They kept the details of their work quiet for years, just one of the many requirements of collaborating on a sensitive project with the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

But now that their compact, one-of-a-kind antenna has made a public splash, blasting off from India this week as a key component of a microsatellite on a mission to test new technologies, Waterloo Engineering researchers are ready to celebrate their success.

They’ve been good-naturedly pressing Safieddin (Ali) Safavi-Naeini, who led the complex effort as director of the Centre for Intelligent Antenna and Radio Systems (CIARS), to spring for a fancy dinner to mark the achievement.

“I’m still resisting,” jokes the electrical and computer engineering professor. “Maybe we can end up eating some pizza or something."

Truth be told, Safavi-Naeini is as delighted as anyone by their extremely high radiation efficiency antenna for identifying and monitoring marine traffic from space, improving safety using technology known as the Automatic Identification System (AIS).

Overcoming major challenges

One of the main challenges was making the antenna small enough, and only with materials and fabrication methods approved for use in space, to go aboard the Canadian Maritime Monitoring and Messaging Microsatellite (M3MSat), a craft about the size of a household dishwasher that is now orbiting more than 500 kilometres above Earth.

The net result after almost four years of design, redesign and rigorous testing is a complex metallic structure housed in a box measuring about 35 centimetres square and five centimetres high, and weighing less than two kilograms.

“You can imagine how happy we are that for the first time one of our antennas has gone into space,” Safavi-Naeini says. “We have been waiting for this moment for the last few years.”

The role of CIARS in the project, which also includes testing devices to ensure data continuity and measure static energy, as well as a new type of generic satellite platform, involved collaboration with the CSA and COM DEV International (now Honeywell Canada) of Cambridge, which built the small spacecraft.

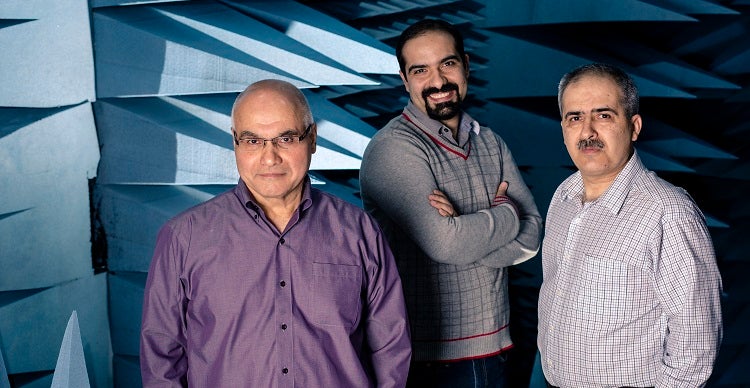

Security considerations meant only core members of the team – that included professor Safavi-Naeini, recent Waterloo Engineering doctoral graduates Aidin Taeb and Mehrbod Mohajer, and the assistant director of CIARS Reza Rafi – were privy to its full scope and purpose. Others who worked on aspects of it thought they were only doing theoretical research.

“We are honoured to have been trusted by the Canadian Space Agency and COM DEV to do this design because it was a very sensitive project from many points of views,” Safavi-Naeini says, noting there are some details he still isn’t at liberty to disclose.

Although it was difficult at times navigating the different work cultures in play, he says the process was a “textbook example” of experts from government agencies, private industry and academia working together to produce impressive results.

Safavi-Naeini considers that one of the project’s most important lessons and he looks forward to using it on future endeavours.

“By putting all of these core competencies together, we can do things that none of them can do individually,” he says.