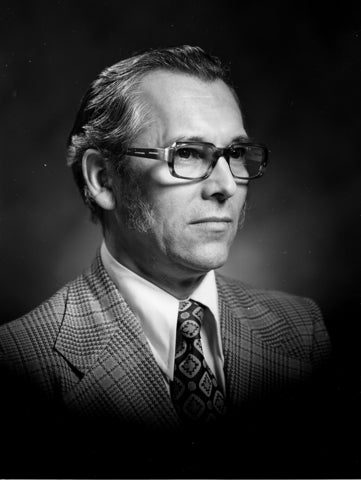

Remembering Grebel's First Chaplain

At Grebel, we remember Walter Klaassen as one of the foundational figures in our college’s history. Walter was not only the first chaplain, but also the first dean of students, a founder of the University of Waterloo’s Religious Studies department, and (with Winfield Fretz) one of the first two faculty members at Grebel. He was a scholar of the Radical Reformation, an articulate pacifist, a public intellectual, and a kind but deeply principled man.

Walter came to Grebel in 1964 from Bethel College in Kansas, attracted by the new vision for a Mennonite college embedded within—and fully engaged with—a growing public university. When he arrived at Grebel, construction on the new building was finished, but the culture and spirit of the place had not yet been built. Walter helped lay the foundations for that culture—one student, one chapel service, and one lecture at a time.

Later in life, Walter made a point of stating that, “My involvement at Grebel was a joint effort with Ruth.” In addition to managing the household while Walter was absorbed with the task of starting a new college, Ruth was an accomplished peace activist in her own right, addressing the United Nations General Assembly on the topic of disarmament in 1982.

One of Walter’s conditions for accepting the role at Grebel was that chapel attendance would be voluntary—unlike most other Mennonite colleges of the time. He reasoned that coercing religious participation was neither consistent with Anabaptist convictions, nor an effective strategy for engaging students in the unsettled 1960s— especially at a Mennonite college where most students were not Mennonite. “People should come because they want to,” he said.

Nevertheless, he paired his conviction about religious voluntarism with a clear commitment to his role as a chaplain. Walter was a deeply pastoral presence for students. He and Ruth welcomed students into their home, listened patiently, shared meals, and offered quiet guidance. I’ve heard dozens of stories from alumni who remember his kindness and support in the classroom, the chapel, and around the dinner table.

Walter Klaassen was born in Laird, Saskatchewan in 1926, married Ruth Dorean Strange in 1952, completed his PhD at Oxford University in 1960, came to work at Grebel in 1964, and died in fall 2024 at the age of 98.

He had the gift of being both exacting and encouraging. Arnold Snyder recalled handing in a paper he thought was pretty good—only to receive the lowest mark of his undergraduate career. “In retrospect, the paper wasn’t very good,” Arnold said. “But rather than discourage me, it urged me on.” (Arnold later became a distinguished scholar of Anabaptist history and a colleague of Walter’s at Grebel.)

Walter also wrote and spoke out passionately on contemporary peace issues—from just war theory to the ethics of welcoming American draft dodgers during the Vietnam War. He believed that history must speak to the present, and that the gospel had political consequences. A sign that read “Work For Peace” used to hang underneath a cross on the wall in his office—expressing his belief that faith must be lived out in everyday life.

Seminar class led by Walter Klaassen, 1969

Walter taught courses in biblical studies and Anabaptist history, but his reach extended far beyond the classroom, and far beyond Grebel. His works on the early Anabaptist leaders Pilgram Marpeck and Michael Gaismair were important contributions to the study of the Radical Reformation. He translated several sixteenth-century Anabaptist texts into English, making these voices accessible to new generations of readers. His book Anabaptism: Neither Catholic nor Protestant has remained in print for over fifty years, and continues to introduce readers to Anabaptism as a distinct Christian tradition.

Walter continued to be a productive scholar and peace activist well into his later years. His son Frank remembers that he gave his final academic lecture at age 91—arriving with a map, two index cards, and complete command of the room. He continued to translate Anabaptist and Mennonite historical texts up to his death.

Those of us who work at Grebel today inhabit a culture that Walter helped to build. Much of what we take for granted here bears his mark—the tone of our chapel services, the mix of academic and residential life, and our continued commitments to Anabaptist-Mennonite studies, theological education, and peace and conflict studies.

Last year, I was fortunate to be part of an online conversation with Walter to talk about Grebel’s history. He said that he sometimes thought of Grebel as “his kid,” and that its growth had far exceeded what he imagined in 1964. We asked him if he had any advice for us. He smiled and said, “No, I think not, because I’m not there. But I would say, carry on with the programs and the direction in which it’s going. I am always so gratified that I was able to be part of it at the beginning to get this thing going.”

We’re grateful for that too.

Dedication Beyond the Classroom

I came to live at Grebel as a second-year transfer student. I was a United Church kid, and I didn’t know anything about Grebel. I was just looking for a place to stay, and luckily a last-minute space opened up.

In order to stay in residence, I had to take a Grebel course. I chose “The Quest for Meaning in the 20th Century,” taught by Dr. Walter Klaassen. After I submitted my first paper, Dr. Klaassen asked to meet with me. He explained that although I had good ideas, my sentence structure and grammar would cost me 30–40% on every paper. If that didn’t change, I wouldn’t make it through second year—let alone to graduation.

Then he did something amazing. He offered to review every single paper I wrote (not just for his class, but for all my courses) on the condition that I gave him my drafts 72 hours before the deadline. For the entire year, I’d either slip papers under his office door or bike to his house, where Mrs. Klaassen would sometimes offer me a cup of tea. The next day, I’d pick up the marked-up version from his office or his secretary. This went on through my third and fourth year too.

Years later, when I was working in the Ontario Premier’s Office and the Attorney General’s Office, I was asked to shift from policy to communications. When I asked why, they said, “Because you’re an excellent writer.” I owe that to Dr. Klaassen, who gave so much of his time to helping me succeed at university.

—John Marshall (BES 1985)

The Quest for Meaning

As a 17 year-old, way out of her comfort zone, I took Walter’s class “The Quest for Meaning in the 20th Century” and was pushed in so many ways. I don’t remember much about the course other than being asked to think in ways I had never been asked before. I reconnected with Walter years later when he moved to Saskatoon. Eventually he began attending my congregation at Nuntana Park Mennonite Church, and we would have our weekly hug.

I saw him in the hospital several days before he died. I reminded him of that undergraduate class, “Quest for Meaning” and he asked, “Did you find it?” Walter showed me that the search for meaning is a quest that lasts a lifetime. He modeled that, and he encouraged his students and friends to do the same.

—Geraldine Balzer (MA 1983)

Geraldine Balzer (middle) with Walter Klaassen and Ruth Klaassen