Title of Contents

Articles

Editorial

Marlene Epp

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Mennonites and the Artistic Imagination

Margaret Loewen Reimer

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

The Painted Body Stares Back: Five Female Artists and the “Mennonite” Spectator

Magdalene Redekop

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

A-Dialogue* with Adorno: So, What About the Impossibility of Religious Art Today?

Cheryl Nafziger-Leis

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Performative Envisioning: An Aesthetic Critique of Contemporary Mennonite Theology

Phil Stoltzfus

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Book Reviews

Disquiet in the Land: Cultural Conflict in American Mennonite Communities

Rachel Waltner Goossen

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Homefront

Frances H. Early

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Whose Historical Jesus?

Adelia Neufeld Wiens

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Visions of Jesus: Direct Encounters from the New Testament to Today

James Gollnick

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Literary Refractions

Introduction

Hildi Froese Tiessen

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Can a Mennonite Be an Atheist?

Dallas Wiebe

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Driving with Rumi

Jeff Gundy

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

The Little Clerk

Jeff Gundy

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

’78 Chevy

Julia Kasdorf

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Reflections

From Anna Baptist and Menno Barbie to Anna Beautiful

Julie L. Musselman

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

When Two Plus Two is More Than Four: A Saga of Collaborations

Carol Ann Weaver

Full article (HTML) | Full article (PDF)

Table of Contents | Articles | Book Reviews | Literary Refractions | Reflections

Editorial

Marlene Epp

The Conrad Grebel Review 16, no. 3 (Fall 1998)

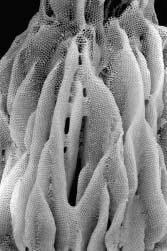

The artist within any society or community is frequently the one who shocks, provokes, inspires or, perhaps more often, is misunderstood. The work of Vancouver and Saskatoon-based artist Susan Shantz has alternately shocked and delighted the Ontario Mennonite community that she grew up in. Her Ancestral Spirits: Bed that adorns the cover of this issue playfully celebrates and satirizes such Mennonite motifs as ancestry, progeny, and sobriety. Yet the cartoon reproductive organs that practically jump off the figures startled and disturbed some viewers when the piece was exhibited. The work spoke both about and to the ethnic and religious heritage of the artist. Shantz’s more recent work, Satiate (not pictured) – an assemblage of household objects on a massive fiberglass table, all encrusted in dried tomato paste – is equally provocative but the linkages to her background are less obvious.

The articles in this issue offer varying perspectives on the overall theme of the arts and aesthetic values as they intersect with religious culture and theology. The oft-times tenuous and suspicious relationship between artist and theologian or between artists and the religious communities they identify with is not an easy subject of analysis. When the theological orientation and ethno-religious community is the Mennonites, the relationship is made more complex by a heritage of iconoclasm, an emphasis on simplicity and functionality in material life, and general suspicion of those ‘liars’ who create out of their imaginations.

The contributors to this issue – some artists themselves, others observers of the arts – all come from a Mennonite background. Each has grappled, at some level, with the place of the arts in a community which prioritizes the voice of the theologian and pastor. Margaret Loewen Reimer most directly examines the uneasy place of the ‘artistic imagination’ in the Mennonite faith community. She suggests that in its tendency to deconstruct and reconfigure meaning, art is the language needed to revitalize faith in a world of contradictions. Magdalene Redekop examines the work of five female artists, all with Mennonite roots. She goes beyond an analysis of the ways in which their varied forms of artistic expression speak from their heritage, and intriguingly asks whether Mennonites have particular ways of ‘viewing’ visual art based on that shared heritage. She places herself in the role of spectator and suggests that the inherited fear of ‘image’ and its subordination to ‘word’ has ironically drawn Mennonites in a powerful way to visual representations, hoping that they might see something of themselves in the work of art. The spectator thus becomes the specter.

- Articles by Cheryl Nafziger-Leis and Phil Stoltzfus are based on papers developed for a forum on Aesthetics and Mennonite Theology at the 1998 American Academy of Religion meetings. Nafziger-Leis, in particular, takes a highly philosophical approach to the question of ‘Is religious art (im)possible?’ Having engaged in “A-Dialogue” with Theodor Adorno for the past number of years, she describes a shift in her own position on art as ideology and concludes that art can be transcendent, spiritual, even religious, but only if it does not strive to be such. In an essay akin to philosophical art itself, taking the reader from Bertolt Brecht to MTV to Paul Tillich, Phil Stoltzfus suggests that aesthetics – “the philosophical reflection upon the meaning of artistic experience” – has been more problematic for Mennonites than artistic expression itself. As a theologian and an artist, Stoltzfus argues against the mutual exclusivity of theological and artistic language. He proposes a model of performative envisioning in which Mennonite theologizing draws not only on historicism, biblical hermeneutics, and ethics, for instance, but also on sensual sensibilities, worldly engagement, and that which is experiential and improvisatory. In a sense, we are brought back to a celebration of the artistic imagination theorized at the outset by Margaret Loewen Reimer. Tuning in to the aesthetic possibilities of the task may indeed awaken the Mennonite theological imagination.

Two artists offer Reflections in this issue. Growing up in a conservative Mennonite community, fashion designer Julie Musselman struggled with personal ideas and ideals about beauty that fit neither the plain and modest Anna Baptist of her religion, nor the superficial and overdone Menno Barbie. She observes that her church’s emphasis on not looking beautiful resulted in an obsession with personal appearance; rejecting the image became the idol. Musselman’s aesthetic journey ended up with Anna Beautiful, for whom beauty encompassed much more than the physical. The second Reflection, by musician/composer Carol Ann Weaver, chronicles a career of collaboration, where different artistic media fuse together in the creative process.

If there is a connection between the articles of this issue and the Literary Refraction by Dallas Wiebe, it may lie in the nature of the questions posed. Like many artists, who often turn the doctrinal and historical canon upside down or accepted ‘truth’ inside out, Wiebe asks whether a Mennonite can also be an atheist. The Refractions in this issue include poems by Julia Kasdorf and Jeff Gundy.

In a sense, all the writers in this issue and their subjects are ‘shattering images.’ While not following the example of some Anabaptists who literally smashed church icons, they challenge conventions that can be more akin to idolatry than any creation from the artistic imagination. I hope you are challenged by these diverse musings on the creative muse.

Marlene Epp, editor

Table of Contents | Articles | Book Reviews | Literary Refractions | Reflections

Mennonites and the Artistic Imagination

Margaret Loewen Reimer

The Conrad Grebel Review 16, no. 3 (Fall 1998)

Margaret Loewen Reimer, who has a PhD in English from the University of Toronto, is associate editor of the Canadian Mennonite. This article is condensed from a series of three lectures given at Canadian Mennonite Bible College in January 1998

In 1984, a film crew came to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, to make the movie, Witness. This Hollywood invasion, both literal and artistic, caused an uproar among Mennonites. The Gospel Herald printed vehement attacks on Hollywood’s exploitation of the Amish, written by “experts” who themselves had “publicized” Old Order folk through their books, films, and photographs. One of these experts defended himself by contrasting documentary films that serve “historic and instructional purposes” with Hollywood movies that “alter reality in any way that will entertain with maximum profit.” Jan Rubes, a Canadian who played the Amish father in Witness, said that the protests didn’t come from the Amish, but from “professors . . . who write books about the Amish and exploit them more than anybody” (CBC’s Morningside [radio program], Feb. 15, 1985).

I’ve often thought about this debate in relation to Mennonites and the arts. Are some subjects off-limits to artists? Who gets to tell the story? Which story? In exploring these questions, I propose to look at what it means to imagine, what language we use to convey the truths of the imagination, and what imaginative creativity has to do with faith. I come to this topic out of my experience as a student of literature and as a Mennonite journalist with a special passion for the arts.

During a discussion on CBC’s Morningside (July 2, 1996), someone asked, “Why do so many good singers come from the Mennonite tradition?” Saskatchewan musician Connie Kaldor was quick to reply: “Because they can’t dance.” Seriously, why is the art of singing so acceptable, while the other arts, particularly theater and dance, have been suspect? It’s not just that we have always been a singing people (in fact, we haven’t – Conrad Grebel, our eminent spiritual ancestor, was opposed to any music in worship). The reasons have to do with the very essence of our faith.

In Julia Kasdorf’s poem, “The only photograph of my father as a boy,” the young Amish boy is transformed by the click of the camera: “That click, something flew out of him . . . And something flew in.”[1] The camera – that instrument of illusion, of forbidden images, of pride – snatches away an essential part of the boy’s heritage and replaces it with the arrogance of worldly knowledge. This image captures the Mennonite suspicion of art.

When Ontario bishop Jacob H. Janzen came to Canada in 1924, he was already known for his German dramas and fiction. In 1946 he wrote: “When I came to Canada and in my broken English tried to make plain to a [Swiss] Mennonite bishop that I was a ‘novelist’ . . . he was much surprised. He then tried to make plain to me that ‘novelists’ were fiction writers and that fiction was a lie. I surely would not want to represent myself to him as a professional liar. I admitted to myself, but not aloud to him, that I was just that kind of ‘liar’ which had caused him such a shock.”[2]

Writers such as Janzen and Arnold Dyck reflected what we might call a “Low German imagination,” the earthy humor of rural life. But something else “flew in” that moment in 1962 when Rudy Wiebe’s novel, Peace Shall Destroy Many, destroyed the peace of Canadian Mennonites.[3] Why was Wiebe’s novel so threatening? For one thing, he was an insider – editor of a denominational magazine, Mennonite Brethren Herald. He was looking at Mennonites in a new way, scrutinizing the sacred and the profane through the same artistic filter. And he was translating Mennonite experience into a new language: the language of English, the language of fiction. This novel signalled a new imagination breaking into Canadian Mennonite life.

The biblical imagination

Art is dangerous, and Mennonites have always recognized that. It’s not only that it is unpredictable or uncontrollable. At a fundamental level, the act of creating can be an act of hubris, of competition with the One Creator God who can’t be defined or named, and who demands that we make for ourselves no “graven image or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” (Exodus 20). This biblical warning against images has been used by various branches of the church to warn against any visible depictions of God and even against art itself. “Woe to him who strives with his maker,” says Isaiah 45.

The commandment against images isn’t just some quaint warning against foreign idols. At stake is the belief that God can’t be understood or portrayed by even the farthest reaches of our imagination. At stake is the belief that divinity is something else than the world we know through our senses, the world out of which we create. Jahweh communicates with his people not through a tangible presence or visual image but through the Word. And so the Hebrews become supreme artists of the word – from poetic declarations of faith to blood-curdling tales of sex and violence.

To pit word against image, however, is to misrepresent biblical artistry. For the biblical word carries within itself a host of imaginative forms and elements that have inspired the artistic imagination through the centuries. The warning against images did not deter the ancient Hebrews from longing for the sight of God, for visible expressions of the invisible. “Show me your face,” begged Moses (Exodus 33). But he only got to see the effect of God passing by – the back of God, says the story. “I saw visions of God,” proclaimed Ezekiel as he described fantastic winged creatures and four vast wheels and the great throne with the creature of light and fire.

In fact, one could say that the fundamental aspect of the biblical imagination is not iconoclasm but an obsession with “image.” For the Hebrews, of all people, were intensely engaged in making the invisible visible, with translating spiritual reality into human activity. We human beings, after all, are images of the divine. This image-consciousness expresses itself in an obsession with the body. The Bible is full of body language: the church as the body of Christ, the resurrection of the body, Israel as the bride of God (evoking the Genesis image of marriage as “one flesh”). What counted most for the Hebrews was bodily obedience. The biblical writers never shy away from exploring the implications of the body – in all its degradation and its glory – culminating in the very embodiment of God in human form. This vision of incarnation, the Word made flesh, is a central aspect of the biblical imagination. It holds in tension the mystery of divinity with the solid immediacy of human flesh, the same impulse that drives all art.

One could say that the Bible has left us a legacy of ambivalence about art. While the people are to avoid physical representations of divinity, their temple is to convey all the splendor and color they can possibly muster (Exodus 26). And the biblical writers have no qualms about constructing glorious verbal images. In Revelation, the angel says to John, “Don’t write this down. All the mysteries will be revealed at the end of time.” Meanwhile, of course, John writes furiously, giving us some of the most fabulous images in all of literature.

The artistry of the Bible, then, springs from the defining motives of any art – to make the invisible visible, the untouchable touchable. And in many ways we have the same suspicion of the biblical imagination as we have of other art. To Mennonite Christians, the Bible is about faithful discipleship and love and piety. What are we to do with all those mythic tales of floods and monsters, dreams and magic, and the end of the world? And what about those horrible stories of murder, rape, and incest?

Like any good art, it doesn’t all fit easily together – even the images of God seem contradictory: we see a God who hurls threats at his wayward people and wreaks vengeance on the enemy, alongside a God who embodies grace and love of enemies. We are confronted with a grand vision of the universe, as well as a messy world ruled by pettiness and scheming. The Bible is full of clashing images and contradictory messages which can only be held together by the imagination.

The word “imagination” comes, of course, from the word “image” – a representation or embodiment of an idea or person. It helps to distinguish between the imaginative and the imaginary, the latter being closer to our understanding of illusion or fantasy. The imagination is the power to form mental images, to perceive something not present to the senses. Samuel Taylor Coleridge described the imagination as a power that seeks the truths which underlie our fantasies and dreams, a power that unifies experience and fantasy in a new understanding.[4] For Northrop Frye, that great organizer of the mythic realm, the imagination is what makes sense of the world. The great biblical myth – the story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation – becomes a “myth to live by” in a way that purely literary myths cannot, says Frye. It takes on ultimate significance, ultimate reality, for those who believe.[5]

The Hebraic influence

It was my fascination with the interplay between the biblical and the literary that drew me to a doctoral thesis on “Hebraism” in English literature.[6] The starting point for my thesis was Matthew Arnold’s claim that two forces – Hellenism and Hebraism – are the major shapers of western culture. Arnold defined Hellenism (or the Classical tradition) as the love of “pure knowledge,” that which invests life with clearness and radiance, governed by flexibility and “spontaneity of consciousness.” In contrast, Hebraism – a word he coined – is “the energy driving practice,” the overriding obligation to “duty, self-control, and work,” rooted in earnestness and “strictness of conscience.”[7] In other words, Hebraism holds goodness to be the highest value; Hellenism, beauty.

In literary terms, “Hebraism” has become identified with the preference for the natural (real) over the artificial (ideal), and the individual struggle over the realized universal. By this definition, the artistry of our day is dominated by Hebraism, fed by the spirit of post-Enlightenment materialism that locates the “real” in the empirical world, not in the supernatural or ideal sphere. That poses an interesting dilemma for Mennonites. Our affinity for biblical Hebraism – the focus on morality and hard work, our suspicion of “fancy” – has led us straight into the promised land of modernity. We tend to be uneasy with art that is simply fanciful, playful, or beautiful for its own sake.

Not that Mennonites have been exempt from the urge to beautify and create. We have a history of beautiful gardens, embroidery, handicrafts, and quilts. But art has been considered a servant – a servant of function and of faith. That’s why singing is so acceptable – it is the ultimate communal activity, a harmony of the aesthetic and religious. Individual artists risk the sin of pride and undermine community. But wherein lies the real pride? Is it in daring to create, in putting ourselves on display? Or does the greater pride consist in refusing to create, to perform, to develop our God-given ability to imagine? Mennonite sectarianism has been built on the drive to stay simple and separate, to protect what we have, to remain “self-righteous.” To write, to paint, to compose, is to become publicly vulnerable, to risk interpretation and misunderstanding. It means not being able to control the reviews.

For some artists among us, the risk of going public has been high. At the same time it has meant a kind of resurrection – both for the artist and for Mennonite self-understanding. The artistic imagination is providing new perspectives on old stories, new angles from which to examine ourselves. Sometimes perceptions clash and people of religious faith feel violated by art. For artists, too, can be tempted to close their imaginations to the complexity and variety of religious faith. That’s why the church and theorist need to talk to each other.

Shattered images

At the Mennonite Reporter, now Canadian Mennonite, we have tried to keep in touch with what Mennonites are doing in the arts. That’s because we believe that the artistic imagination and the religious imagination are so closely related to each other. But we keep getting the same questions: How can you call poet Patrick Friesen a Mennonite when he spurns the church, or singer Ben Heppner a Mennonite when he grew up in the Alliance church? Several assumptions have guided our thinking:

- In literature, at least, there is an identifiable body of art that is shaped by a Mennonite ethos – by the beliefs and customs of a distinctive community.

- “Mennonite artist” is a useful code word for those whose art reflects their experience of the Mennonite community.

- Artists’ responses to their Mennonite heritage vary greatly – from condemnation to comedy, from nostalgia to deep religious commitment.

But is there really such a thing as a Mennonite ethos or a Mennonite story? Historians in the past few decades have moved decisively into a polygenesis theory of Mennonite origins. Mennonite artists are deconstructing our assumptions in even more discomforting ways.

“Be careful, memory will trick you,” says writer John Weier. “It tells you everything you wish to know. Nothing you remember is true. Father remembers only the good things. That’s his story, the good and happy story. The rest he can blame on the Russians. Mother remembers nothing. Was it really that bad?”[8]

Which stories are true? Memory will trick you. Your parents will trick you. Your church will trick you. Look deeper to find meaning, if there is any. That’s the creed not only of artists but of many seekers in our time. There are as many stories as there are individuals and everyone has the right to tell them. In this postmodern time, the code we had to decipher meaning is disintegrating and we are left with discontinuous pieces and silences. Our attempts to create, some say, are only games we play against the darkness. How do we believe in such an environment, we who assume meaning not only in words but in The Word? If the code to our faith is lost, we are left with nothing more than superstition.

Ironically, even as art deconstructs or reconfigures meaning, it offers perhaps the greatest potential for renewed faith. I believe profoundly that the artistic imagination can help us hold together the many clashing realities we live with, to bridge the vast gulf between biblical understandings and the creeds of our own time, between the competing gods of our culture and our personal truths. We need more than one language, one understanding, to make any sense of life. We know the imagination can be dangerous, but it can also help us face the contradictions and hold them together within a larger understanding.

Patrick Friesen speaks of living “with one foot in the shade / trying to be true and double-crossing you every step of the way . . . .”[9] The poet stands on the divide between sun and shade, truth and deception, a lost soul who yet dares speak a word. He also stands on the divide of history as he looks back at his Mennonite boyhood:

I know the Steinbach boy is dead

betrayed and murdered seventy times seven by me and anyone else who helped

and still I go to the cemetery again and again

because it’s a beloved place

where horses used to wheel and boys played with fire.[10]

The Steinbach boy may be dead, killed by a too-narrow vision and by other factors, but the poet still goes back to the “beloved place” which shapes his imagination.

That doesn’t sound postmodern to me. It’s a leap of faith, a balancing act – between past and present, coherence and chaos, the Mennonite child and the modern man. In fact, many Mennonite artists find themselves in exactly this discomforting space. “Insofar as the writers . . . continue to feel the pain and confusion that attends the demise of a coherent order, they are modernists. Where the pain shows signs of disappearing altogether, their work may begin to reflect something of the numbing solipsism of the postmodern temperament,” said Hildi Froese Tiessen in a journal featuring Mennonite writing.[11] It is into this space that our imagination projects us.

Poet Sarah Klassen reminds us:

Abandon foolish dreams of arrival.

Resign yourself to the absolute

necessity of departure. Dead weight

of cumbersome luggage must be cast off.

When you become translucent, luminous

as morning

you can travel where you will.[12]

Abandon foolish dreams of arrival. Learn to live with the uncertainty, the incompleteness. Strive to become translucent, says the poet, permitting the light to pass through. Good art, like good theology, has that transparency – it allows truth to shine through it to illuminate the human condition. It may not give us answers, but it provides, as Robert Frost said, “a momentary stay against confusion.” And no matter how much today’s writers mutter about the loss of the external referent or the impossibility of meaning, I believe that every creative act is an assumption of coherence, of meaning, because all art imposes some kind of form and order on its reality.

Making connections

During my thesis defence at the University of Toronto, my examiners became most agitated over my assumption of coherence. How could I assume a connection between biblical notions and the views of nineteenth-century writers? How could I imagine that one could trace a strand of thought through different centuries? In a literary climate enamoured with disjunction and discontinuity, it was difficult to communicate.

But that is the problem we all face today. How can we presume connections between the world of the Bible and the world of television? How can our children, reared on The Simpsons and X-Files, make sense of the Sermon on the Mount? And yet, Christians believe that there is a continuity through the ages, that our story is somehow linked to the biblical story and to the history of the world. If we believe that, then we must also believe that religious truths are related to other truths, that the Bible is part of a much larger canon that includes the many cultural “texts” that shape us every day. That means daring to dress ancient truths in contemporary garb. One of the great pleasures of my studies was discovering the medieval mystery plays. These biblical drama cycles, performed on the Feast of Corpus Christi, translated the whole story of the Bible – from creation to doomsday – into a spectacle of entertainment. Biblical heroes were humanized in shocking ways and the “bad guys,” especially the devil, made obscenely wicked. Five centuries later, these plays still brim with humor and ingenuity. Perhaps inspired by this medieval audacity, I wrote a Christmas pageant some years ago which included Old Testament scenes not usually associated with Advent. One scene was a spiteful squabble between Hosea and Gomer which, in the hands of ten-year-old actors, turned into hilarious farce.

The congregation was perplexed, but for me the experience was an exhilarating experiment in exploring the biblical imagination. With my own children, I have tried to inspire an inclusive imagination, to place the treasures of the faith beside the treasures of our cultural heritage: Are Samson and Hercules really so different? How does Star Wars compare to Israelite wars? Does Tamar’s abuse speak to abuse in our day? If we try to “protect” the Bible by shutting it away in a religious closet, confining it to a safe, intra-textual discussion, we withdraw it further and further from the other conversations that shape us. For we live our lives in an inter-textual debate with the world around us, a debate in which the Bible is becoming more and more irrelevant.

The language of faith

How do we speak of faith in our day? The enlightenment of our reason, which convinced us that the earth is not flat, had the unfortunate effect of flattening out our imagination. Modernism tried to convince us that the demonstrated reality of science is more true than the demonstrated reality of faith, and that empirical truth is more real than metaphorical truth. Biblical criticism, too, has often succeeded only in literalizing what was literary. While most Christians are no longer arguing about the scientific accuracy of Genesis 1, we’re still in the middle of debating the gender of God and the genetics of the virgin birth. And for most of us, “dogma” and “creed” still conjure up visions of stone tablets instead of the fragrance of poetry. These days we are seeing yet another kind of religious reductionism. Postmodern passions are seeking to escape the limits of scientism by floating away on the clouds of self-help spirituality and Celestine prophecies. They are no closer than literalists to the spirit of the biblical word.

“May God us keep / From Single vision & Newton’s sleep!” cried William Blake, whose mystical visions were a fierce protest against the one-dimensional thinking of Newtonian science.[13] In his 1963 CBC Massey Lectures, “The Educated Imagination,” Northrop Frye outlined the variety of disciplines we study and the various “languages” we need to understand them. Different kinds of experience need different ways of thinking and speaking.[14] Medieval interpreters understood the dangers better than we do when they insisted that there are at least four levels of meaning in the Bible, four ways of reading:

- The literal, not literalistic, level is straightforward reading;

- The allegorical is the symbolic meaning;

- The moral level teaches us how to live;

- The anagogical or mystical meaning speaks of future hope. All of these are important, for they apply to different aspects of reality and experience.

We need different languages for different realities in our lives. But what if these languages don’t harmonize? Think of the Tower of Babel, with its confusion of voices. We usually see the Pentecost story as the restoration of communication, of unity. But look again. At Pentecost we still have all the different voices. They may hear truth differently but they manage to communicate. How do we keep the discordant voices speaking to each other in our lives?

We can look to art for analogies. Art is created out of tension, even violence. “Art begins in a wound, an imperfection – a wound inherent in the nature of life itself,” said critic John Gardner.[15] The metaphysical poets of the seventeenth century made their mark by forcibly yoking together discordant images and ideas, thereby forging new and unexpected meaning. Art springs from the coming together of the senses, the intellect and the emotions – art, said T.S. Eliot, is “the sensuous apprehension of ideas.”[16] It can help us bring together the different realms of our experience.

One of the highlights of my recent sabbatical year in Europe was seeing the Issenheim altar by Matthias Grünewald. The large center panel of the Advent scene shows the conventional mother and child. Above Mary is a luminous vision of the God of hosts – a figure of almost pure light surrounded by impressions of a vast army. On the left panel, a lively angel orchestra, led by an enthusiastic cellist, is serenading the mother and child. But look closely, in the back of this bright orchestra lurks a demon.

That demonic figure amidst the angels speaks powerfully to me. It says that the images that jolt my comfortable faith, that clash with my preconceptions, may in fact have the most to teach me. Art that brings together the contradictions can push out the boundaries of my faith and help me contemplate a larger picture, a picture that includes the gaps and the silences. For Mennonites, the gaps may include many things. Above the pacifist Jesus is the God of armies. Behind the humble servant lurks the demon of self-righteousness. Mixed with the glorious choral harmonies are the discords and unresolved cadences. An imaginative faith recognizes that all of these are part of the picture.

But what if the larger picture includes too much for us to bear? Our culture tends toward excess, pushing the boundaries further and further to stimulate our jaded sensibilities. In our uncensored environment, can one talk about a moral imagination? Someone once asked Rudy Wiebe about the purpose of art: “The whole purpose of art, of poetry, of story-telling, is to make us better. Okay? Let’s leave it at that,” said Wiebe.[17] How does art make us better?

Morality and the imagination were linked in an interesting article on Dorothy Parker, the cynical New York writer who died in 1967. The tragedy of Parker’s career is that Parker had no imagination, said the writer. “People are always telling us how there is no connection between moral strength and artistic strength: how Picasso preyed on women, how Wagner hated Jews, how you can be a terrible person and still be a great artist. But the case of Parker reminds us that, while the relation between morality and imagination may be a complicated one, it does exist. Hope, forgiveness – these are not just moral actions. They are enlargements of the mind. Without them, you remain in the tunnel of the self. Parker was morally a child all her life. She had a clear vision of the bad, but it never taught her anything about the good.”[18]

Enlargements of the mind. Clear vision. These are criteria of judgment we should be applying to the images of our time. Popular culture these days is caught somewhere between robot wars and banal exercises in self-gratification. Excess and inanity are the ruling forces behind much of what influences us. (Maybe we should be petitioning TV networks for real sex and real violence.) To counter these visions, we clutch at political correctness and ideology. Or we take refuge in nostalgia or sentimentality. Sentimentality (“emotional promiscuity,” Norman Mailer calls it) is one of the biggest dangers to the imagination.

When I ponder the arts from a Christian perspective I always come back to that fierce southern American Catholic, Flannery O’Connor. She summarized her own artistic creed with characteristic bluntness: “My subject in fiction is the action of grace in territory held largely by the devil.” Christians are in the best position to delve into the world’s evil, she says, because “writers who see by the light of their Christian faith will have, in these times, the sharpest eyes for the grotesque, for the perverse, and for the unacceptable . . . . Redemption is meaningless unless there is cause for it in the actual life we live.”[19]

Inferior art (or would-be art) is the real violation of the commandment against images, for it circumscribes and limits the possibilities of the human spirit. It confuses “real life” with what comes naturally, not recognizing that the most natural is not necessarily the most human. True art, sometimes through abhorrent means, strives to expand our experience of reality, to reveal more angles of the truth. But that may mean less certainty. In these fragmented times, Christians are not immune to the erosion of what they thought they knew for sure. We share the world’s bewilderment with too much information and too little knowledge, the pain of too many feelings and not enough understanding. We have entered the writhing pains of a creation yearning to be reborn, as Romans puts it. Can we still speak truth? Perhaps it will be a more tentative truth, a more vulnerable truth.

“We live in an era of violent excess,” noted Robert Detweiler of Emory University in a 1997 lecture.[20] But that’s nothing new – we hear this excess already in the Old Testament: “Saul has slain his thousands, and David his ten thousands.” But the Bible also gives us examples of good excess, said this speaker, a scholar of literature and religion. Mary Magdalene invades Jesus’ privacy in a fit of bad manners and pours expensive perfume on his feet. She displays what we might call an “excess of imagination.” This good excess is evident in our time in the “stubborn will to believe.” In the midst of the postmodern shattering of the reality we knew, we reach out to infinity for rescue. This requires an act of the imagination; it is an act that “divinizes our anxious time.”

One of the most memorable images Detweiler used was the medieval image of Christ as the harrower of hell, prying open with his cross the jaws of Satan, forcing the beast to vomit up the bodies of the damned. This excessive image portrays the energy of resurrection, he said, as excess is transformed by the cross.

Sacramental reality

Several years ago, I reviewed a book called Art of the Spirit: Contemporary Canadian Fabric Art.[21] It’s a collection of liturgical art, art for worship – clerical vestments, altar cloths, banners, even coffin palls. The book bowled me over! For a Mennonite reader like me, the book should have contained a warning: “Beware the shock of encountering the spirit made visible.” The bold designs and vibrant colours, the imaginative leaps, had the effect of too-rich food after a life of bread and butter.

Included in the book was a work by Mennonite artist Susan Shantz, entitled “Cathedral II.” This multi-media piece was the only work not meant for public worship. It shows a conservative Mennonite couple sitting in an enclosed space that resembles the gothic structures of grander spaces. The description says that Shantz’s “person-sized” construction is a play on the tension between her “imageless heritage and her own need for a more visual and sensual religious expression.”

Why do we have such “artless” worship? Is it because our Protestant spirit is so intact, or do we simply lack a spiritual imagination?

I have a son for whom the visible world is a metaphor for the reality of his imagination. When he was very young, he was enchanted by the beautiful roses that were growing in our yard. “They look just like real ones,” he said to me. “But they are real,” I responded. “No, I mean like the ones in pictures.” When he was baptized, he said that the significance of that momentous act only sank in when he first ate the bread of communion. When he heard “This is the bread of the world,” my son felt for the first time that God is actually part of the physical world, the world of the senses, and not only a spiritual force.

While we believe that God is present in the natural world, Mennonites are careful not to equate God with nature or with human beings. We don’t recognize a physical presence in the bread and wine. Our Confession of Faith speaks of the Lord’s Supper as a “sign” of God’s presence. For us, God’s presence in communion is confined to the memory of Jesus or to the visible community. Is that enough?

I remember an argument between a Catholic and Protestant over transubstantiation – the belief that the bread and wine become the actual body and blood of Christ. The Protestant argued that transubstantiation is a misunderstanding of metaphor. “Religious language is always metaphor,” said the Protestant. “Yours is the misunderstanding,” said the Catholic. “For I know that I am not eating human flesh and drinking human blood. But I know at the same time that the bread and the wine have truly become the blood and body of Christ as I partake of them.” This belief moves us beyond metaphor to mystery, from memory to sacrament.

There are powerful realities in our faith that we cannot just leave as metaphor. We may try to literalize them on the one hand, or spiritualize them on the other, but they defy both categories. They are mysteries, miracles, and we believe them by faith. Take resurrection, for example. It takes us through all that we know to the “other side of reason,” as someone put it. It frees us from necessity, from the tyranny of cause and effect, by opening our eyes to a different universe. In theological terms, we speak of ontological reality, the foundation of life behind the empirical manifestations of it. In imaginative terms, we can say that faith opens our eyes to an enchanted world, a world full of sacred magic.

That sounds almost pagan, doesn’t it? One of the things that early Anabaptists rejected was the notion that certain images or certain spaces were more magical, more sacred, than others. In denouncing beautiful churches and priestly ceremony, Anabaptists believed that they were making all of life sacred. But what happened? The magic and the mystery almost vanished altogether and we found ourselves allied with the modern spirit that secularized (de-sacralized) the world. One of the ironies about atheistic communism was that its people remained much less materialistic than we in the Christian West. Someone who lived in Poland in the 1970s told us: “The Poles can hardly get bread or milk or butter in the shops, but they can buy flowers on every street corner.” They knew what nourishes the soul.

A sacramentalist believes simply that the greater may be perceived in the lesser (the world in a grain of sand, as Blake said). To see sacred magic in the physical world is to have a sacramental view of the world. A Catholic colleague of mine, Andrew Britz, brings together his sacramental tradition with a keen social conscience. “We don’t receive sacraments; we become them,” he says.[22] We are Christ’s body in the world. A Mennonite friend talks about the family as sacrament – there are moments in the experience of family when the divine breaks into our lives and God takes on flesh. We embody the sacred. We are the means of God’s grace to the world. That’s a wonderful union of sacramental and Mennonite thinking.

Today, we see evidence of a renewed imagination among us. The environmental movement is trying to recover the sacredness of nature; spiritualist movements are discovering God in every living thing; current theology, particularly feminist theology, is giving heightened significance to the body. But what kind of sacramentalism is this? It plays too easily into our culture’s sanctification of the personal without enlarging our capacity to appreciate the Otherness of reality – that which lies outside ourselves. We have much art of the body these days, but does it convey the spirit which gives it life? As Teilhard de Chardin said, “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience.” That’s a different way of seeing.

Changing images

One of the things Mennonites have experienced in the past two decades is the power of images and symbols. Look what happens when we challenge the image of God as father. Or the mode of baptism. The intensity of our response does not come from rational argument or an act of the will. Our associations with certain symbols of the faith arise from deep within us; they have shaped how we experience faith.

During a recent retreat, abuse survivors were invited symbolically to lay down their burdens by placing stones around the foot of a small cross. For some, the cross was a symbol of comfort because it represented Christ’s own experience of abuse. For others, it triggered the most painful associations of abuse and it had to be removed. They had opposite responses to this image of the Christian faith. God as father is another image that elicits extreme response. One of the current solutions is to add the image of mother or parent. That doesn’t get at the real problem, in my opinion. We’ve simply ended up in a fight over gender, which is not where we want to be. How can we contemplate the person of God in the twenty-first century? We need some radical re-imagining on that one.

As non-sacramentalists, we tend to domesticate powerful images of the faith. Think of baptism. For some, baptism demands a literal immersion; for others it is enough to symbolize an inner cleansing with a few drops of water. But look at the biblical images of salvation – death of the old person, being reborn, cataclysmic change. The picture conveyed in the Bible is not the water that washes but the flood that drowns. Can our muted practice of sprinkling convey the power of that symbol? Another symbol that has become entirely domesticated is the cross. If we really want to convey its meaning, why don’t we erect a gallows, or even better, mount an electric chair in the front of the church? Sometimes it just seems easier to choose whatever meaning fits our experience or is the most politically correct at the moment.

These days, God as parent is definitely more palatable than God as judge. And it’s easier to speak about the Jesus of good works than about the Christ who was before the creation of the world. So we choose one, instead of hanging on to the mystery. It’s hard to keep the clashing images together – you can’t get a more contradictory image than Jesus Christ who is fully man and fully God – but that is the paradoxical imagination we have inherited. We want so badly to reconcile everything and hold truth in understandable pieces, but faith isn’t like that and neither is the world. We know that truth cannot be contained or enclosed; it cannot be fixed in one place and time, in one medium. It is more like a magnet, drawing us to its centre. Our creations, our images, are attempts to reveal and to give form, but we know that just as no image can enclose divinity, so our creations and imaginings remain incomplete visions of the truth we seek.

What does all this mean for worship? Last Easter I attended a vigil which began at 11:00 P.M. on Holy Saturday. It included a candle-lit procession through the dark, ceremonies of penance and other exotic rites, and the dramatic uncovering of banners and decorating of the altar with greenery right after midnight. But the drama couldn’t really take off in that drab little room, and the glorious readings got bogged down by the stumbling lay voices. It was all a bit awkward. But maybe that’s also part of the contradiction – we mortals trying to convey the immortal.

What is the appropriate language for worship? There is a difference between public and private language, between the vernacular and the colloquial. I suggest that the colloquial is too “flat” or limiting for public worship. That doesn’t mean we have to return to the King James Bible, although on occasion we may want to. Much as I love Elizabethan language, I am convinced the church must speak in the language of today. But that doesn’t mean casual liturgy. I have a special problem with unskilled Bible reading. In some traditions, the whole congregation rises in respect when the Gospels are read. As a so-called biblical people, the least we can do is make the Bible reading a heightened moment, the dramatic focal point of worship. Public worship demands the distance we speak about in art – a stepping back from the strictly personal into stylized form and public voice.

Annie Dillard, an American writer with a mystical eye, is amazed at how casually and unconsciously we gather on Sunday mornings to worship the creator of the universe. “We should all be wearing crash helmets,” she says. “Ushers should issue life preservers and signal flares; they should lash us to our pews. For the sleeping god may wake some day and take offence, or the waking god may draw us out to where we can never return.”[23] Do our liturgies reflect our belief in an almighty God? Rites and rituals are not affectation; they are attempts to lift us above the limits of mortality and give us a glimpse of the mysterious eternal. Worship must nourish not only our personal emotions but our communal soul, not only our minds but our collective imagination. Let us end with a hymn.

Let us sing now a hymn to the healer

physician of the broken tongue,

judge of the merciful sentence . . .

Let us sing also between the lines,

the harmony of spaces,

the resonance of what is left unsaid;

sing the witless howl, on leash,

unleashed.

Let us sing to the Healer

who gathers our voice in the night

and returns it again on the Wind . . . .

In the night of our singing

the light we are given, have given,

is gathered, is given once more

in the round perfect moon of our singing.

In the pale of our night

by the wit of our tone

by the translucent bone in the teeth of our tongue

we are singing our souls into Light.[24]

Notes

[1] Julia Kasdorf, Sleeping Preacher (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992).

[2] J. H. Janzen, Mennonite Life, 1946.

[3] Rudy Wiebe, Peace Shall Destroy Many (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1962).

[4] Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “Biographia Literaria” (1817), in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Vol. 2 (New York: W. W. Norton & Co.,1962).

[5] Northrop Frye, The Great Code (Toronto: Academic Press Canada, 1982).

[6] Margaret Loewen Reimer, “Hebraism in English Literature: A Study of Matthew Arnold and George Eliot.” Dissertation for Faculty of English, University of Toronto, 1993.

[7] Matthew Arnold, “Culture and Anarchy” (1869) in Poetry and Criticism of Matthew Arnold (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1961).

[8] John Weier, Steppe: A Novel (Saskatoon: Thistledown Press, 1995).

[9] Patrick Friesen, “pa poem: singing elijah,” in Unearthly Horses (Winnipeg: Turnstone Press, 1984).

[10] Patrick Friesen, “location,” in Unearthly Horses (Winnipeg: Turnstone Press, 1984).

[11] Hildi Froese Tiessen, Prairie Fire, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Summer 1990).

[12] Sarah Klassen, “Reasons for delay,” in Borderwatch (Windsor: Netherlandic Press, 1993).

[13] William Blake, “Letter to Thomas Butts” (1802), in Blake: Complete Writings (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1969).

[14] Northrop Frye, The Educated Imagination (Toronto: CBC Enterprises, 1963).

[15] John Gardner, On Moral Fiction (Toronto: Harper Collins, 1979).

[16] T.S. Eliot, The Sacred Wood (Georgetown: Rutledge, Chapman & Hall, 1961).

[17] Rudy Wiebe in Books in Canada (Feb. 1980).

[18] Joan Acocella, The New Yorker (Aug. 16, 1993).

[19] Flannery O’Connor, Mystery and Manners (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969).

[20] Robert Detweiler, “Literary Echoes of Postmodernism” (American of American Academy of Religion, 1997).

[21] Helen Bradfield, et al., eds., Art of the Spirit: Contemporary Canadian Fabric Art (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1992).

[22] Andrew Britz, Prairie Messenger (Feb. 19, 1997).

[23] Annie Dillard, Teaching a Stone to Talk (Toronto: Harper Collins, 1988).

[24] David Waltner Toews, “The Editor’s Song,” The Impossible Uprooting (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995).

Table of Contents | Articles | Book Reviews | Literary Refractions | Reflections

The Painted Body Stares Back: Five Female Artists and the “Mennonite” Spectator

Magdalene Redekop

The Conrad Grebel Review 16, no. 3 (Fall 1998)

Magdalene Redekop is a professor in the Department of English at the University of Toronto. She is also the author of Mothers and Other Clowns: The Stories of Alice Munro.

In the beginning was the quilt. Priscilla Reimer, the curator of a 1990 Winnipeg exhibition entitled “Mennonite Artist: Insider as Outsider,” noted that “there is no identifiable tradition of Mennonite art” unless you include “fraktur, quilting, and other forms of decorative design.”[1] In Primitivism, Franz Boas cites an analogous example. Among the Californian Indians, basketry is the chief industry. “Basket-making is an occupation of women and thus it happens that among the Californian Indians only women are creative artists.”[2] Quiltmaking is an occupation of women and thus it happens that among Mennonites only women are creative artists. This cheerful logic is belied by the fact that many of the artists in the 1990 exhibition (male and female) told Priscilla Reimer that they were artists in spite of, not because of, being Mennonite. We are taught to begin, of course, with the Word, and the scripture that looms large is the writing on the tablet that Moses brought down from the mountain: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.” The heritage of contemporary Jewish women artists is similar in many ways, with the important difference that within Judaism decorative art has a central place in religious rituals. Reimer notes that the work of Mennonite artists can be seen as an attempt “to fill the emptiness left by a heritage devoid of visual imagery.”[3]

I want to ask questions in two inter-related areas. The first concerns the art itself. When these Mennonite artists do fill the void, are the works they produce in any way influenced by that nonrepresentational decorative tradition or, for that matter, by the violent response to representational images that is a central feature of Anabaptist history? I am acutely aware, when I pose such questions, of the fact that I am a fish out of my own disciplinary waters. I also remember Blake’s words of warning: “To generalize is to be an idiot.” It is not my aim here to come up with some kind of ethnic recipe. Lured into interdisciplinary waters by my own ethnicity, however, I am venturing ahead because there are questions that seem to demand my attention.

While reading an interview with Wanda Koop, for example, I took notice when she commented on a “figurative undercurrent” in her work that she didn’t “allow to really happen until 1985.” Until that time, she said, “I avoided using figurative images . . . I would often paint figures in and then paint them out.” The interviewer, Robert Enright, asked the obvious question: “Why would you have suppressed that figurative impulse, even if unconsciously?” In reply, Koop speculated only that at the time it wasn’t “cool” to be “hot.” The question was left hanging there and there it still is, begging to be asked and to be historicized. Other questions follow. When Koop did begin to break through whatever it was that was suppressing the figurative, why did she make masks and mask-like faces – African, Chinese, hockey-masks? When I look at them consciously with “Mennonite” eyes, the decorative patterns seem to expose what they cover, conveying both desire and fear.

But what does it mean to look with “Mennonite” eyes? A second group of questions relates not to the work of specific artists but to what E.H. Gombrich called “the beholder’s share.” Do Mennonite ways of seeing visual art (or not seeing it) contain any residual influences from those long-ago iconoclastic scenes of destruction that shaped our identity – statues toppled, stained glass systematically smashed, icons demolished, cathedrals gutted? Since the social history of Mennonite attitudes to art has not been written, it is difficult to trace the historical roots of our way of seeing. My argument here will be based on my own honest responses to the works in question – how could it be anything else? Yet I am also trying to imagine a collective “Mennonite” response that is not identical with my personal way of looking. To deal with this dilemma I will put on, for purposes of this argument, the mask of the “Mennonite” spectator.

It is hard to define a negative, but our continuing resistance to visual art can be made visible if we contrast it with the collective Mennonite response to music. Gathie Falk is as famous in the area of the visual arts as Ben Heppner is in the area of music, but her name is not known by most Mennonites. The same community that has no problem with Wagner responds with hostility or indifference to the powerful images being made by our visual artists. To be fair, this difference in response and this suspicion of “difficult” abstract art is not unique to Mennonites and is partly the result of differences in the medium. In music the technology of reproduction is more “in tune with” the art; a recording may not be adequate but it is not hostile to what the artist is doing, and most of us have a large collection of such recordings.

The same is not true in the visual arts. Much recent visual art does not reproduce well and is prohibitively expensive in the original, yet it has to survive in a “culture dominated by pictures, visual simulations, stereotypes, illusions, copies, reproductions, imitations, and fantasies.” W.J.T. Mitchell notes that it is “a commonplace of modern cultural criticism that images have a power in our world undreamed of by the ancient idolaters.” He refers to this as a “modern, secular idolatry linked with the ideology of Western science and rationalism” and comments that the “real miracle has been the successful resistance of pictorial artists to this idolatry, their insistence on continuing to show us more than meets the eye with whatever resources they can muster.”[4]

I like to imagine that our decorative tradition helps our female artists to do their part in this miracle but if so, then it’s a David-and-Goliath confrontation in which the decorative folk tradition is not even David. It is just a small stone in the slingshot. The history and technology of western mimesis is Goliath, but unlike the Old Testament giant, this one is unkillable. While discussing her set of “five eight-foot square pared down hockey masks” with Robert Enright, Wanda Koop commented: “It’s a mass media culture, it’s a killer culture.”[5] I sometimes wonder if the long history of our own decorative tradition predisposes me to be attracted to the decorative folk traditions of other cultures. It makes sense, after all, that for a “people apart,” this would be one of the most visible bridges to an “other” culture. When Koop walked through Toronto’s Chinatown, she chose to buy paper cut-outs rather than landscape brush paintings.

On the basis of my own, albeit limited, viewing experience, I hypothesize that the “decorative” element in the work of our Mennonite artists helps them to work forcefully against the grain of mass media reproductions. Nicole Dubreuil-Blondin refers to the metaphysical baggage that has clung to representation and that has tied the pictorial sign to “a transcendent Real, or Subject.” It does seem to me that Mennonite women artists travel light in this sense. What Dubreuil-Blondin urges that artists do with an emphasis on the painterly, our artists seem to do with the decorative – and they do it as if it’s no sweat. This element of lightness and play combines with a decorative emphasis on the materiality of the medium to challenge the pretensions of transparency and transcendent meaning that can weigh down any work of art.[6]

If you turn from the decorative element in avant-garde art to the decorative objects themselves, the issues are further complicated by nostalgia. Quilts have come to be very highly valued among Mennonites as nostalgic collectors’ items, commanding increasingly high prices. Nostalgia supports an anti-intellectual view of art. The works I will consider below act instead as a catalyst for thought, and one of the questions they invite us to ask is, What is it that is covered up when quilts are used in this fetishistic way? David Freedberg speaks of the “myth of aniconism,” the myth “that there can be a culture that has no images of the deity at all.”[7] Mennonite cultures, being built on precisely that myth, tend (perhaps more than other groups) to construct a nostalgic, pseudo-aesthetic with the quilts.

I am not denying the beauty of the quilts, nor do I wish to denigrate the women who make them. On the contrary: I celebrate their work. Within a larger feminist perspective, our Mennonite foremothers are seen as part of a history of art that offers alternatives to the excesses of the mainstream western tradition. Within the decorative tradition, man is not the measure of all things. Flowers are just as important. There’s a welcome humility, also, in the unashamed acknowledgement within the decorative tradition of the way the art is limited by the need for thrift. Stencils, formulaic patterns, iron-on transfers, and many other aids are used. Our foremothers went quietly against the grain of centuries of western art history, using primitive technology to make anti-classical designs, working within the often severe economic and social conditions of their times. It was not only the restrictions deriving from theology but also the material conditions of their lives that led them to keep the decorative tradition alive. While the men were working to recover the Anabaptist vision, they worked to recover the rocking chair.

If we want to see the work made by the artists among us, however, we must resist what Susan Stewart has called “the social disease of nostalgia” which gives the past a fake authenticity and thus kills the present. Nostalgia, as Stewart notes, is “a sadness without an object . . . . the past it seeks has never existed . . . .” Hostile to history, it “threatens to reproduce itself” over and over again as “a felt lack.”[8] We need to historicize our response to art and to interrogate the assumptions that shape our experience of it. It should be possible to pay tribute to those thousands of Mennonite women who kept the decorative tradition alive through the centuries but to do so in a way that would, at the same time, open up connections between that tradition and the smaller but significant number of contemporary women artists. One way to do this would be to ask questions concerning power and the making of art that apply not only to quilts but also to contemporary art. Who makes it? Who buys it? Who controls the form, the price, the reception? If we pay attention, the works of our artists have a lot to teach us about these issues. I agree with Elaine Showalter that we must “deromanticize the art of the quilt, situate it in its historical contexts, and discard many of the sentimental stereotypes of an idealized, sisterly, and nonhierarchic women’s culture that cling to it.”[9]

In my slide-lectures on this topic,[10] I have used the metaphor of textile to visualize the opposition of the decorative and the mimetic, seeing them as the warp and woof of a fabric that may be tested by pulling first one way, then the other. At one stage, after too many nights spent reading martyrs’ tales, I convinced myself that I was hearing voices in the quilt.[11] I had in mind what Sophocles called the “voice of the shuttle,” the story of Philomela, whose tongue was cut out but who told the story of her rape by weaving a tapestry.

It was because Philomela was so good at making lifelike renderings that her sister could read the story in the tapestry. Such realistic representations of human figures are quintessential Hellenic examples of the thread of classic realism, and reflect the classical reverence for the human body and the value placed on the individual. Unlike geometric decorative patterns, representational images have a power to move the spectator. “People are sexually aroused by pictures,” notes Freedberg, “they break pictures . . . they mutilate them, kiss them, cry before them, and go on journeys to them; they are calmed by them, stirred by them, and incited to revolt. . . .”[12] Such responses, despite or because of our history, exist as much among Mennonites as in any other group. You have to have a powerful response to images to be willing to die in an effort to deny their power – or to wish for the death of the image-maker. In the book of comments at one of Koop’s exhibitions, a viewer wrote: “Wanda Koop should be hanged.” Not a pretty threat, but one illustrating Mitchell’s point that the various historical instances of iconoclasm (including the Anabaptist) reflect an ambivalence which is a constant feature of the human response to images.[13]

The complex psychology of this response is reduced in the Judaeo- Christian tradition by a theology which splits off the spirit from the body. St. Augustine defines idolatry as the “subordination of the true spiritual image to the false material one.”[14] We should be safe from the danger of idolatry, then, if we keep subordinating the material to the spiritual. The illusion of such safety is apparent in the pictures of martyrs with which most of us are familiar. Jan Luyken’s engravings for The Martyrs Mirror are an example of the comfort we still find in images of shared suffering. Representations of earlier Catholic martyrdoms often show a tavoletta, the comforting image of Christ, being held up to a man about to be executed. The stories that accompany these pictures are an example of what Mitchell calls “ekphrastic hope.” Ecphrasis is a rhetorical figure – meaning a verbal representation of a visual display – that seems to me particularly useful in accounting for Mennonite responses to art. Word and Image: it’s like a struggle for possession of the Mennonite soul. No wonder we need to escape into music. Sometimes, however, we allow ourselves to steal a look at the old engravings.

Mitchell expands the use of the word ekphrastic and this expansion suits my needs here. “Ekphrastic hope” is that moment when the beholder hopes to overcome the “otherness of visual representation”[15] and it is exemplified by Luyken’s engravings even though the martyrs do not hold tavolettas. This hope, however, is explicitly repudiated by the theology of the martyrdom. Theology would have us believe that the sacrifice and suffering that is apotheosized in these pictures results from a rejection of false material comforts and affirms a spiritual comfort. Anneken Hendriks, burned at Amsterdam in 1571, is represented by Luyken bound to a ladder that is about to be thrust into the flames. Her eyes gaze up past the billowing smoke to heaven and her hands point upwards in prayer. The image has an extra power because she is a woman. Eve tempted Adam with the things of this earth and caused the fall but even women – the picture seems to say – can on occasion rise to this high spiritual level.[16]

Ilse Friesen, noting examples of statues of crucified women, believes that they testify

to a tremendous religio-psychological need on the part of women for an image of extreme female suffering and ultimate iconic significance, something that was not met by the official iconography of the church.[17]

I would not by any means deny this need but would argue, again, that we should historicize it by recognizing that such iconophilia coexists with iconophobia. The Anabaptist in me remains wary of a tendency to idolatry. Does not the image of the woman suffering for not worshipping an icon, itself become an icon? If we are urged to imitate this woman’s faith and she, in turn, is an imitation of Christ, then how does this relate to Luyken’s imitation or mimesis? In the faces represented by Luyken there is a serenity, a gelassenheit, that we recognize and honour. Is this our golden calf?

It is a tribute to Jan Luyken’s art that he found ways of representing that allowed him to touch on these issues by showing the limits of representation. His engraving of the scene following the marytrdom of Maeyken Wens is an example [illustration on p. 35]. The caption for the picture reads: “Maeyken Wens was burned at Antwerp with a tongue screw in her mouth. Here her sons search and find the screw to keep in memory of their mother’s Christian witness, AD 1573.”[18] Maeyken’s son Adriaen, “aged about fifteen years,” is shown hunting among the ashes for the screw while his three-year-old brother looks on. This is literally a graven image, but the engraver has fractured it by trying to represent what cannot be represented. In so doing, he returns us to an awareness of materiality and of our mortality that is ironically comforting because we are the survivors. In this engraving Luyken refuses the representation of the martyr and leaves us with the orphans. The resulting image is not like the cross, a transparent sign leading to transcendental significance, but becomes opaque and troubling. Aware of the mother as a specter that haunts the site, we experience Verfremdung, our estrangement as spectators at a distance from the picture. The picture opens up a gap in which the beholder’s experience cannot be contained by theological dogma.

If you are a Mennonite beholder, you are probably protesting by now. It only seems to me that Luyken chooses to be with the children, you may be saying, because I am a mother. I, in turn, respond by arguing that just by making an engraving in copper, Luyken chooses to be a part of the very material world that is rejected by that theology. But the powerful subjective elements unleashed in our response to visual art have to be acknowledged as coexisting with our efforts to see objectively. Objectivity is never achieved, and what we are left with is coexisting and interwoven subjectivities. In taking up the position of spectator, each of us is distanced from the work of art. The act of looking works to collapse the split between subject and object, involving me as a kind of specter inside the work I am viewing.

Recognition of this self/other drama is crucial for the Mennonite spectator, I argue, because of our ethnocentric past and our suspicion of outsiders. James Elkins comments that “we need to believe that vision is a one-way street and that objects are just the passive recipients of our gaze in order to maintain the conviction that we are in control of our vision,” and that we who behold are autonomous, stable selves. We may all “want to be pictures to some degree” and it “may be that when we look at visual art we are seeing examples of that desire”[19] – a desire resembling what Mitchell calls “ekphrastic hope.” Since, however, we are not ordinarily conscious of that desire, there is a considerable shock when the picture offers us a kind of reflection that stares back at us.

This shock effect is what happened in Gathie Falk’s 1972 piece of multi-media performance art, “Red Angel,” which is recorded on video [illustration on p. 35]. Falk claims to have written this piece because she found an old white dress and had to think of something to do with it. “Red Angel” is constructed “like a rondo, with theme A followed by theme B, followed by theme A.”[20] It begins with Falk sitting on a red buffet. The body of the artist (inside that dress) is present in her own “painting,” staring back at the audience. The white dress resembles a wedding gown to which are attached enormous white wings (constructed out of foam rubber and chicken feathers). Five tables are positioned in front of the buffet, and each holds a turntable on which is a red apple on which is a red parrot. The parrots take turns singing the round “Row, row, row your boat” as the turntables turn. Falk is the last to join in and the last to finish. When the song is finished, the artist slowly takes off her white dress. Underneath, she is wearing a grey satin dress. An old-fashioned wringer washer is trundled onto the stage by a woman who takes the white dress from Falk, washes it, then leaves. After this the round song is performed again. The last voice heard is that of Falk herself, singing “Life is but a dream.”

In the multi-media art world of the 1960s and ‘70s, such experimental art perhaps seemed less bizarre than it does now, but there is no question that Falk’s performance works are a challenge for the spectator. “Ekphrastic hope” is a dream come true in an absurdly literal way. By her own account, Falk’s aim in her performance art was to contrast ordinary actions – like eating an egg or washing clothes – with “slightly exotic events such as shining someone’s shoes while he is walking backwards singing an operatic aria . . . sawing popsicles in half and using them as weapons of assault and defence . . . .”[21] The comedy of Monty Python or the poetry of Edward Lear come to mind, but they are not an adequate context to account for what is happening here. Not surprisingly, Falk’s bizarre juxtapositions have baffled many viewers. Does the “Mennonite” historical context help make sense of this? Falk’s membership in a small Mennonite church is often cited as if it might, but Mennonite tradition allowed decoration only when it was useful. Falk’s objects are not functional: a 1936 Ford coupe stuffed with ceramic watermelons won’t take you anywhere. Neither will a case of eight ceramic running shoes. Over a hundred bisque cabbbages hovering in the air won’t feed you. Falk’s objects are boldly and gleefully useless. They stand in sharp contrast to a comment Sandra Birdsell made somewhere that “Mennonites are engaged in a joyless search for meaning.”

The heterogeneity of Falk’s celebrated objects has not stopped critics from trying to label them Mennonite. In 1990, when she came to Toronto to accept the Gershon Iskowitz Award, John Bentley Mays, referring to the “unforgettable image of Gathie Falk sitting behind a row of shiny red parrots,” labelled her a “Mennonite artangel.” With a cavalier disregard for accuracy or historical context, Mays describes her “simple theatricals” as “bewinged, bedizened and sentimental as a Sunday School Christmas pageant” and pictures her as a school-teacher with “plain-jane bobbed hair . . . transfigured at last into the glamorous high-art angel of her dreams.” He then follows up this grotesque caricature with his own nostalgic idealization of her “Mennonite” qualities, claiming that “virtually all” her “quietly joyful works” were produced with “members of Falk’s Mennonite community in Vancouver, and performed by them as well.” As if there were not dance companies in Vancouver, Toronto, and New York ready and waiting to perform whatever she wrote during those heady days of multi-media happenings! Marshall McLuhan would dance in his grave for her. Her “Red Angel,” doing a striptease with a white dress over a grey dress, is all dressed up and ready to join in the transformations of Blake’s heaven and hell. Who needs Mennonites? Mays does not allow such facts to get in the way of his headlong rush towards a nostalgic utopia that really is no place.

In these performances, if only for a moment, there was peace on earth and freedom from the hungry games of power. There was the loveliness of cherishing ordinary things – from cabbages and eggs to old songs and old friends – as an act of religious gratitude and blessing, and the beauty of dwelling on the earth in the bonds of kindness.[22]

This absurd excuse for art criticism dramatizes what happens if the beholder denies his own ambivalent subjective response while straining for pseudo-objectivity. Mays, estranged by the technique, assumed that he must have stumbled into a Mennonite church, but Falk’s experiment in “Red Angel” has more profound implications than any Sunday School pageant. Her bodily entry into the otherness of the work of art is radically transgressive. Perhaps being Mennonite, one of the “people apart,” gave her the energy to repudiate separation.

That is speculation. What is more certain is that the Mennonite emphasis on music was an advantage, particularly at that time. When Robert Enright observed that Falk took to the form “like a duck to water during those Intermedia workshops given by Deborah Hay in 1968,” she pointed out that her training in “harmony and counterpoint and all that stuff” might have helped her.[23] Her funkiness is another story. “Funk art” is a phrase that was coined to describe the wacky artwork coming out of California in the late 1950s and ’60s. It is fascinating to speculate about the reasons why one of the most courageous examples of funk art in Canada was a Mennonite woman. Perhaps she is that rare creature: a Mennonite eccentric. Falk’s importance to Canadian art, in any case, now goes far beyond a sixties phenomenon and she has herself been “installed” in the canon of top Canadian artists. This would not have happened if her performances had really been a representation of “peace on earth.” More like the peace that shall destroy many, her work is of particular interest in relation to the work of younger artists coming out of Mennonite communities. By shattering boundaries, Falk opened up possibilities for ways of making that play, as did “Red Angel,” with the conflicting emotions of the Mennonite spectator.

Adriaen Wens hunts among the ashes for his mother’s tongue screw while his three-year-old brother looks on. Jan Luyken, Engraving. Used by permission of the Conrad Grebel College Archives

Gathie Falk, Red Angel, Performance, 1972. Photo by Chick Rice.

Lois Klassen, Household Lamps, 1988. Used by permission

Aganetha Dyck, The Glass Dress, from The Extended Wedding Party, glass and beeswax, 1998. Photo by Peter Dyck. Used by permission of the artist.

Lois Klassen’s “Household Lamps” is like an inside-out version of “Red Angel” – an uncanny illustration of a point made by James Elkins. Our eyes are designed to seek out “complete figures.” Even when faced with a smear, we automatically look for bodies and “instinctively repair fragments into wholes and search for continuous contours and closed curves.”[24] If we can’t see a body, we’ll make do with a face or a hand. Using the uniforms of the medical profession, Lois Klassen’s hands, following the work of her eyes, have shaped the outlines of the human form. The empty uniforms activate a spectator response that psychoneurologists call “subjective contour completion.” We prefer to see bodies and if we can’t have them, “we continue to see them as afterimages or ghosts.” Klassen has managed to suspend the viewer in that state of “ekphrastic fascination,” which turns the spectator into a specter hovering between hope and fear. The spectator’s projection into this body expresses a longing, a hope for “the transformation of the dead, passive image into a living creature.” The moment of fear comes when we recoil, as we do in Luyken’s engraving of Mayken Wens’s orphans, from the possibility of such a unity:

All the goals of ‘ekphrastic hope,’ of achieving vision, iconicity, or a ‘still moment’ of plastic presence . . . become, from this point of view, sinister and dangerous . . . . All the utopian aspirations of ekphrasis – that the mute image be endowed with a voice . . . all these aspirations begin to look idolatrous and fetishistic.[25]

In “Red Angel,” Gathie Falk braved “ekphrastic fear” by entering the image and filling it with her own voice. In “Household Lamps,” Lois Klassen represents the image as empty vessel so that in trying and failing to enter it we become aware of our desires and fears. Moreover, because the vessel may be filled with artificial light at the flick of a switch, Klassen locates this experience in the technological place where we all live.