—

—

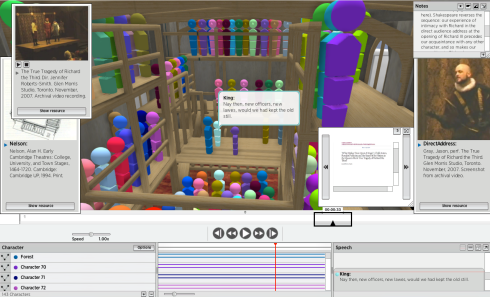

The goal is that one day the program will be capable enough that stage managers will be able to use it as digital prompt book, directors and designers as a digital maquette…

—

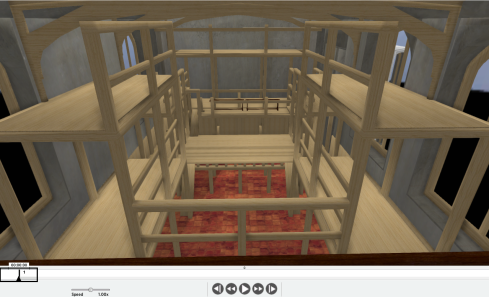

Virtual maquette of UWaterloo’s 2008 production of Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare, Set Design by Bill Chesney.

—

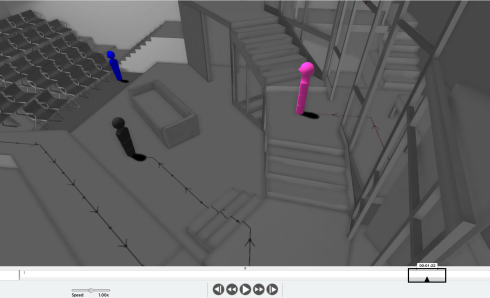

…actors as an aid in remember blocking or movement notes…

—

Character paths in Tarragon Theatre’s 1984 production of Judith Thomson’s White Biting Dog, Set Design by Sue LePage.

—

…scholars as a means of hermeneutic exploration or historical recreation and archivists as a means of historical record…

—

—

Now, as I’ve mentioned before, in theatre nothing goes to waste. As an actor, all I have is my lived experience to bring to the table when beginning work on a show. And so it was with SET. As a member of the team I was able to call upon my theatrical knowledge as a professional actor and magician, my technical knowledge as a CAD Designer (this has been my continual role in the project, modelling virtual theatrical spaces and sets such as the ones shown above), my experience as a former Quality Assurance Analyst testing apps for a living and, yes, even my love of video games.

Why video games?

In brief, the earlier versions of SET were hallmarks of inefficiency. As I was the one QA-ing all of the builds, I had intimate knowledge of their shortcomings and was not hesitant to share them with the team. In one meeting in particular at the end of 2011, the meeting that set me off on the path that brings me here now, I explained to Dr. Roberts-Smith the faults of the current system and asked her what her ideal system would look like or accomplish in terms of user efficiency. Her words were that it should be able to “work as fast as I can think”. From this it was clear to me that video games were the next logical step in the progression of our research because, having played video games for as long as I remember (I’m talking back when they came on 5 1/4″ floppies and Oregon Trail and Kid Pix were things people did in the Computer Lab regularly) I am well acquainted with the fact that in a video game user efficiency is not simply a question of a task being complete or incomplete; it’s a matter of virtual life or death.

—

—

It was then I began a literature review of both video games as well as systems analogous to our own focusing on user efficiency and interface design as they pertained to user purpose. This was a 3-month process that involved examining everything from Mass Effect 2 to StarCraft 2 to dabbling in pre-visualization software such as Moviestorm and even simulation programs like Second Life, and writing reports on my findings. Based on these findings as well as user studies conducted since then we are currently in the process of redesigning the interface from the ground up in preparation for what will be the third version of the program.

But this is all, of course, apropos of the titular cusp. Through one sort of serendipitous event after another I have now had the opportunity to explore the medium of video games for the better part of 2 years. It hasn’t been a cursory glance either. I have had to write detailed reports (through various lenses) on games ranging from Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? to Super Scribblenauts. Needless to say, having grown up with the medium always at my fingertips, this has been quite a pleasurable experience for me. If anybody asks me what I do when I’m not being an artist I can say that I am paid to know things, specifically things about video games and the video game industry. And, as I mentioned in the excerpt from my book in my last post, these things that I’m supposed to know can’t help but influence all other aspects of my life. That’s just what the things you care about do: they leave a trace to be felt in the fibres of every shirt and the handle of every mug.

I have also had the opportunity to ask serious questions about the medium itself.

I recently became involved (again through serendipitous events) in the Gamifying Shakespeare Project, which is a project helmed by Dr. Randall and the Games Institute, in association with the University of Waterloo and Industry Corp., a entertainment design company based out of Kitchener, ON, and the Stratford Festival of Canada, where I’m acting this season in The Three Musketeers (come see the show). The aim of the project is multi-faceted: on the commercial side, the Stratford Festival’s aim is to entice a younger demographic to patronize the festival through the digitization of the works of William Shakespeare and their productions thereof in the form of Shakespearean games/apps designed with that particular audience in mind; on the academic side, our aim is to utilize said digitization as a pedagogical tool, that is, to understand and implement mechanisms that teach this younger demographic about Shakespeare, his works, and the Stratford Festival itself, through the medium of video games.

We are currently working on our first app, Staging Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet, which coincides with the running of the Stratford Festival’s flagship show this season, Romeo and Juliet. Within the game itself, the user plays the role of director and is in charge of staging four major scenes from Romeo and Juliet on each of Stratford’s four venues. Users can then upload their scenes for rating/criticism from other users as well as rate/critique other users’ scenes themselves.

My role in the project has been two-tiered: on one level, as a researcher, I provide contextual research on current systems that incorporate some aspect of either Shakespeare pedagogy or even simply interaction with Shakespearean content, whether it’s characters from his plays, the plays themselves, or even the man himself. On another level, as game designer, I contribute to the conceptualization and design of games in progress. So, for example, on the Staging Shakespeare app I was in charge of designing, among other things, the achievement system.

Engaging in these roles on this project has been a rewarding experience for me because it has brought me to a rather interesting question, one that relates startlingly well to the art of magic. You see, while much of game-related academia is concerned with the meaning of our interactions within the medium of video games, I come at the medium first as an artist and then as an academic. While I am certainly interested in the meaning of our interactions within the medium of video games I believe the far more interesting topic to be the manner in which a video game is architected or structured not only for our interactions, but also as a cohesive whole. Now that we have created Staging Shakespeare, we are realizing that, as David Cage, the CEO of Quantic Dream and creator of Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls (discussed below), alludes to in his keynote speech at the 2013 D.I.C.E. Summit, what we have actually done is created a virtual container. We’ve created a system in which, while we are able to change the content and tweak the mechanisms for interaction with that content, nothing actually changes. In the same way that Modern Warfare 3…

—

—

…is actually no different from Bioshock: Infinite…

—

—

…save for its settings, plot points, and weapons, Staging Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet will be essentially no different from Staging Shakespeare: King Lear save the user will be responsible for staging key events in King Lear and not Romeo and Juliet. So the question then becomes, well, if our intent is to introduce users to Romeo and Juliet through the medium of games then what is the true Romeo and Juliet game? What is the true King Lear game? That is, what is the system that is architected in such a way that it could not convey any content but King Lear, the system that is architected not around the events of King Lear, but through them?

This is the shared cusp.

In these 2 years I have begun to notice a startling similarity between the art of magic and current (and next) generation video games: the transition from a technical medium to an aesthetic one. What do I mean by an aesthetic medium? I am speaking about a medium in which the work is constructed not around its elements, but through them, where the technique that serves as its foundation is not barren soil, existing so that it may simply exist, but fertile soil from which individual works of art may draw their nutrients and grow to their ripened best. An aesthetic medium is one in which sound is not simply the marvelous oscillation of air currents at various amplitudes, but the progression of one specific sound to the next for the purposes of conveying something else entirely. Indeed, within this progression, this structure-like-a-language, this system of signs, the creators communicate something to us, some thing, and we, the interpreters of these sonic signs, decipher it and extract what we may.

Now, it goes without saying that long before the advent of 3-Dimensionality, long before sprawling landscapes and intricate control schemes, games have had the power to tell us compelling stories and make us feel the whole gamut of human emotion. The greatest game I’ve ever played is Final Fantasy 3 (Final Fantasy 6 in Japan), not because of its revolutionary graphics or game mechanics (it was relatively old hat at the time), but because of its story. Anybody who has woken up on this beach…

—

—

…knows the heartache and horror of Kefka, the game’s central antagonist, shattering the entire world and sending every member of your group to its furthest corners. I was having dreams about floating islands long after I completed the game.

Video games didn’t start there though. It took time. Video games began along the lines of Pong: mindless tasks of competition with either another player or the artificial intelligence programmed into the system itself. I’m sure that developers weren’t too concerned either. They were just happy they created a functioning, purposeful system, much like the inventor of the guitar was probably just happy his/her fever dream of wood and strings made pleasant sounds. However, just as with 3-D Cinematography (a gimmick that is rarely used to serve a purpose other than to assert itself as being used), the advent of 3-Dimensionality in video games resulted in the regression of the medium back to its original form. It was no longer about story. It was no longer about affect. For years now developers and consumers have been concerned, to a fault, with simply creating more expansive and breathtaking environments and more realistic cinematics and avatars, as if those were the key ingredients to the creation a meaningful work. And sure, these worlds are a far cry from the void that acted as the backdrop for the digital paddles of Pong, but the vast majority of them involve no less an act of mindless engagement.

To this day video games are still by and large, as Slavoj Žižek puts it, liberation via mechanical ritual, that is, a kind of vacuous liberation in which we are able to rest our life responsibilities on the shoulders of an Other that, for a time, regulates the process in which we participate thus setting our minds free to roam since we are know we are not actually involved. I don’t play Modern Warfare 3 because it’s virtual Dostoevsky making me question my very existence in the world. I play it because for 10 minutes at a time I don’t have to focus on paying bills. I can just focus on the task of winning, which in this case means gunning other users down sometimes en masse.

The majority of this year’s E3 conference (the Superbowl of the gaming industry) was spent either attempting to resurrect the success of originals (surprise surprise, there’s another Assassin’s Creed, even though many people, myself included, just want to beg Ubisoft, the game’s publisher/developer, to let the series die a peaceful death) or show off expansive universes that would require another lifetime to explore fully (The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt won IGN’s People’s Choice Award in part for this reason) or brandish the revolutionary technical ability to level whole skyscrapers or have somebody play with you via their tablet (Battlefield 4, The Division, etc.).

—

—

Is it necessary to point out the similarities between the technical prowess toted by these developers and that toted by magicians? We put the emphasis on our technique (necessarily so, read the book to find out why), on our technical ability, and on the hardware that supports that technique, but in the end nothing actually changes. Indeed, in the same way that Modern Warfare 3 is no different from Battlefield 4 shown above, this cup and ball routine is no different from this “absurdist” cup and ball routine (a misnomer if I ever heard one) save for the cups and the balls and the guy wielding them. The routine is the same: a ball vanishes and reappears in a cup (the repetition of which is intrinsically absurd regardless of whether you’re 5 years old and doing it with dixie cups in your kitchen for your mom or 50 years old and doing it with cups made of rubies in a palace for a sultan). The end. In Modern Warfare 3 you play Guy 1 wielding Gun A hunting down Terrorist Cell X and in Battlefield 4 you play Guy 2 wielding Gun B hunting down Terrorist Cell Y. The end.

Snarl all you like, but in the end nothing grows from barren soil.

But thankfully there was some form of relief to be found in the conference and in the days that followed. A triptych of games have caught my attention because something remarkable is growing from them and I can see technique being aesthetized. I am speaking of: Naughty Dog’s “Game of the Year” contender The Last of Us, Quantic Dream’s Beyond: Two Souls, and Jonathan Blow’s The Witness. I will touch on each in brief as they themselves are not the primary focus, but rather how they each speak directly to my work in the art of magic.

The Last of Us is a story that follows protagonists Joel and Ellie as they travel across post-apocalyptic United States. A fungus known as Cordyceps has evolved to target humans and has essentially wiped us all out. If you watch the video I just linked to you’ll see that it’s a pretty horrific way to die. What’s left of humanity is dispersed and cities still stand as either military dictatorships or dens of thieves and murderers. IGN was right in calling it the video game analog to Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road”, an unsettling rumination of the depression and the tiniest of slivers of hope in a post-apocalyptic world as seen through the eyes of a father and his son.

—

—

It goes without saying that the game is a technical feat and incredibly immersive. I myself have lost track of time on more than a few occasions playing the game. And I could go into all of the ways in which it achieves a level of immersion rarely seen in video games (automatic toggling of the sparse HUD, contextual action, limited inventory, real-time use of inventory, startlingly intelligent AI that is alerted if you so much as hit a stray paint can whilst sneaking up on them and will beg for their lives on certain occasions, etc.) but there is one element in particular that is the veritable icing on the immersive cake and it probably the least impressive given the scope of everything I’ve just mentioned. However, once seen in the light of the other two panels of the triptych you’ll understand its value.

There are moments in the game, as in any other, in which you must interact with an object in the environment, say, a door. To interact with the door you must hit a certain button: triangle on the PS3. Simple, yes? Yes. Until you arrive at one of the doors that require additional action to open them. You are not told what additional action to make. You are not told what button to press or which direction to go. You as the player must ignore every technical aspect of the game itself (the entire interface really) and, indeed, everything video games have taught you in the past (they tend not to leave their players hanging for fear of being turned off abruptly), and look directly at the situation within the game environment in order to glean what you are supposed to do.

I reached a particularly heavy door. I pressed triangle to open it just as the HUD prompted me to. The game recognized the input and Joel pressed his hands against it. And then I waited. And waited. But he didn’t open the door. The avatars were still moving so I knew the game wasn’t frozen. I couldn’t understand what I was supposed to do. It was a moment of white light confusion because it went against everything I had been taught. There should be a prompt. There should be a notification. There should be an alert of some kind. If Microsoft Word told me I could Save a file, but never gave me a menu option for Save and instead forced me find the shortcut key (Cmd + S) I would throw Microsoft Word in the trash without a second thought. So I sat there for a moment or two watching the static scene, Joel and the door, resisting the urge to throw the game away. But then I looked at the position of Joel’s body and saw that his hands were both facing the same direction, as mine would be if I were to attempt to push open a heavy door. (Yes, that was my actual thought process.) I then shifted the analog stick on the controller in that direction and lo he began to slowly slide open the door. I had to keep the stick pointed in that direction until the door was fully opened.

This mechanic is taken to its penultimate degree in the second panel of the triptych, but before we move there I just want to point out: what better way to reinforce a game in which uncertainty and apprehension reign supreme than to create a game mechanic, a way of interacting with the environment, that quite literally leaves the user uncertain and apprehensive as to how to proceed through that world. This is the aesthetization of the technical at its finest.

Now, Beyond: Two Souls is an epic tale which follows the protagonist Jodie Holmes from the ages of 8 to 23 and chronicles her attempts to understand why she is connected to a spiritual entity named Aiden. David Cage, writer and director of the game, has been forthright about his attempts to create an “invisible” interface, that is, an interface in which the player, much like in The Last of Us, is not explicitly prompted to do anything and must look directly at the environment itself for the answers. This mechanic reaches its maturest point during the action sequences in which Jodie is being attacked by one of many assailants that will be attacking her throughout her life (there are more than a few).

—

—

Once the player learns how the game works (there is a tutorial involved because the game is so drastically unlike any other video game that the player must be taught the mechanics in order to have any chance of surviving the world itself) they are left to their devices. And when I say left, I mean utterly abandoned. The action sequences, as in the one shown above, are constructed in such a way that the player must intuit the character’s intentions behind their movement in order to complete it. So in the image above, you can see that Jodie wants to kick out her assailant’s knee. Her leg is moving in the left direction therefore the player must shift the analog stick to the left in order to complete the kick. That’s it. That’s all you get. The game doesn’t even pause to give you time to think. It slows down a bit, but that’s about it. If you are not completely in tune with the action of the sequence then eventually, sometimes not all at once, sometimes one knife stab at a time, you are going to die.

Again, a clear cut aesthetization of the technical. What better way to proffer a game in which empathy is the central aim than to create a game mechanic in which the player must ask themselves time and time again “What would I do in this situation?” Indeed, with the advent of this kind of invisible interface Beyond: Two Souls reverberates with a simple question: Are you listening? The game is trying to tell you something and it is not through anything extrinsic to the game itself, not through the words of its creators or the marvels of its interface, but through the intrinsic elements of the story itself: its characters and their interactions with one another as well as their environments. And while the whole game isn’t structured invisibly, it is certainly an excellent precursor to…

Developed by Jonathon Blow (the creator of the indie-hit Braid), The Witness allows you to play an unnamed character traversing across an open-world island in first-person view solving puzzles. Seems pretty standard so far. There are plenty of games that strand you on an open-world island (Far Cry 3, e.g.). But what’s really interesting about the game is that there is no HUD, no tutorials, no prompts, no overt story, no combat, not a single letter of text, nothing. The interface is entirely invisible.

—

—

So how does the player know what to do, where to go, etc.? As mentioned, the player must solve puzzles to “progress” through the island. But the player is never taught how to solve the puzzles. They simply encounter them one after another with each consecutive puzzle offering an additional, increasingly difficult variation on an old one already solved. Pardon the wordplay, but in this respect this game is an island apart from every other game introduced at this year’s E3 conference. While many developers would never dream of stranding the player in a world without any help or hint whatsoever, Blow revels in it, forcing the player to focus not on what he as a developer is telling them about the world, but what the world itself has to say.

And it has a lot to say.

Indeed, everything the player needs to solve the puzzles and understand why they are doing it is written into the game world itself. While some puzzles require a simple action like tracing a specific path, more complex puzzles require the player to spot the patterns in the apples trees that adorn the meadow or see the wall of a broken down house from a different vantage point in order to find the solution. And each solution is a path that allows that player move forward and discover more of the island.

This is what I’m searching for in the art of magic. This is why I wrote this post. This is why I wrote this entire blog. This is why I wrote a book and do work that I myself don’t even understand half of the time. I am searching for a world in which nothing extrinsic to the system of signs generated within the medium itself provides meaning. I am searching for a magic in which everything the audience needs – the message, the meaning – is written into the magic itself. Not in my words. Not in my music. Not in my video projections. Not in my lighting. Not in my costume. I am searching for an island in the world of magic in which meaning is an intrinsic construction, something generated through the perceived connection between the elements that comprise the island itself.

In my book I ask my readers to imagine a dancer walking on to the stage and beginning his or her routine, which is then accompanied by closed-captioned subtitles narrating the story that the dance is supposed evoke. I ask my readers to consider how silly it would be to think that the dancer has transmitted that story through her dance if the audience read the captioning. Imagine how silly it would be for an actor to stand on stage and explain the narrative instead of evoking that narrative through character and action. Well, with video games like the The Witness leading the vanguard, we are getting closer to one more consideration: imagine a developer explaining their game’s purpose and place instead of writing that purpose and place into the game world itself.

This is exactly what magicians do. We unabashedly provide the subtitles, the subtext. We tell you stories and then we show you Effects. We say “this is what that meant” and we move on to another routine. But, as Maurice Merleau-Ponty, a French philosopher most widely known for his contributions to the field of Phenomenology, states with regard to the art of painting, specifically portraits, “the meaning [of the painting] must be accomplished within the painting itself, and cannot depend upon a relationship to something extrinsic to the painting, even the person portrayed”. That is, logically, if there is to be any transmission or conveyance within an art form then it must occur through the elements that comprise that art form and nothing more/else. The art of magic is no exception.

This is the world I am trying to create. A world in which the movements of the Effect alone are all my audiences need to experience the entire gamut of human emotion. Then and only then will the people consider magic an art form worthy of the name.

Video games and magic share a cusp. And both industries are filled to the brim with staunch resistance to the changes inherent to this cusp. Both are businesses that thrive in the market law of supply and demand. Both suffer from their embarrassing standing in relation to other artistic mediums. Both are panned by the greater artistic and social communities as trivial. Indeed, it is a giant cusp, but a cusp nonetheless. But if even one of us makes it over then you can be sure that others will follow suit. It may take time. Any significant paradigmatic shift in history required ample time. I had to adjust to The Last of Us and games like Heavy Rain, Journey and Dear Esther because, while they didn’t feel like they were speaking to me in a completely different language, they certainly felt as though they were speaking to me in a different dialect.

And that’s a damn good start.

Indeed, there’s a shift happening. I can feel it deep within. While I am delighted to simply bear witness to the transformations in the video game industry, a medium I have grown up with and that has always spoken to me on one level or another, I am thankful to be an active participant in the same transformations occurring across the landscape of my first love, the art of magic.

Cheers,

- Shawn

View the original blog post on the official Shawnathanmagic Wordpress Website.http://shawnathanmagic.wordpress.com/