Scarcely a year goes by without smartphone, tablet and computer manufacturers releasing yet another new model. And this never-ending stream of improved digital products means that older devices are often disposed of, whether relegated to a junk drawer or traded-in, recycled, sold or donated to others. But when you dispose of a device, are you certain you’ve securely deleted all of your personal data?

In a study recently presented at the Proceedings of the Seventeenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security, master’s student Jason Ceci and Professor Hassan Khan at the University of Guelph’s School of Computer Science and Professors Urs Hengartner and Daniel Vogel at the Cheriton School of Computer Science found that many users leave sensitive personal data on their devices.

L to R: Master’s student Jason Ceci and Professor Hassan Khan of the University of Guelph’s School of Computer Science, Professors Urs Hengartner and Daniel Vogel of the University of Waterloo’s Cheriton School of Computer Science

“Your smartphone, tablet, computer, memory card, and external drives contain a lot of personal data,” said Professor Hengartner. “Everything you can imagine — your emails, contacts, messages, photos, documents, passwords, financial records and more.”

Given how often people upgrade their devices — typically about every three years for a smartphone and about five for a computer — it’s important that users understand how not to inadvertently leave sensitive data behind.

“There are many reports of people who have found images or info on devices they bought secondhand,” said University of Guelph’s Professor Khan, who previously was a postdoctoral researcher at the Cheriton School of Computer Science. “Although several studies have estimated the scope of the problem, our study is the first to investigate this from the perspectives of users to examine their decision-making processes.”

To understand why users often fail to digitally sanitize their devices — a process where data is removed from a device and has a low chance of being recovered — the research team surveyed 131 people who had recently listed an item for sale on online marketplaces such as Kijiji. They then conducted in-depth interviews with 35 people over Google Hangouts and Skype to better understand their decisions.

“Among the participants surveyed, 73 per cent held onto at least one device because of privacy concerns, because they use it as a back-up, or because they couldn’t be bothered to sell it,” said Professor Hengartner.

But of those who sold, donated, recycled or returned the device to the manufacturer, only 62 per cent used the secure factory reset option to erase their data. Another 25 per cent used an insecure method, such as moving files to the recycle bin or trash can then emptying it, while 8 per cent did not remove their personal data at all.

“A factory reset is really the best way to remove your data,” Professor Khan explains. “But many users chose to just delete their files, not realizing that these files could be easily recovered. When we manually delete a file, the file is still there. Only the record for how to access the file is deleted. It’s like we took off our house numbers and removed our street signs. Our house would not be gone. It would be harder to find, but it would still be there.”

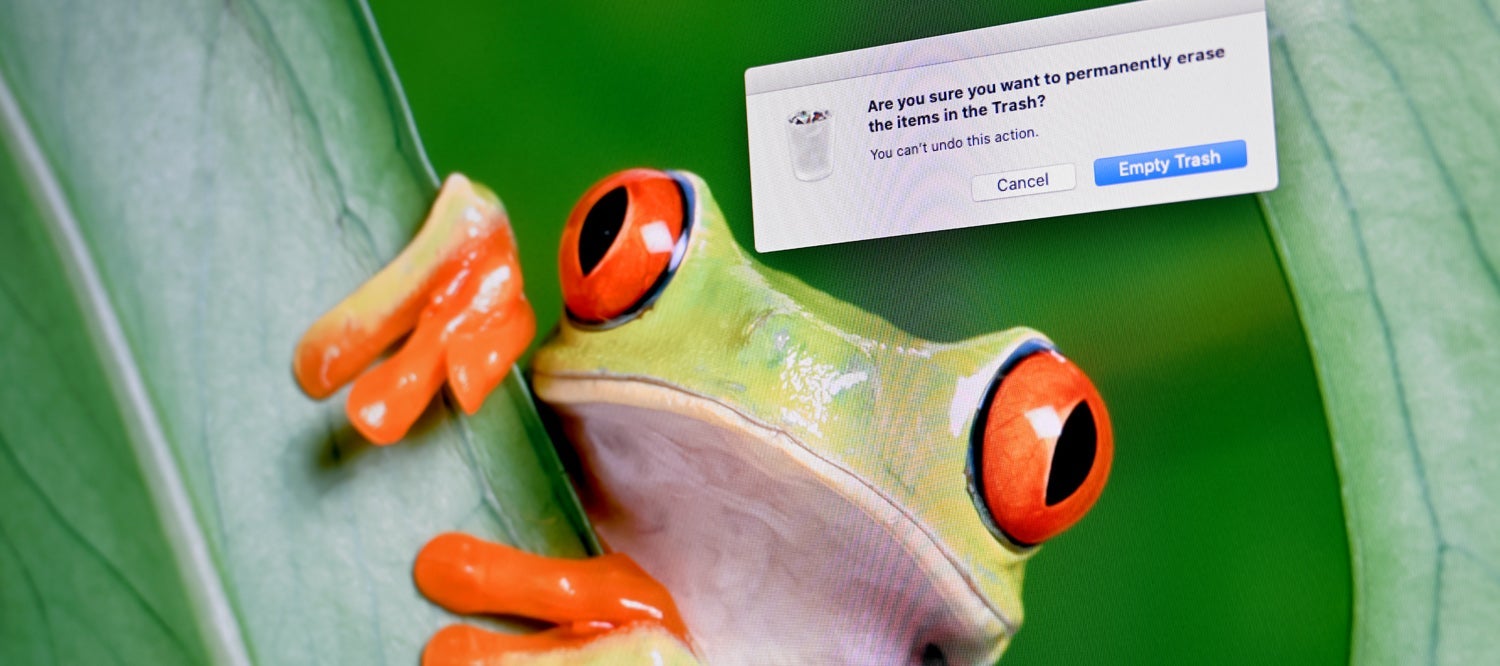

It doesn’t help that the prompts computers give users are misleading. When you manually delete a file — drag a document into the trash can on a Mac or the recycle bin on a PC and select delete — your computer asks, “Are you sure you want to permanently erase these files?” The phrasing is deceptive as it’s not a permanent deletion and the process is really akin to removing the number from a house.

“Device manufacturers and companies that develop operating systems need to fix these prompts and interfaces,” Professor Hengartner said. “The problem is seen across devices. Your digital camera has a ‘format memory card’ or ‘delete all photos’ option, but neither securely deletes photos from the card. That can be an issue because to make a camera easier to sell you might leave the memory card in it so a potential buyer can test or use the camera right away.”

Although secure sanitizing tools are available and some are built into current operating systems, it can take many minutes, hours even, to erase all information securely from a hard drive, solid state drive or memory card — what’s known as zero filling — such that its contents are completely overwritten and unrecoverable. And since secure deletion takes a long time, people might not be bothered to do it when they dispose of a device.

“Even if people go to the trouble of securely deleting their files, they may forget that personal data can be stored elsewhere,” Professor Hengartner said. “You may delete your files from your computer’s drive, but forget to delete your browsing history, the passwords saved by your browser, or log-in information stored by an app.”

This is an area where device manufacturers can play a critical role to ensure people securely delete their information from a device.

“Artificial intelligence techniques could be used to detect when users are disposing their device, such as when users are manually deleting data across the device, and then guide them to perform a secure procedure,” Professor Khan said. “And retailers who accept used devices for resale or recycling should be transparent about how they will sanitize the devices.”

It’s not just an issue of privacy.

“This is very much an environmental issue, too,” Professor Hengartner explained. “Most people know that their devices have sensitive data on them, so they may be reluctant to donate or sell them when they buy a new one. These older devices are often still functional and powerful enough for many people, but they sit in a drawer or are intentionally destroyed instead of being sold or given to someone because the original owner is concerned that the device contains sensitive personal data.”

To

learn

more

about

the

research

on

which

this

feature

is

based,

please

see

Jason

Ceci,

Hassan

Khan,

Urs

Hengartner,

Daniel

Vogel.

Concerned

but

Ineffective:

User

Perceptions,

Methods,

and

Challenges

when

Sanitizing

Old

Devices

for

Disposal.

Proceedings

of

the

Seventeenth

Symposium

on

Usable

Privacy

and

Security,

August

9–10,

2021.