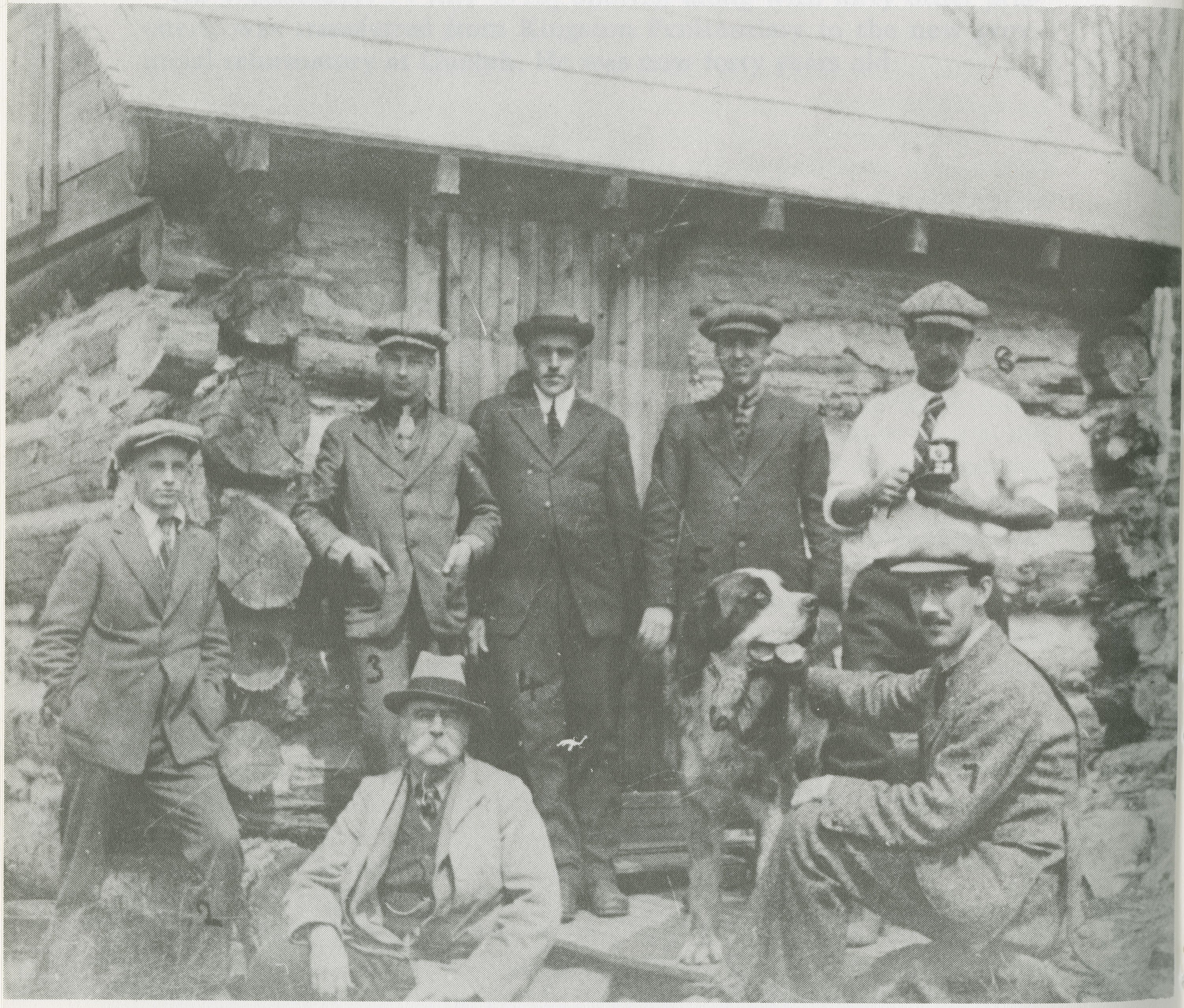

"A picture of Shortis (in the back row on the right, labelled 8) and his dog, with… other officials [from Burwash]" (244).

Nevertheless, Bowell ended up resigning on April 27th, 1886, and Aberdeen, against his personal feelings, made Tupper Prime Minister. His tenure lasted all of two months because Laurier won the election of 1886 with great support from Quebec, where the Shortis case was an especially important issue. In 1915, Shortis was transferred from Kingston to Guelph to Burwash Industrial Farm (for about four years), where he was given many freedoms, including a pet dog. In 1937, after many years of petitioning, at sixty-two years old Shortis was granted ticket of leave (similar to today’s parole). On April 30th, 1941, Shortis died of a heart attack.

Previous post: Volleyball practice, March 7th 1973

Next Post: Murder in the Archives (pt. 2/2)