Articles

Book Reviews | Full Book Review Section (PDF)

Foreword

Special lectures mark this issue of The Conrad Grebel Review, which is largely devoted to the work and thought of noted American theologian Stanley Hauerwas, who is the Gilbert T. Rowe Professor of Theological Ethics at Duke Divinity School in Durham, North Carolina. We take pride in presenting lectures given by Hauerwas at Conrad Grebel University College in March of this year. The two addresses on Dietrich Bonhoeffer constituted the 2002 Bechtel Lectures, a recently established series named in honor of donor Lester Bechtel.

These lectures and several related pieces, all skillfully introduced by James Reimer, comprise the “tribute to Hauerwas” section of this issue. Readers

will appreciate Reimer’s personal perspective and his insights into the deeper, “grain of the universe” aspects of Hauerwas’s theology.

In a different — but, we think, complementary — vein we offer another

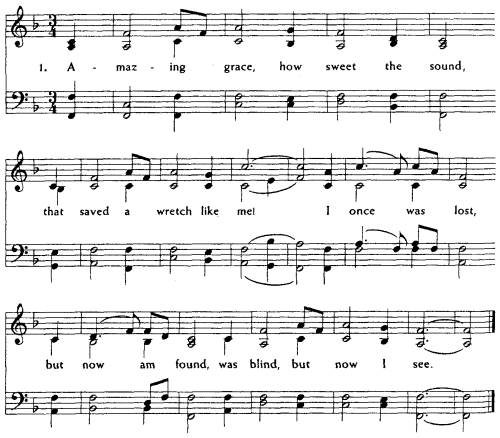

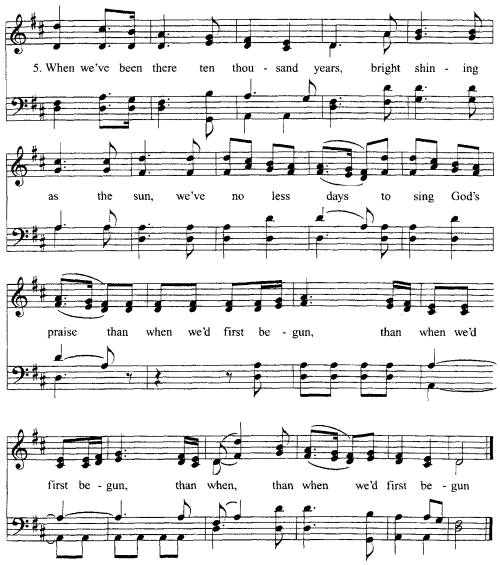

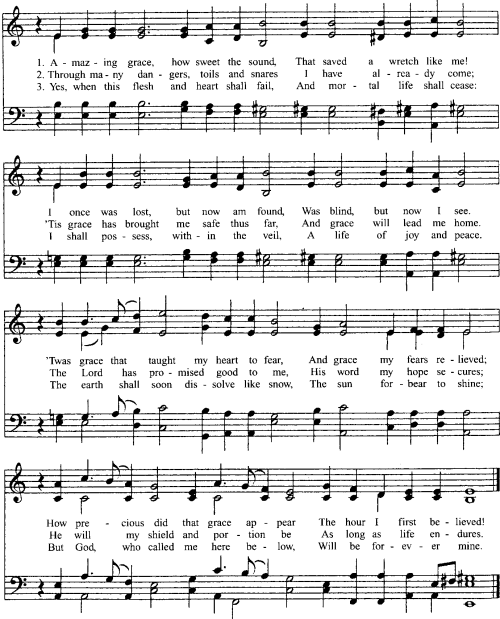

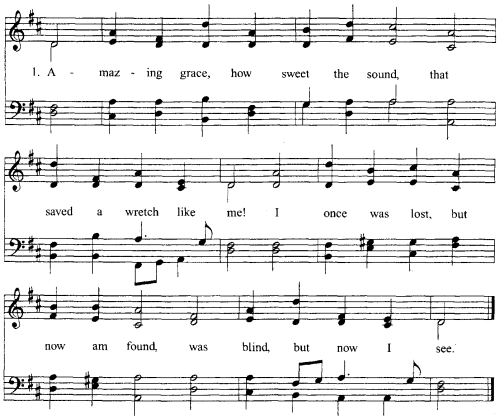

special address, the sixteenth annual Benjamin Eby Lecture, given in October 2001 by Kenneth Hull, an associate professor of music and director of the Institute for Worship and the Arts at Conrad Grebel University College. Hull explores “Text, Music, and Meaning in Congregational Song,” using the familiar hymn “Amazing Grace” to illustrate the dynamic interaction of text and music.

For a diversion from all these lectures, if you need one, we provide a

spate of book reviews as well, covering recent releases in Biblical studies,

history, and other subjects.

This issue of the Review also sees a change in personnel. After five years as the journal’s editor, Marlene Epp has relinquished that role in order to devote herself to administrative and academic duties at Conrad Grebel University College, where she serves as Academic Dean. Arnold Snyder, the Review’s former editor, has returned as academic editor, while I have taken over as managing editor. Hildi Froese Tiessen continues as literary editor, Arthur Paul Boers as book review editor, and Carol Lichti as circulation manager. (Special thanks to Lauren Anderson for tape transcription for this issue.)

All of us on the Review’s production team appreciate the support offered

by our authors, peer reviewers, book reviewers, subscribers, and readers. We look forward to continuing and enhancing our association with you as our journal enters its third decade of publication. We welcome manuscripts from members of the Anabaptist-Mennonite Scholars Network — and equally from other writers and researchers — who share our interest in thoughtful, sustained discussion of spirituality, ethics, theology, and culture from a broadly-based Mennonite perspective.

Stephen A. Jones, Managing Editor

The Conrad Grebel Review 20, no. 3 (Fall 2002)

I

This issue of The Conrad Grebel Review is devoted largely to lectures given by Stanley Hauerwas at Conrad Grebel University College in Waterloo and at Toronto Mennonite Theological Centre on March 14-15, 2002. The overall theme of the series was “Bonhoeffer, Yoder, and political ethics.” In Toronto Hauerwas lectured on “Bonhoeffer as a political theologian,” and was responded to by Fred Shaffer (a Knox College doctoral student in theology), Pamela Klassen (religious studies professor at the University of Toronto), and Craig Carter (Dean of Tyndale College, Toronto). This first lecture, together with responses by Shaffer and Klassen, appear below. Hauerwas repeated this lecture in Waterloo and gave a second lecture there, “Bonhoeffer on truth and politics,” which also appears below. Hauerwas is at his most delightful and outrageous when he departs from his text, allows his mind to spin into tangential ramifications of what he has just said formally, or talks more informally and unguardedly in question-and-answer situations. One such occasion was a noonhour

meeting with faculty and friends of Conrad Grebel University College

and the University community. There we encountered a rich, extemporaneous Hauerwas reflecting about his life and thought and the various personalities and movements that have influenced him. This discussion appears in edited and shortened form below.[1]

In his first lecture, Hauerwas says that although “This is the first essay

I have ever written about Bonhoeffer, . . . it is certainly not the first time I have read him.” In fact, he says, “I first learned what I think from reading Bonhoeffer (and Barth).” The other thinker who had an equally important influence on him is John Howard Yoder. Bonhoeffer’s The Cost of Discipleship, he contends, prepared the way for his later reading and reception of Yoder’s The Politics of Jesus. The reason that Hauerwas did not write on Bonhoeffer earlier was to avoid being identified either with what he considered a misinterpretation of Bonhoeffer’s later Letters and Papers from Prison by the “death of God” theologians of the 1960s or with Joseph Fletcher’s reading of Bonhoeffer’s Ethics as a form of “situation ethics.” Hauerwas is now, finally, acknowledging “a debt long overdue.”

Another reason Hauerwas hesitated so long to publicly appropriate Bonhoeffer’s theology was that as a pacifist he had difficulty understanding, let alone accepting, the German theologian’s involvement in the conspiracy to kill Hitler. The first part of Hauerwas’s lecture is a wonderful summary of the life of Bonhoeffer leading up to his conspiratorial activities, his arrest for “subversion of the armed forces,” and finally his death by hanging on April 9, 1945 on Hitler’s personal order. The greatness of Bonhoeffer lies in the fact that his life and thought, faith and action, theology and politics could never be separated. We may disagree with his final choices, but his martyrdom, if one can call it that, followed ineluctably from how he had lived and from what he had taught and written. What makes Bonhoeffer’s theology so congenial to Mennonites, and so similar to Yoder’s thought, is his ecclesiology. Departing from traditional Lutheran two-kingdom theology, Bonhoeffer (and Hauerwas)

makes the church as Christ’s concrete, visible community of discipleship the keystone of his whole theology. Already in his first book, Sanctorum

Communio, Bonhoeffer describes the church in theological-sociological terms as Christ’s ongoing presence in history. His theology was a frontal attack against the Protestant liberal (including the Pietist) accommodation of the church to the world—its attempt to justify Christianity to the present age.

It is when Bonhoeffer attempts to offer a positive theology of social

and political institutions (as “orders of preservation” or “mandates” rather

than the prevalent Lutheran “orders of creation”) that Hauerwas contends

Bonhoeffer does not go far enough in distinguishing himself from Lutheran

two-kingdom thinking, although he was probably moving in that direction

when he proposed an “Outline for a Book,” which he never got to write

because of his premature death.

While the first lecture leaves us thinking that in the end Bonhoeffer’s

life may have been more politically engaged than his theology, Hauerwas’s

second lecture attempts to rectify this by exploring a theme rarely considered in Bonhoeffer studies: lying, deception, and truth in politics. Hauerwas’s thesis is that when in the political process compromise rather than truth-telling (especially in democratic regimes) becomes the primary end, then “politics abandons the political realm to violence.” One of the most significant political contributions that the Christian church can thus give to society is the witness to truth and the refusal to lie. What Bonhoeffer found most disturbing about his experience in America in 1930-31 was the tendency to subordinate truthtelling to upholding fairness and community. Tolerance of diverse opinions, rather than confessional and creedal truth claims, becomes normative, a tolerance which leads to indifference and finally to cynicism and violence, despite its rhetoric of peace. Without truth-telling there can be no peace or justice in any social order, and for both Bonhoeffer and Hauerwas, “Only the peace of God [in which forgiveness of sins is the essence] preserves truth and justice.”

This is no “situational ethic.” Joseph Fletcher had it wrong. True, Bonhoeffer did say that the particular context has a bearing on what it means to tell the truth in a given situation, but what he tried to convey is that truth is never an abstraction; it must always be a living truth that is true to concrete reality. As such, telling the truth requires skill and must be learned, an insight that is consistent with Hauerwas’s narrative understanding of the church as a community of spiritual and moral formation (a virtue ethic that depends on developing habits of right thinking and acting within the context of a community). The caveat is that since the Fall, being truthful sometimes requires secrecy and reticence. When public language becomes debased, as in National Socialist Germany, and the various orders of life get confused (family, labor, nation, state, church), words become untrue. Therefore, speaking the truth in such an

age of “organized lying” (Hannah Arendt’s term) means ultimately witnessing to the truth by living it, and “living the truth” requires the existence of “a community . . . that has learnt to speak truthfully to one another,” one that knows “that to speak truthfully to one another requires the time [and patience] granted through the work of forgiveness.” This is the church as Jesus Christ present in history.

II

I have undergone three conversions in my life, and the third of them has

brought me — reluctantly — to the distinctive Barthian “‘natural’ theology”

of Hauerwas.

1) Conversion One. My first conversion followed very closely the pattern

Hauerwas describes in his autobiographical reflections printed below.

Hauerwas’s experience as an evangelical Methodist in the American South

and mine as an evangelical Mennonite in Southern Manitoba must have been quite similar, except that my attempt to get saved by answering the altar call in numerous revival meetings, conducted by both Mennonite and non-Mennonite evangelists, took place against the backdrop of a religious, cultural, and ethnic minority group that lived on the periphery of mainstream culture.

This minority group had lived in relatively well-defined communities for almost 500 years with its own language (my first language was low German), its own schools (private schools where the German language and religious education was part of the curriculum), its own culture (music festivals where young people were nurtured in both religious and folk music); a mixture of Dutch, German, and Russian cuisine celebrated in its cookbooks; village life with house-barns where people performed rituals that come with such small rural communal existence; and its own religious tradition (going to church on Sunday, listening to sermons both in German and English, learning the catechism with its 200-odd questions and answers as a condition for baptism as a 16-year-old upon a personal confession of faith — a catechism and confession that was orthodox in all its basic tenets with additional weight on a transformed life of discipleship, including the rejection of all participation in war and violence). Church was the most important, but not the only, aspect of this people’s existence.

Although a personal confession of faith had been central to the Mennonite

religious experience, a more individualistic, subjective American evangelical

emphasis on personal conversion was something relatively new, and it came hand-in-hand with assimilation and the “liberalizing” of Mennonite language, education, culture, and theology, playing a significant role in the break-up of Mennonite communal existence. This highly personal, existential experience of salvation — like Hauerwas, I could never get it quite right — left a profound imprint on how I think about God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit. It is something which I still value deeply and wish I could pass on to my children in one form or another. It was the primary impulse that led me to study theology at college. Later, however, I realized that what I learned at university in the form of liberalism (the historical critical method, Feuerbach, Freud, Marx) — which I now considered to be a radical critique of my earlier “evangelical” experience — was in many ways the logical outcome of the subjectivism and experientialism of revivalism, and ultimately a threat to all traditional, communal authority structures.

2) Conversion Two. Discovering the historic communal roots of my own tradition was the beginning of the second conversion. It was only the

beginning, and partial at that, for the Anabaptism that I first discovered thought of our sixteenth-century historical and theological forebears as the harbingers of modernity and democratic liberalism. For Harold S. Bender, the fundamental democratic assumptions of the modern world — freedom of conscience, separation of church and state, voluntarism in religion: presuppositions “so basic in American Protestantism and so essential to democracy” — are ultimately “derived from the Anabaptists of the Reformation period, who for the first time clearly enunciated them and challenged the Christian world to follow them in practice.”[2] Most recently Mennonite Islamic scholar David Shenk has argued even more strongly: “As a minority movement, the Anabaptists shattered the state church system, and opened Europe to pluralistic cultures and religious freedom. A century later the philosophers of the Enlightenment picked up these Anabaptist themes of personal freedom and choice and applied them to the philosophical foundations for modern democracy. But it was the Anabaptists who led the way in transforming Europe forever. By insisting on adult baptism they were blazing the way forward for the global commitments today to human rights, religious freedom, and pluralistic culture. The ‘powerless’ and persecuted Anabaptists practiced freedom of religion within Christendom, thereby beginning the process that has resulted in transforming Christendom into societies where freedom to believe or not to believe is a deeply held commitment.”[3] For Shenk, this liberal, democratic understanding of pluralism is a happy historical development essential to inter-faith dialogue.

This second conversion was completed with my discovery of the “poverty of liberalism,” by reading neo-Marxist critical theorists of the Frankfurt

School but, most decisively, by my encounter with the person and thought of the late Canadian Christian philosopher George P. Grant. There I found the first powerful, intelligent defence of the classical conservative vision, including both Greek Platonic-Aristotelian and Judeo-Christian thought, both of them having more in common with each other than with either modern or postmodern thought — namely, that there is an eternal horizon within which history and human action takes place and receives its meaning and moral import. Although I have come to see the shortcomings in Grant’s historical pessimism, his analysis continues to influence my critical reading of contemporary theology, including that of Barth, Yoder, and Hauerwas. They still strike me in some ways as too liberal, and too western. Grant has also influenced my reading of Anabaptist sources and Mennonite history.[4] Reading Grant has convinced me not only of the poverty of liberalism but the inadequacy of all forms of historicism, including certain forms of narrative that appear to make time as history the primary theological category. Essential to the classical vision is a realism that holds to the reality of invisible universals — an invisible eternal horizon, whether comprehended in terms of Platonic ideal forms or in the dynamic relations of the immanent Trinity, which is the transcendent basis of all historical particulars. In my view, contemporary theologies that collapse the immanent and economic Trinities fall into a historicism in which inevitably not all historical moments can be considered equidistant from God. For me, such equidistance is a sine qua non. This is why I am a reluctant convert to the “natural theology” of Hauerwas.

3) Conversion Three. I am a reluctant convert to Hauerwas’s natural

theology for both formal and material reasons. Formally, I love the freedom

with which Hauerwas does theology. He pays little heed to the niceties of

academic and church life, loves to burst the bubbles of established arrogance and presumption, without ever sparing himself — all in the service of what he considers to be theology’s fundamental task: to give witness to Jesus Christ and his church. His most strident critique is aimed at the pretensions of neutrality found in modern liberalism and pluralism, with its not-so-hidden assumptions about universal reason, freedom, democracy, equality, peace, and justice that are in fact linked to violence. He is a fearless, aggressive, and militant pacifist, one of the few dominant American theologians to speak out clearly against the “war on terrorism” presently conducted by his own country. I admire the freedom and courage with which he witnesses to the Gospel of peace and nonviolence.

III

Materially, I’m a reluctant convert to the substance of Hauerwas’s theology. Hauerwas has written innumerable occasional articles, authored, co-authored, and edited many books,[5] but his most recent monograph, his 2001 Gifford Lectures With the Grain of the Universe: The Church’s Witness and Natural Theology, is where one has to turn in order to wrestle with the depth of his theology.[6] In the introductory chapter Hauerwas says he will be proposing a theologically-based natural theology. This is a surprise for those who had thought that he, along with Barth and others, was against all natural theologies. In fact, Hauerwas claims Barth and even Thomas Aquinas as allies in his proposal. The natural theology that Hauerwas develops claims that theology knows and witnesses to the way things really are. Hauerwas relies heavily on Yoder’s way of doing theology, including Yoder’s assertion that “It is that people who bear crosses are working with the grain of the universe . . . . One does not come to that belief by reducing social processes to mechanical and statistical models, nor by winning some of one’s battles for the control of

one’s own corner of the fallen world. One comes to it by sharing the life of

those who sing about the Resurrection of the slain Lamb.” There can be no

deeper reality than cross and resurrection, and this reality is known only

theologically — that is, in the revelation of Christ.

Another surprise is that Hauerwas parts company here with his philosophical compatriot Alasdair MacIntyre, for whom philosophy is independent of theology and helps to prepare the way for it. Aquinas, says

Hauerwas, would not recognize such a natural theology, in which philosophical reason creates an apologetic foundation for subsequent “confessional” claims. The rest of the book shows how two previous Gifford lecturers, William James and Reinhold Niebuhr, had it wrong, and a third, Karl Barth (along with Aquinas), had it right, and ends with a conclusion in which Pope John Paul II and Yoder find themselves in the same camp. Here we have another instance of the wonderful freedom with which Hauerwas theologizes and breaks conventional stereotypes.

William James seeks to make a case for religion psychologically and

phenomenologically for people living within modernity, “an expression of pietistic humanism” for which Hauerwas has little sympathy. Hauerwas does have some affinity for James’ pragmatism in which “will” and “belief” are “shaped by passion-formed habits,” and the world and existence has an “unavoidable moral character.” But James’s understanding of the religious sensibility as “primordial” and of fundamental theological claims as “over-beliefs” gives Hauerwas much trouble. Essential Christian doctrines, like the Trinity or Creation, are of no value in James’s apologetics. For James, our religious experience, not the objective reality of that to which our experience refers, is critical. Prayer, for instance, is the soul of religion, but whether God exists or not is irrelevant; what is important is the subjective experience of prayer. The truth of theological ideas, in James’s pragmatic account, depends entirely on their relation to other

ideas and their functional value in concrete life. God is real because he produces certain effects. This particular critique by Hauerwas is exceptionally important, because the narrative school of theology, of which Hauerwas is a member, has sometimes been interpreted as making truth claims dependent on internal coherence, self-referentiality, and livability. This misunderstanding of his theology Hauerwas strongly disavows later on in the volume.

According to Hauerwas, William James displaces Christianity with American liberal democracy: James “thinks democracy is not just a social and

political arrangement but the very character of the emerging universe.” Not the cross and resurrection but modern, liberal, democratic values are the “grain of the universe.” What is most chilling about this prospect, and what some Mennonites have not realized who claim that Anabaptism is the forerunner of essential aspects of modernity, is that democracy as envisioned in the American experience needs violence to sustain itself. Hauerwas persuasively shows how the privatized religiosity that James espoused and identified with liberal democracy pushes Christianity to the edges and in effect condones violence. James thought that the coercion and violence necessary to sustain a democracy — for example, the freedom to overcome poverty and accumulate and protect capital — could also be relegated to the edges of society. If Hauerwas is correct, then Mennonites who claim that they and their Anabaptist forebears are the harbingers of modern liberal values find themselves supporting a strange

antinomy: lauding the dominant assumptions of modernity while rejecting the violence intrinsic to it.

In Hauerwas’s view, Reinhold Niebuhr’s 1939 Gifford Lectures, The Nature and Destiny of Man, are “but a Christianized version of James’s account of religious experience.” Niebuhr believed that Christian claims must be validated by science and experience — that is, tested by generally accepted empirical and rational norms, and by their ethical ramifications. He was a great preacher, but his congregation was “a church called America.” He too was a Jamesian pragmatist, one who tests the truth of theological ideas by whether and how they work. Religious supernaturalism and metaphysics (ancient creeds and dogmas) are not objectively true; their truth as permanently valid myths (Niebuhr’s version of James’s over-beliefs) resides only in their ability to illumine human experience. Theology is “first and foremost an account of human existence,” and talk about God is “but a disguised way to talk about humanity.” Hauerwas puts Niebuhr, James, Troeltsch, and contemporary Chicago ethicist James Gustafson in the same camp when he describes them as sharing the view “that there is no purpose other than the purpose that humans are able to impose on purposeless ‘nature.’”

The one doctrine that was so central to Niebuhr’s anthropology and that allegedly distinguished him from Protestant liberalism was that of “original

sin.” On this basis Niebuhr tries to develop a natural theology. “Niebuhr’s

project,” says Hauerwas, “is to provide an account of the human condition

that is so compelling that the more ‘absurd’ aspects of ‘orthodox Christianity’ — such as the beliefs that God exists and that God is love — might also receive a hearing.” Hauerwas does not question Niebuhr’s deep faith in the God of Jesus Christ, but in the end “the revelation that is required for us to know Niebuhr’s god is but a reflection of ourselves.” Christ’s death on the cross reveals God’s love in a way that transcends history; his life and death are symbolic for the divine agape, “the perfection of love as self-sacrifice.” But it is a cross and a self-sacrificial love that characterizes human existence as such and is our destiny. For Niebuhr God, even when described in trinitarian terms, is little more than the name for the human need to believe in the

ultimate unity and coherence of reality transcending the world of chaos.

The critical consequence of this is how it affects Niebuhr’s ethics: one has to accept the way things are because that’s the way they have to be. Niebuhr’s view of justice as “the most equitable balance of power” was a perfect match for the world following World War II. While the Christian love

of God and love of neighbor are not counsels of perfection for a few but the ideal for all, because of sin, self-sacrificial love is never possible when a third person is involved, where justice requires the balancing of interests, best negotiated in a democracy. Like James, Niebuhr “assumes democracy, and in particular American democracy, is the political system that most perfectly exemplifies ‘justice’ so understood.” Justification by faith is the heart of Niebuhr’s ethics. Loosed from its Christological basis, it frees humans to act in a fallen world. The church as an alternative community, while perhaps a sociological necessity, was never an epistemological or ethical necessity for him. In the end Niebuhr was “a theologian of a domesticated god capable of doing no more than providing comfort to the anxious conscience of the bourgeoisie.” Hauerwas is even more critical of Niebuhr than of James because Niebuhr, like a Trojan horse, enters the inner sanctum of Christian theology and debases its very language explicitly to support a world of violence.

The hero of With the Grain of the Universe is Karl Barth. In a remarkable

twist of argument, Hauerwas presents Barth as the true rationalist and natural theologian, one who represents a frontal attack against the irrationalism so prominent in his time. Barth becomes the stellar apologist for how the world is to be understood, and differs dramatically from James and Niebuhr. Hauerwas, though, is not an uncritical Barthian. Barth is not sufficiently catholic in his view of the church and never adequately explains “how our human agency is involved in the Spirit’s work.” Barth correctly saw that when theology is done as liberals do it, including James and Niebuhr, then Feuerbach is right. Feuerbach claimed that Christian doctrines are but expressions of human experience — projections and wish-fulfillment. Christians can counter Feuerbach only by claiming that God was objectively, historically, and specifically revealed in Jesus Christ. General revelation can never be the basis of special revelation, but special revelation (divine grace in all of nature as manifested in Christ) must always be the starting point for general or natural theology.

Although Hauerwas seeks to let Barth speak for himself, he makes Barth look like the founding member of the recent narrative school of thought

associated with thinkers like Hans Frei and Hauerwas himself. Barth’s Dogmatics is a compelling “story” that can only be narrated, not a system of thought that can be described; it is a “nonfoundationalist” account (there is no place outside of theology from which one can begin to do theology). I can’t help wondering, however, whether Barth would not have considered some directions taken by postmodern non-foundationalists like George Lindbeck as the logical outcome of modernity. Hauerwas indirectly recognizes this when he points out the surprising similarity between the Thomistic understanding of analogia entis (the analogy of being) and Barth’s analogia fidei (analogy of faith). Barth’s Dogmatics is a great theological metaphysics and ontology that is intrinsic, not extrinsic, to theological speech. At the heart of this natural theology is ethics — not a reduction of theology to ethics as in postmodernity but ethics grounded in the very trinitarian character and activity of God. Christian ethics is neither self-justifying, self-referential, nor a disguised form of humanism, but a witness to “the God who is the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” This witness, and any rational argument that accompanies it, is itself the work

of the Holy Spirit. This witnessing happens in the context of believing communities, of which the martyrs are the most powerful evidence.

Hauerwas concludes his tour de force with a tribute to the influence of John Howard Yoder, and makes the surprising claim that Yoder and Pope

John Paul II have much in common. He in effect “catholicizes” Yoder. It is this move that finally makes me a “reluctant convert” to Hauerwas’s theology, for it is the catholic element that I had always found missing in Yoder and his followers. Now I have reluctantly to re-think this assumption. For Yoder, as for the Pope, nonresistance and non-violent love are grounded in the very character of God as revealed in C hrist. “The relationship between the obedience of God’s people and the triumph of God’s cause is not a relationship of cause and effect,” says Hauerwas, “but one of cross and resurrection.” For John Paul II, Jesus Christ and the cross too are the center of history and the universe. In fidelity to this

Christ he calls on states not to make war, not to kill, and he offers the church as an alternative to the world of violence and to the “culture of death.”

Hauerwas contends that the Pope is even more radical than Yoder: “Yoder’s position . . . pales in comparison to the stance John Paul II takes

toward philosophy in his encyclical Fides et Ratio, though just how radical

the pope’s stance is may not be apparent immediately.” The Pope honors

philosophy as a discipline but forcefully argues that philosophical truths must be tested by the truths of revelation, “for the latter is not the product or consummation of arguments devised by human reason but comes to us as the gift of the life of Jesus Christ. That gift gives purpose to the work of reason by stirring thought and seeking acceptance as an expression of love.” In the remarkable denouement of the Gifford lectures, Hauerwas appears to be suggesting that Athens and Jerusalem converge in a grand natural theology after all — a christology-based natural theology of the Alexandrian type.

Good, but how is this natural theology to be mediated historically? This is precisely where Bonhoeffer had problems with Barth. For Barth special revelation was pure “act.” Bonhoeffer thought this act was mediated historically through the “being” of the church. For all his emphasis on the centrality of the church, it is not clear how, for Hauerwas, ecclesiology in its actual concrete, institutional form is a witness to the kind of natural theology he envisions. What distinguishes Pope John Paul II and Thomas Aquinas from Karl Barth and John Howard Yoder, surely, is their doctrine of the church and its mediating role in the world. In this regard we are left wondering at the end of the Gifford lectures. A serious consideration of this issue would lead us into the world of pneumatology in addition to christology, and into the differences between the Eastern and Western understanding of the role of the Spirit in the church, the world, and the cosmos, with profound ramifications for how we perceive natural theology.

Notes

[1] For a more detailed account of his lectures, see my “Provocative theologian lectures on Bonhoeffer,” in Canadian Mennonite (April 22, 2002): 29.

[2] Harold S. Bender, The Anabaptist Vision (Scottdale: Herald Press, 1944), 4.

[3] David Shenk, “Pluralistic Culture and Truth.” Unpublished paper presented at the “Shi’i-Muslim and Mennonite-Christian Dialogue,” Toronto Mennonite Theological Centre at the Toronto School of Theology, October 24-26, 2002. Used with permission.

[4] For more on Grant’s influence on my thought, see my Mennonites and Classical Theology: Dogmatic Foundations for Christian Ethics (Kitchener: Pandora Press, 2001), Part I.

[5] For an excellent selection of his writings and a comprehensive bibliography, see The Hauerwas Reader: Stanley Hauerwas. Edited by John Berkman and Michael Cartwright (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2001). [See review in this issue.]

[6] With the Grain of the Universe: The Church’s Witness and Natural Theology. Being the Gifford Lectures Delivered at the University of St. Andrews in 2001 (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2001). Quotations in this section are all from this book.

The Conrad Grebel Review 20 no. 3 (Fall 2002)

The Fragments That Were Bonhoeffer’s Life and Work

The primary confession of the Christian before the world is the deed which interprets itself. If the deed is to have become a force, then the world itself will long to confess the Word. This is not the same as loudly shrieking out propaganda. This Word must be preserved as the most sacred possession of the community. This is a matter between God and the community, not between the community and the world. It is the Word of recognition between friends, not a word to use against enemies. This attitude was first learned at baptism. The deed alone is our confession of faith before the world.[1]

So wrote Dietrich Bonhoeffer in 1932 just before the German Church’s struggle with Hitler began. This may seem an odd passage to begin an essay on Bonhoeffer’s political theology, but it is so only if one assumes a distinction can be made between Bonhoeffer’s theology, at least his early theology found in Sanctorum Communio and Act and Being, and his later involvement with the Abwehr [Military Intelligence Department] plot against Hitler. Indeed, it will be the burden of my account of Bonhoeffer’s life and theology to show that from the very beginning Bonhoeffer was attempting to develop a theological politics from which we still have much to learn.[2] He may have even regarded Sanctorum Communio and Act and Being as his “academic theology,” which no doubt they were, but I will argue that the theological position he took in those books made the subsequent politics of his life and work inevitable.

Anyone who has read Eberhard Bethge’s Dietrich Bonhoeffer: A Biography knows it is impossible to distinguish between Bonhoeffer’s life and work.[3] Marilynne Robinson uses the passage above to challenge those who think the consistency and significance of Bonhoeffer’s theology is given a prominence it might not have due to his courageous political activity and

death.[4]It is no doubt true that Bonhoeffer’s fame as well as his theological significance were attributed to his unfinished Ethics and his Letters and Papers From Prison. Many, quite understandably, interpreted some of Bonhoeffer’s own remarks in his prison correspondence to suggest his political opposition to the Nazis had occasioned a fundamental shift in his theology.[5] I will try to show, however, that Bonhoeffer’s work from beginning to end was the attempt to reclaim the visibility of the church as the necessary condition for the proclamation of the gospel in a world that no longer privileged Christianity. That he was hanged by the personal order of Heinrich Himmler on April 9, 1945 at Flossenbürg Concentration Camp means he has now become for those who come after him part of God’s visibility.

I am aware that some people reading my account of Bonhoeffer and, in

particular, my emphasis on his ecclesiology for rightly interpreting his life and work, will suspect my account sounds far too much like positions that have become associated with my own work. I have no reason to deny that to be the case, but if it is true it is only because I first learned what I think from reading Bonhoeffer (and Barth). This is the first essay I have ever written on Bonhoeffer, but it is certainly not the first time I have read him. I am sure Bonhoeffer’s Discipleship, which I read as a student in seminary, was the reason some years later John Howard Yoder’s The Politics of Jesus had such a profound influence on me.[6] Both books convinced me that Christology cannot be abstracted from accounts of discipleship or, put more systematically, we must say, as Bonhoeffer says in Sanctorum Communio, “the church of Jesus Christ that is actualized by the Holy Spirit is really the church here and now.”[7] The reason I have not written on Bonhoeffer has to do with the reception of his work when it was translated into English. The first book by Bonhoeffer usually read by English readers was Letters and Papers from Prison. As a result he was hailed as champion of the “death of God” movement and/or one of the first to anticipate the Christian celebration of the “secular city.”[8] On the basis

of Bonhoeffer’s Ethics, Joseph Fletcher went so far as to claim him as an

advocate of situation ethics.[9] As a result I simply decided not to claim

Bonhoeffer in support of the position I was trying to develop, though in fact he was one of my most important teachers. That I write now about Bonhoeffer is my way of trying to acknowledge a debt long overdue.

One other difficulty stood in the way of my acknowledging the significance of Bonhoeffer for my work: his decision to participate in the plot to kill Hitler seemed to make him an unlikely candidate to support a pacifist position. How to understand Bonhoeffer’s involvement with the conspiracy

associated with Admiral Canaris and Bonhoeffer’s brother-in-law, Hans von

Dohnanyi, I think can never be determined with certainty. Bonhoeffer gratefully accepted von Dohnanyi’s offer to become a member of the Abwehr because it gave him the means to avoid conscription and the dreaded necessity to take the oath of loyalty to Hitler. There is no doubt Bonhoeffer knew the conspiracy involved an attempt to kill Hitler. In spite of his complete lack of knowledge of guns or bombs he offered to be the one to assassinate Hitler. Yet the secrecy required by the conspiracy means we do not have available any texts that could help us know how Bonhoeffer understood how this part of his life fit, or did not fit, with his theological convictions or his earlier commitment to pacifism.[10]

That we cannot know how he understood his participation in the attempt

to kill Hitler and thus how his whole life “makes sense” is not a peculiarity

Bonhoeffer would think unique to his life. The primary confession of the

Christian may be the deed which interprets itself, but according to Bonhoeffer our lives cannot be seen as such a deed. Only “Jesus’ testimony to himself stands by itself, self-authenticating.”[11] In contrast, our lives, no matter how earnestly or faithfully lived, can be no more than fragments. In a letter to Bethge in 1944 Bonhoeffer wrote:

The important thing today is that we should be able to discern from the fragments of our life how the whole was arranged and planned, and what material it consists of. For really, there are some fragments that are only worth throwing into the dustbin (even a decent “hell” is too good for them), and others whose importance lasts for centuries, because their completion can only be a matter for God, and so they are fragments and must be fragments — I’m thinking, e.g. of the Art of Fugue. If our life is but the remotest reflection of such a fragment, if we accumulate, at least for a short time, a wealth of themes and weld them into a harmony in which the great counterpoint is maintained from start to finish, so that at last, when it breaks off abruptly, we can sing no more than the chorale, “I come before thy throne,” we will not bemoan the fragmentariness of our life, but rather rejoice in it. I can never get away from Jeremiah 45. Do you still remember that

Saturday evening in Finkenwalde when I expounded it? Here, too, is a necessary fragment of life — “but I will you your life as a prize of war.”[12]

However, thanks to Bethge’s great biography, we know the main outlines

of Bonhoeffer’s life. Bethge’s work makes it impossible to treat Bonhoeffer’s

theology apart from his life. Therefore I must give some brief overview of his life, highlighting those aspects of it that suggest his passion for the church. Yet I must be careful not to make Bonhoeffer’s life appear too singular. In a letter to Bethge in 1944, Bonhoeffer observed that there is always a danger that intense and erotic love may destroy what he calls “the polyphony of life.” He continues, “what I mean is that God wants us to love him eternally with our whole hearts — not in such a way as to injure or weaken our earthly love, but to provide a kind of cantus firmus to which the other melodies of life provide the counterpoint.”[13] Bonhoeffer’s life was a polyphony which his commitment to the church only enriched.

It is not clear where Bonhoeffer’s passion for God and God’s church came from. In a wonderful letter to Bethge in 1942 he confesses that “my resistance against everything ‘religious’ grows. Often it amounts to an instinctive revulsion, which is certainly not good. I am not religious by nature. But I have to think continually of God and Christ; authenticity, life, freedom, and compassion mean a great deal to me. It is just their religious manifestations which are so unattractive.”[14] Prison only served to confirm his views about religion. He writes to Bethge in 1943, “Don’t worry, I shan’t come out of here a homo religiosus! On the contrary, my suspicion and horror of religiosity are greater than ever.”[15]

The source of Bonhoeffer’s faith is even more mysterious, given his

family background. He and his twin sister Sabine were born on February 4,

1906. His father, Karl Bonhoeffer, was from a distinguished German family

as was his mother, Paula von Hase. The Bonhoeffers had five children, three boys and two girls, before Dietrich and his sister were born. One daughter was born after Dietrich and Sabine. Bonhoeffer’s father was the leading psychiatrist in Germany, holding a chair at the University of Berlin. He was not openly hostile to Christianity; he allowed his wife to use familiar Christian celebrations as family events. In Bonhoeffer’s family Christianity simply seems to have been part of the furniture upper-class Germans assumed came with their

privileges.

Bonhoeffer’s bearing and personality were undoubtedly shaped by his class. He took full advantage of the cultural and academic resources available to him. He became a talented pianist, and music was a well-spring from which he drew support in the darkest times of his life. That he existed in such a culturally rich family is one reason no one could understand his quite early decision to be a theologian. There had been theologians on both sides of his family, but given the opportunities before him it was not clear why of all the paths he might have taken he decided to be a theologian.

Yet at seventeen Bonhoeffer began his theological studies at Tübingen.

Tübingen was but preparation for his coming back to Berlin to study with the great Protestant liberals — Adolf von Harnack, R. Seeberg, and Karl Holl. Soon recognized as someone with extraordinary intellectual power, he completed his first dissertation under Seeberg’s direction, Sanctorum Communio in 1927. In spite of being at the center of Protestant liberalism, Bonhoeffer had come under the influence of Karl Barth. In Sanctorum Communio, Bonhoeffer displayed the creative synthesis that would mark all his subsequent work — i.e., the firm conviction that Christian theology must insist that “only the concept of revelation can lead to the Christian concept of the church,” coupled with the Lutheran stress on the absolute necessity that the same church known by revelation is also the concrete historical community that in spite of all its imperfections and modest appearances “is the body of Christ, Christ’s presence on earth.”[16]

Bonhoeffer was now on the path to becoming the paradigmatic German

academic theologian. However, for some reason he felt drawn to the ministry and took the examinations necessary to be ordained and appointed to a church. His family continued to assume Bonhoeffer would ultimately become an academic, but he thought his problem “was not how to enter the academic world, it was how to escape it.”[17]Yet he returned to Berlin, finishing his second dissertation, Act and Being, in 1930. In it he develops the Barthian insistence that God’s being is act, but he worries that though Barth readily uses “temporal categories (instant, not beforehand, afterward, etc.), his concept of act still should not be regarded as temporal.”[18]

Before assuming the position of lecturer at the University of Berlin, Bonhoeffer spent a year at Union Seminary in New York. He was not the least attracted to American theology, finding it superficial, but he was drawn deeply to the life of the African-American church. Almost every Sunday Bonhoeffer accompanied his African-American friend, Frank Fisher, to the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem.[19] Though Bonhoeffer’s characterization of the American church as “Protestantism without Reformation” is often quoted, more important for our understanding Bonhoeffer is his observation that the fundamental characteristic of American thought is that “[Americans] do not see the radical claim of truth on the shaping of their lives. Community is therefore founded less on truth than on the spirit of ‘fairness’.”[20] According to Bonhoeffer the result is “a certain levelling” in intellectual demands and accomplishments.

That truth mattered so deeply for Bonhoeffer may account for an extraordinary letter he wrote to a friend in 1936. The letter begins, “Then

something happened.” He does not say what happened but he does say it

transformed his life. Before “something happened,” he confesses he plunged into work in a very unchristian way, but then for the first time “I discovered the Bible . . . I had often preached, I had seen a great deal of the church, spoken and preached about it — but I had not yet become a Christian.”[21] Bonhoeffer continues, confessing he had turned the doctrine of Jesus Christ into something of a personal advantage for himself, but the Bible, and in particular the Sermon on the Mount, freed him from his self-preoccupation. It became clear that “the life of a servant of Jesus Christ must belong to the church, and step by step it became clearer to me how far that must go. Then came the crisis of 1933. This strengthened me in it. The revival of the church and of the ministry became my supreme concern.”[22]

This letter is remarkable not only because of what it tells us about Bonhoeffer, but because it indicates this change is also linked with his becoming a pacifist. “I suddenly saw the Christian pacifism that I had recently passionately opposed to be self-evident.”[23]No doubt coming into contact with Jean Lasserre at Union accounts for Bonhoeffer at least becoming sympathetic to pacifism, but equally important was Bonhoeffer’s passion for the truth. In an address to the Youth Peace Conference in Czechoslovakia in 1932, he says,

There can only be a community of peace when it does not rest on lies and injustice. There is a community of peace for Christians only because one will forgive the other for his sins. The forgiveness of sins still remains the sole ground of all peace, even where the order of external peace remains preserved in truth and justice. It is therefore also the ultimate ground on which all ecumenical work rests, precisely where the cleavage appears hopeless.[24]

Bonhoeffer’s life becomes an unfolding of his complete commitment to

the church. Until he joined the Abwehr, his opposition to the Nazis would be fought through the church in and, perhaps as important, outside Germany. In 1933 he was appointed as pastor to the German Church in London in hopes that such an appointment would allow him to make contacts in order to help the world understand the danger the Nazis represented. That danger he took to be nothing less than the “brutal attempt to make history without God and to found it on the strength of man alone.”[25] While in England Bonhoeffer developed a close and lasting friendship with George Bell, Bishop of Chichester, who worked tirelessly on Bonhoeffer’s behalf.

Before leaving Germany, Bonhoeffer with Martin Niemöller had drafted

the Bethel Confession for the Pastors’ Emergency League, which in the

strongest language possible challenged the anti-semitism of the German Church. The Bethel Confession and the Barmen Declaration became the crucial documents that gave Bonhoeffer hope that the church of Jesus Christ not only existed but was sufficient to provide resistance to the Nazis. He could, therefore, declare in 1936 that “the government of the national church has cut itself off from the Christian church. The Confessing Church is the true church of Jesus Christ in Germany.”[26] He was unafraid to draw the implication — “The question of church membership is the question of salvation. The boundaries of the church are the boundaries of salvation. Whoever knowingly cuts himself off from the Confessing Church in Germany cuts himself off from salvation.”[27]

Bonhoeffer returned to Germany in 1935 in answer to a call from the

Confessing Church to direct a preacher’s seminary at Finkenwalde. His passion for Christian community seems to have found its most intense expression there. During his time there he not only finished Discipleship but also his extraordinary account of Christian community, Life Together.[28]

At Finkenwalde Bonhoeffer not only encouraged seminarians to confess

their sins to another member of the community, but he established with a core group the “House of Brethren” committed to leading “a communal life in daily and strict obedience to the will of Christ Jesus, in the exercise of the humblest and highest service one Christian can perform for another.” Its members “must learn to recognize the strength and liberation to be found in service to one another and communal life in a Christian community. . . . They have to learn to serve the truth alone in the study of the Bible and its interpretation in their sermons and teaching.”[29]

During his time at Finkenwalde Bonhoeffer continued to be engaged in

the ecumenical movement and the work of the Confessing Church.

Developments in the latter could not help but be a continuing disappointment to him. No doubt equally troubling was the conscription and death of many of the students he taught at Finkenwalde. Finally in 1940 the Gestapo closed the seminary, which meant Bonhoeffer was without an ecclesial appointment. He was now vulnerable to conscription. Because of his international connections, Von Dohnanyi justified Bonhoeffer’s appointment to the Abwehr on grounds that through his ecumenical connections he could discover valuable information for the Reich. In effect Bonhoeffer became a double agent, often making trips to Switzerland and Sweden to meet Bell and other ecumenical representatives in the hope that Bell could convince the Allies to state their war aims in a manner that would not make it more difficult for those committed to Hitler’s overthrow.

Without a church connection Bonhoeffer turned again to his passion for theology, beginning work on what we now know as his Ethics. Much of it

was written at the Benedictine monastery at Ettal which served as his retreat from the world. But Bonhoeffer knew no retreat was possible, and he was finally arrested for “subversion of the armed forces” on April 5, 1943. Imprisoned in Tegel prison, he was under interrogation in preparation for being tried. There he wrote most of the material for Letters and Papers from Prison. On July 20, 1944, von Stauffenberg’s attempt on Hitler’s life failed with the subsequent discovery of Canaris’s files in the Zossen bunker. Those files clearly implicated Bonhoeffer and von Dohnanyi in the conspiracy. Bonhoeffer was moved to Buchenwald and finally to Flossenbürg, where he was hanged on April 9. His fellow prisoners and guards testify that throughout his imprisonment he not only functioned as their pastor but died as he had lived.

Bonhoeffer’s life that was at once theological and political. It was so,

however, not because he died at the hands of the Nazis. His life and work

would have been political if the Nazis had never existed; for he saw that the failure of the church when confronted with Hitler began long before the Nazi challenge. Hitler forced a church long accustomed to privileges dependent on its invisibility to become visible. The church in Germany, however, had simply lost the resources to reclaim its space in the world. How that space can be reclaimed — not only in the face of the Nazis but when time seems “normal” — is the heart of Bonhoeffer’s theological politics.

Bonhoeffer’s Recovery of the Church’s Political Significance

In an essay entitled “The Constantinian Sources of Western Social Ethics,”

John Howard Yoder makes the striking observation that after the Constantinian shift the meaning of the word “Christian” changes. Prior to Constantine it took exceptional conviction to be a Christian. After Constantine it takes exceptional courage not to be counted as a Christian. This development, according to Yoder, called forth a new doctrinal development, “namely the doctrine of the invisibility of the church.” Before Constantine, one knew as a fact of everyday experience that there was a church, but one had to have faith that God was governing history. After Constantine, people assumed as a fact God was governing history through the emperor, but one had to take it on faith that within the nominally Christian mass there was a community of true believers. No longer could being a Christian be identified with church membership, since many “Christians” in the church had not chosen to follow Christ. Now to be a Christian is transmuted to “inwardness.”[30]

Bonhoeffer is obviously a Lutheran and Lutherans are seldom confused

with Anabaptists, but his account of the challenge facing the church closely parallels Yoder’s account.[31] For example, in notes for a lecture at Finkenwalde, Bonhoeffer observes that the consequence of Luther’s doctrine of grace is that the church should live in the world and, according to Romans l3, in its ordinances. “Thus in his own way Luther confirms Constantine’s covenant with the church. As a result, a minimal ethic prevailed. Luther of course wanted a complete ethic for everyone, not only for monastic orders. Thus the existence of the Christian became the existence of the citizen. The nature of the church vanished into the invisible realm. But in this way the New Testament message was fundamentally misunderstood, inner-worldliness became a principle.”[32]

Faced with this result Bonhoeffer argues that the church must define its

limits by severing heresy from its body. “It has to make itself distinct and to be a community which hears the Apocalypse. It has to testify to its alien nature and to resist the false principle of inner-worldliness. Friendship between the church and the world is not normal, but abnormal. The community must suffer like Christ, without wonderment. The cross stands visibly over the community.”[33] It is not hard to see how Bonhoeffer’s stress on the necessity of visibility led him to write a book like Discipleship. Holiness but names God’s way of making his will for his people visible. “To flee into invisibility is to deny the call. Any community of Jesus which wants to be invisible is no longer a community that follows him.”[34]

According to Bonhoeffer sanctification, properly understood, is the church’s politics. For sanctification is only possible within the visible church community. “That is the ‘political’ character of the church community. A merely personal sanctification which seeks to bypass this openly visible separation of the church-community from the world confuses the pious desires of the religious flesh with the sanctification of the church-community, which has been accomplished in Christ’s death and is being actualized by the seal of God. . . . Sanctification through the seal of the Holy Spirit always places the church in the midst of struggle.”[35] Bonhoeffer saw that the holiness of the church is necessary for the redemption of the world.[36]

I am not suggesting that when Bonhoeffer wrote Sanctorum Communio,

he did so with the clarity that can be found in the lectures he gave at Finkenwalde or in his Discipleship. In Sanctorum Communio his concerns may be described as more strictly theological, but even that early the “strictly theological” was against the background of Protestant liberal mistakes, and in particular Ernst Troeltsch, that made inevitable his unease with the stance of the German churches toward the world. According to Bonhoeffer, “The church is God’s new will and purpose for humanity. God’s will is always directed toward the concrete, historical human being. But this means that it begins to be implemented in history. God’s will must become visible and comprehensible at some point in history.”[37]

Throughout his work Bonhoeffer relentlessly explores and searches for

what it means for the church to faithfully manifest God’s visibility. For example,in his Ethics, he notes that the church occupies a space in the world through her public worship, her parish life, and her organization. That the church takes up space is but a correlative to the proposition that God in Jesus Christ occupies space in the world. “And so, too, the Church of Jesus Christ is the place, in other words the space in the world, at which the reign of Jesus Christ over the whole world is evidenced and proclaimed.”[38] Bonhoeffer’s ecclesiology is the expression of his Christology in which the reality of Christ determines all that is.

For Bonhoeffer it is in Jesus Christ that the whole of reality is taken up,

that reality has an origin and an end. For that reason it is only in Him, and with Him as the point of departure, that there can be an action which is in accordance with reality. The origin of action which accords with reality is not the pseudo- Lutheran Christ who exists solely for the purpose of sanctioning the facts as they are, nor the Christ of radical enthusiasm whose function is to bless every revolution, but it is the incarnate God Jesus who has accepted man and who has loved, condemned, and reconciled man and with him the world.[39]

As Christ was in the world, so the Church is in the world. These are not

pious sentiments, but reality making claims that challenge the way things are. They are the very heart of Bonhoeffer’s theological politics, a politics that requires the church to be the church in order that the world can be the world. Bonhoeffer’s call for the world to be the world is the outworking of his Christology and ecclesiology. For the church to let the world be the world means the church refuses to live by privileges granted on the world’s terms. “Real secularity consists in the church’s being able to renounce all privileges and all its property but never Christ’s Word and the forgiveness of sins. With Christ and the forgiveness of sins to fall back on, the church is free to give up everything else.”[40] Such freedom, moreover, is the necessary condition for the church to be the zone of truth in a world of mendacity.[41]

Sanctorum Communio was Bonhoeffer’s attempt to develop a “specifically Christian sociology” as an alternative to Troeltsch.[42] Bonhoeffer argues that the very categories — church/sect/mysticism, Gemeinschaft/ Gesellschaft — must be rejected if the visibility of the church is to be reclaimed. Troeltsch confuses questions of origins with essences, with the result that the gospel is subjected to the world. The very choice between voluntary association and compulsory organization is rendered unacceptable by the “Protestant understanding of the Spirit and the church-community, in the former because it does not take the reality of the Spirit into account at all, and in the latter in that it severs the essential relation between Spirit and church-community, thereby completely losing any sociological interest.”[43]

From Bonhoeffer’s perspective Troeltsch is just one of the most powerful

representatives of the Protestant liberal presumption that the gospel is purely religious, encompassing the outlook of the individual, but indifferent and unconcerned with worldly institutions.[44] The sociology of Protestant liberalism, therefore, is simply the other side of liberal separation of Jesus from the Christ. Protestant liberalism continues the docetic Christological heresy that results in an equally pernicious docetic ecclesiology.[45] Protestant liberalism is the theological expression of the sociology of the invisible church that “conceded to the world the right to determine Christ’s place in the world; in the conflict between the church and the world it accepted the comparatively easy terms of peace that the world dictated. Its strength was that it did not try to put the clock back, and that it genuinely accepted the battle (Troeltsch), even though this ended with its defeat.”[46]

Bonhoeffer’s work was to provide a complete alternative to the liberal

Protestant attempt to make peace with the world. In a lecture at the beginning of his Finkenwalde period concerning the interpretation of scripture, Bonhoeffer asserts that the intention “should be not to justify Christianity in this present age, but to justify the present age before the Christian message.”[47] Bonhoeffer’s attack in Letters and Papers from Prison on the liberal Protestant apologetics that tries to secure “faith” on the edges of life and the despair such edges allegedly create is a continuation of his attack on Protestant pietism and his refusal to let the proclamation of the Gospel be marginalized. For the same reasons he had little regard for existentialist philosophers or psychotherapists, whom he regarded as exponents of a secularized methodism.[48]

Unfortunately, Bonhoeffer’s suggestion about Barth’s “positivism of

revelation” and the correlative need for a nonreligious interpretation of

theological concepts has led some to think Bonhoeffer wanted Christians to become “secular.”[49] The exact opposite is the case. Bonhoeffer insists that if reality is redeemed by Christ, Christians must claim the center, refusing to use the “world’s” weakness to make the Gospel intelligible. He refuses all strategies that try “to make room for God on the borders” thinking it better to leave certain problems unsolved. The Gospel is not an answer to questions produced Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Political Theology 29

by human anxiety but a proclamation of a “fact.” Thus Bonhoeffer’s wonderful remark: “Belief in the Resurrection is not the solution to the problem of death. God’s ‘beyond’ is not the beyond of our cognitive faculties. The transcendence of epistemological theory has nothing to do with the transcendence of God. God is beyond in the midst of life. The church stands, not at the boundaries where human powers give out, but in the middle of the village.”[50]

Bonhoeffer’s call for a Christian worldliness, moreover, is not his turning

away from the kind of community discipline he so eloquently defended in

Discipleship and Life Together. In his confession in Letters and Papers from Prison that at one time he mistakenly assumed he could acquire faith by living a holy life, he is not rejecting the form of life lived at Finkenwalde. When he says he now sees some of the dangers of Discipleship, though he still stands by that book, he is continuing to reject the false dualism inherited from Troeltsch. Rather, he is making the Christological point that the incarnation, the crucifixion, and the resurrection must be held in unity to rightly understand the church’s relationship to the world. An emphasis on incarnation too often leads to compromise; an ethic based on cross and resurrection too often leads to radicalism and enthusiasm.[51] The church names that community that lives in radical hope in a world without hope. To so live means the church cannot help but be different from the world. Such a difference is not an end in itself but “automatically follow[s] from an authentic proclamation of the gospel.”[52]

This I believe to be Bonhoeffer’s theological politics. He sought to

recover the visibility of the church because “it is essential to the revelation of God in Jesus Christ that it occupies space within the world.”[53]Put positively, in Jesus Christ God has occupied space in the world and continues to do so through the work of the Holy Spirit’s calling the church to faithfulness. These were the convictions that Bonhoeffer brought to his war with the Nazis and that made him the most insightful and powerful force shaping the church’s witness against Hitler. Yet in a sense Hitler was exactly the kind of enemy that makes Bonhoeffer’s (and Barth’s) theological politics so compelling. The question remains, however, whether Bonhoeffer (or Barth) provides an adequate account of how the church must negotiate a world “after Christendom.” To consider that question, I must explore what might be called Bonhoeffer’s “political ethics,” which are expressed primarily by his critique and attempt to find an alternative to the traditional Lutheran doctrine of the two kingdoms.

Bonhoeffer’s Search for a Political Ethic

At a conference sponsored by the Church Federation Office in 1932, Bonhoeffer (even though he was the youngest speaker at the conference) vigorously attacked the idea of the “orders of creation” introduced by traditional Lutherans. That he would reject the two-kingdom tradition was inevitable, given the direction he had begun in Sanctorum Communio and Act and Being. Creation simply cannot be self-validating because Christians have no knowledge of creation separate from redemption. “The creation is a picture of the power and faithfulness of God, demonstrated to us in God’s revelation in Jesus Christ. We worship the creator, revealed to us as redeemer.”[54] Whatever Christians have to say about worldly order, it will have to be said on the presumption that Christ is the reality of all that is.

Bonhoeffer soon returned to the issue of the “orders of creation” in a

address to the Youth Peace Conference in Czechoslovakia in July 1932. Again he attacks those who believe that we must accept certain orders as given in creation. Such a view entails the presumption that because the nations have been created differently each one is obliged to preserve and develop its own characteristics. He notes this understanding of the nation is particularly dangerous because “just about everything can be defended by it.” Not only is the fallenness of such order ignored, but those that use the orders of creation to justify their commitment to Germany fail to see that “the so-called orders of creation are no longer per se revelations of the divine commandment, they are concealed and invisible. Thus the concept of orders of creation must be rejected as a basis for the knowledge of the commandment of God.”[55]

However, if the orders of creation are rejected, then Bonhoeffer must

provide some account of how Christians understand the commandment of

God for their lives. In Creation and Fall he notes that the Creator does not

turn from the fallen world but rather deals with humankind in a distinctive

way: “He made them cloaks.” Accordingly, the created world becomes the

preserved world by which God restrains our distorted passions. Rather than

speaking of the orders of creation, Bonhoeffer begins to describe God’s care of our lives as the orders of preservation.[56] The orders of preservation are not self-validating, but “obtain their value wholly from outside themselves, from Christ, from the new creation.”[57] Any order of the world can, therefore, be dissolved if it prevents our hearing the commandment of Christ.

What difference for concrete ethical reflection flows from changing the

name from “creation” to “preservation”? Bonhoeffer is obviously struggling

to challenge how the Lutheran “two order” account both fails to be Christological and serves as a legitimation of the status quo. In Christ the Center, lectures in Christology he delivered at Berlin in 1933, Bonhoeffer spelled out some implications of his Christological display of the orders of preservation. For example, he observed that since Christ is present in the church after the cross and resurrection, the church must be understood as the center of history. In fact, the state has only existed in its proper from only so long as there has been a church, because the state has its proper origin with the cross. Yet the history of which the church is the center is a history made by the state. Accordingly, the visibility of the church does not require that the church must be acknowledged by the state by being made a state church, but rather the church is the “hidden meaning and promise of the state.”[58]

But if the church is the state’s “hidden meaning,” how can the state

know that the church is so, if the church is not visible to the state? How is this “hiddenness” of the church for the state congruent with Bonhoeffer’s insistence on the church’s visibility? Bonhoeffer wants the boundaries of the church to challenge or at least limit the boundaries of the state, but he finds it hard to break Lutheran habits that determine what the proper role of the state is in principle. Thus he will say that the kingdom of God takes form in the state insofar as the state holds itself responsible for stopping the world from flying to pieces through the exercise of its authority; or, that the power of loneliness in the church is destroyed in the confession-occurrence, but “in the state it is restrained through the preservation of community order.”[59] Understandably, Bonhoeffer does not realize that he is not obliged to provide an account in

principle of what the state is or should be.

In his Ethics Bonhoeffer seems to have abandoned the language of

“orders of preservation” and instead uses the language of “mandates.”[60] For Bonhoeffer, the Scriptures name four mandates — labor, marriage, government, and the church.[61] The mandates receive their intelligibility only as they are created in and directed towards Christ. Accordingly, the authorization to speak on behalf of the Church, the family, labor, and government is conferred from above and then “only so long as they do not encroach upon each other’s domains and only so long as they give effect to God’s commandment in conjunction and collaboration with one another and each in its own way.”[62] Bonhoeffer does not develop how we would know when one domain has encroached on the other or what conjunction or collaboration might look like.[63]

It is clear what Bonhoeffer is against, but it is not yet clear what he is

for. He is against the distinction between “person” and “office” he attributes to the Reformation. He notes this distinction is crucial for justifying the Reformation position on war and on the public use of legal means to repel evil. “But this distinction between private person and bearer of an office as normative for my behavior is foreign to Jesus,” Bonhoeffer argues. “He does not say a word about it. He addresses his disciples as people who have left everything behind to follow him. ‘Private’ and ‘official’ spheres are all completely subject to Jesus’ command. The word of Jesus claimed them undividedly.”[64] Yet Bonhoeffer’s account of the mandates can invite a distinction between the private and the public which results in Christian obedience becoming invisible.

Bonhoeffer’s attempt to rethink the Lutheran two-kingdom theology in

the light of his Christological recovery of the significance of the visible church failed, I think, to escape from the limits of habits that have long shaped Lutheran thinking on these matters. However, there is another side to Bonhoeffer’s political ethics that is seldom noticed or commented on. Bethge notes that though Bonhoeffer was shaped by the liberal theological and political tradition, by 1933 he was growing antiliberal not only in his theology but in his politics. Increasingly he thought liberalism — because of either a superciliousness or a weak laissez-faire attitude — was leaving decisions to the tyrant.[65]

Nowhere are Bonhoeffer’s judgments about political liberalism more clearly stated than in a response he wrote in 194l to William Paton’s The Church and the New World Order, a book that explored the church’s responsibility for social reconstruction after the war. Bonhoeffer begins by observing that the upheavals of the war have made European Christians acutely

conscious that the future is in God’s hands and no human planning can make men the masters of their fate. Consequently, churches on the continent have an apocalyptic stance that can lead to other-worldliness but may also have the more salutary effect of making Christians recognize that the life of the church has its own God-given laws which differ from those governing the life of the world. Accordingly, the church cannot and should not develop detailed plans for reconstruction after the war, but rather it must remind the nations of the abiding commandments and realities that must be taken seriously if the new order is to be a true order.[66]

In particular, Bonhoeffer stresses that in a number of European countries

an attempt to return to full-fledged democracy and parliamentarianism would create even more disorder than obtained prior to the era of authoritarianism. Democracy requires a soil prepared by a long spiritual tradition and most of the nations of Europe, except for some of the smaller ones, do not have the resources for sustaining democracy. This does not mean that the only alternative is state absolutism, but rather that what should be sought is for each state to be limited by the law. This will require a different politics from the politics of liberalism.

In his Ethics Bonhoeffer starkly states (he has in mind the French Revolution) that “the demand for absolute liberty brings men to the depths of slavery.”[67] In his response to Paton, he observes that the Anglo-Saxon word that names the struggle against the omnipotence of the state is “freedom,” and the demand for freedom is expressed in the language of “rights and liberties.”[68] But “freedom is a too negative word to be used in a situation where all order has been destroyed. And liberties are not enough when men seek first of all for some minimum security. These words remind us much of the old liberalism which because of its failures is itself largely responsible for the development of State absolutism.”[69]

Bonhoeffer takes up this history again in his Ethics, suggesting that these developments cannot help but lead to godlessness and the subsequent

deification of man, which is the proclamation of nihilism. This “hopeless

godlessness” is seldom identified by hostility to the church but rather comes too often in Christian clothing. Such “godlessness” is particularly present, he finds, in the American churches which seek to faithfully build the world with Christian principles and ends with the total capitulation of the church to the world. Such societies and churches have no confidence in truth, with the result that the place of truth is usurped by sophistic propaganda.[70]

The only hope, if Europe is to avoid a plunge into the void after the

war, is in the miracle of a new awakening of faith and the institution of God’s governance of the world that sets limits to evil. The latter alternative, what Bonhoeffer calls “the restrainer,” is the power of the state to establish and maintain order.[71] In his reply to Paton he suggests that such an order limited by law and responsibility, which recognizes commandments that transcend the state, has more “spiritual substance and solidity than the emphasis on the rights of man.”[72] Such an order is entirely different from the order of the church, but they are in close alliance. The church, therefore, cannot fail its responsibility to sustain the restraining work of the state.

Yet the church must never forget that her primary task is to preach the

risen Jesus Christ, because in so doing she “strikes a mortal blow at the spirit of destruction. The ‘restrainer,’ the force of order, sees in the church an ally, and, whatever other elements of order may remain, will seek a place at her side. Justice, truth, science, art, culture, humanity, liberty, patriotism, all at last, after long straying from the path, are once more finding their way back to their fountain-head. The more central the message of the church, the greater now will be her effectiveness.”[73]

Above I suggested that Bonhoeffer’s attempt to reclaim the visibility of

the church at least put him in the vicinity of trying to imagine a non-Constantinian church. Yet in his Ethics he displays habits of mind that seem committed to what we can only call a “Christian civilization,” though Larry Rasmussen suggests that Bonhoeffer in the last stages of Letters and Papers from Prison began to move away from any Christendom notions.[74]Rasmussen directs our attention to the “Outline for a Book” Bonhoeffer wrote toward the end of his life. Rather than finishing the Ethics, which he expressed regret for not having done, if Bonhoeffer had lived, I believe, as does Rasmussen, he would have first written the book envisaged in his “Outline.” The book hinted at there would have allowed Bonhoeffer to extend his reflections about the limits of liberal politics and in what manner the church might provide an appropriate alternative.

In his “Outline” Bonhoeffer begins with “a stocktaking of Christianity.”