Title of Contents

Foreword

Articles

Book Reviews | Full Book Review Section (PDF)

Foreword

The centerpiece of this omnibus issue is the 2003 Benjamin Eby Lecture, presented at Conrad Grebel University College last November by John E. Toews, the former president of the College. The equal product of many years experience and much reflection, “Rethinking the Meaning of Ordination: Toward a Biblical Theology of Leadership Affirmation,” is bound to provoke discussion and debate. In fact, it already has: We are pleased to present here, in tandem with that Lecture, an invited essay by Loren Johns, entitled “Ordination and Pastoral Leadership: A Response to John E. Toews.”

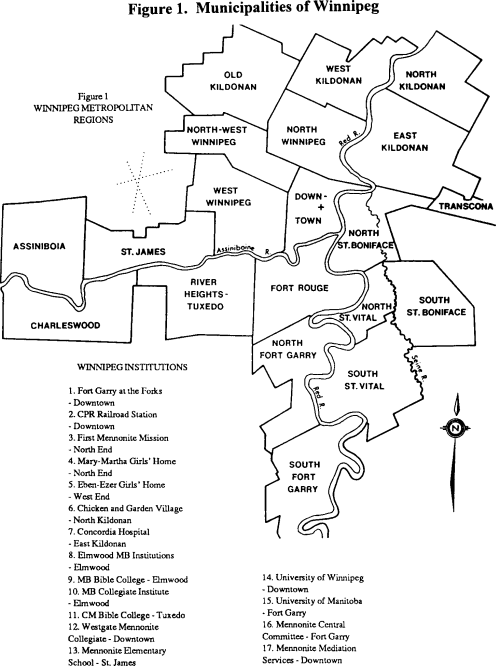

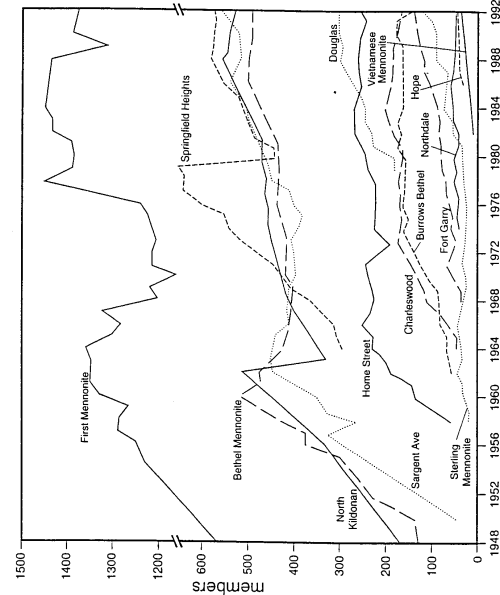

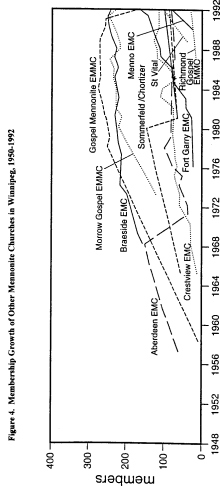

Two substantial papers complete the main body of this issue. Longtime University of Manitoba sociologist Leo Driedger traces “external” factors, as distinct from “internal” factors identified by church growth researchers such as Lyle Schaller and Christian Schwarz, that account for the development of Mennonite churches in Winnipeg. Tripp York, a doctoral student at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, seeks to “uncover what it means to be a church predicated on the memory of its martyrs” as he mines Balthasar Hubmaier’s teaching for insight into the “formative capabilities” of the Lord’s Supper today.

With this issue we revert to publishing more book reviews than has lately been our norm. Readers will find an array of reviews examining recent releases in theology, church history, biography, Biblical studies and several other fields. We’re still trying to catch up, and we appreciate the patience of reviewers whose diligent efforts of some months ago are only now getting into print.

Amazingly attentive readers will notice that this issue departs from the previously announced schedule. The Eby Lecture was originally slated for our Spring 2004 number, but that issue will instead be devoted to the work of writer Rudy Wiebe. While we make no firm promises – we don’t do that anymore – we do intend at this point to follow the following schedule. The Fall 2004 issue will deal with the theology of John Milbank; the Winter 2005 issue will feature papers from the 2003 Mennonite World Conference plus the 2004 Bechtel Lecture by MWC president Nancy Heisey; and the Spring 2005 issue will offer proceedings of the latest Women Doing Theology conference.

We invite readers to stay with us for these and other forthcoming issues as we continue to provide a vibrant forum for thoughtful, sustained discussion of spirituality, ethics, theology, and culture from a broadly-based Mennonite perspective.

C. Arnold Snyder, Academic Editor

Stephen A. Jones, Managing Editor

The Conrad Grebel Review 22 no. 1 (Winter 2004)

The 2003 Benjamin Eby Lecture

Introduction

I have been interested in and involved in church leadership my entire adult

life. I come from a family with a long history of influential and significant

church leaders. I have taught in three different Mennonite colleges where

we worked hard to nurture young people into church ministry. I worked for

nearly twenty years in a seminary setting where the clear mandate was the training of ministers for the church. I personally have been involved in church leadership roles – local, national, bi-national, institutional. I believe in the importance of clearly defined and strong church leadership. Yet throughout this forty-five year history I have struggled with the concept of ordination as the means of affirming and legitimating church leaders. The theology and the practice of ordination seems out of sync with an Anabaptist-Mennonite understanding of the church and church ministry.

The ordination of ministers is a long-time practice in the Christian church whereby the church “sets aside” selected individuals and both recognizes them as ministers and empowers them to be leaders. The act of ordination in many churches is viewed as a sacramental event – it confers lifetime grace, authority, and status. While many Protestant churches, including Mennonite churches, have tried to de-sacramentalize ordination, the long-time underlying assumption and reality is sacramental. It continues to confer lifetime status, it is understood as “a life-shaping and identity-giving moment” (Mennonite Polity, 30), it places one into a special “office of ministry,” and it confers special privileges and status.

The tradition and practice of ordination is increasingly being questioned in the ecumenical church. Thomas Talley, in an assessment of the state of ordination thinking in the Episcopal Church, asserts that “hardly any area of liturgical and sacramental theology and practice is more disputed” (Talley, 4). John Brug says the same is true in the Lutheran tradition (Brug, 263). The questions are multiple: What is ordination? What does it mean? Who should be ordained? Who ordains? Is laying on of hands an essential part of ordination? Is there a biblical basis for ordination? What does ordination give?

The Mennonite Church traditions (MC and GC) reflect a long practice

of ordination for the threefold offices of the church – bishop, preacher, deacon. While the polity of the traditions has changed significantly over the years, the practice of ordination has remained constant (see Mennonite Polity, 32-72). The “recovery of the Anabaptist Vision” movement, especially the Concern Group and the Dean’s Seminar at Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminaries, did raise questions about ordination. John H. Yoder, one of the key theologians of both groups, stated that “there is . . . no ground for seeing in the New Testament usage a clear conception of ordination as applying to some Christians

and not to others” (Yoder, 1969, 61). Selected individuals in the 1960s and ’70s refused ordination because of these questions, but the larger church continued the practice. More recently it has even strengthened the practice of ordination by linking it to the “office of ministry” and by the use of oil in the service of ordination in some parts of the church. The introduction of anointing with oil, or Chrismation, is an OT tradition associated with the coronation of kings and the consecration of priests, and was deemed to impart a holy character to the anointed by removing them from the realm of the profane. The early church did not practice anointing with oil because of its rejection of priestly conceptions of church leadership. The practice was not introduced into the Christian tradition until the Middle Ages (see Ferguson, 1974, 282). Its recent use in the Mennonite Church is puzzling.

The recent emphasis on ordination and the increased “sacralization”

of the practice did not involve any careful review of the biblical texts. The

Mennonite Polity document quotes Erland Waltner to say that the practice

of ordination has “a clear biblical basis” (35), but does not examine the relevant texts. John Esau, one of the key leaders in the drafting of A Mennonite Polity for Ministerial Leadership, informs me that the committees formulating the document thought the biblical texts were too early to be helpful (July 7, 2003, email).

The most recent Mennonite Church Ministers Manual acknowledges

the lack of New Testament teaching, but then makes a most interesting move. “The roots of ordination,” it asserts, “go back to the Hebrew Bible and the instructions given to Moses to consecrate Aaron and his sons as priests for the congregation of God’s people (Ex. 29 and Lev. 8-10)” [see Ministers Manual, 1998, 144]. That is a hermeneutical move not made in the history of the church until the sacradotalization of church ministers as priests in the Constantinian church.

Mennonite Brethren, the second largest Mennonite body in North

America, began to “ordain” ministers in the late 1860s with a great deal of

reluctance, due to questions about the biblical foundation for ordination and concerns about the hierarchical values and structures implicit in the practice of ordination (see Heidebrecht, 62ff.). This early ambivalence has continued to characterize Mennonite Brethren thinking. F. C. Peters initiated the most recent round of study and discussion in his 1969 keynote address to the General Conference by asking, “If in theory we do not have a sacramental view of ordination are we in danger of operating functionally on such a premise?” (Peters, 4). Peters’s question resulted in four study conference papers (Orlando Wiebe, 1970; John Regehr, 1976; Victor Adrian, 1980; Tim Geddert, 1994), one thesis (Harry Heidebrecht, 1971) and one General Conference resolution (1981). All of the studies and the resolution struggle with the theological problematic of ordination. The 1981 resolution was barely approved before there were renewed calls for a study of the question of ordination. By 1987 the restlessness was so great that the Board of Reference and Counsel publicly announced that it would again study the question (the 1994 Study Conference).

Two issues create uncertainty in studies on ordination: the weak biblical foundations, and the relation of ordination to the gifting of all believers for ministry.

A series of biblical scholars since the 1970s have raised serious questions about the biblical basis for ordination, e.g., Giles, Ferguson, Flemming, Kilmartin, Morris, Peacock, Schweizer, Warkentin, D.F. Wright. Martin Kilmartin asserts that “almost every issue related to the subject remains unresolved” (Kilmartin, 45). David Wright stresses that “uncertainties attend much of the New Testament material supposedly germane to ordination. Only one text, 1 Timothy 4.14, can with firm confidence be regarded as attesting an observance 8 The Conrad Grebel Review recognizable in subsequent church history as ordination to ‘the ministry’” (D.F. Wright, 7). Wright goes on to claim that “a yawning gulf is exposed between the Pastorals and the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus over a century later” (Wright, 7). Dean Flemming states that “there is no evidence that ordination to office was a regular practice in the early church” (Flemming, 244). Kevin Giles adds that “the fog is almost impenetrable” regarding ordination (Giles, 173).

The problem is that the NT outlines a clear theology of church ministry based on charisma, but says little about the affirmation or installation of people for ministry. Christ gives gifts to all believers for the well-being and ministry of the church. Some people are given special gifts to equip and order the many diverse gifts in the church (see Rom. 12; 1 Cor. 12; Eph. 4). But there is very little evidence for rites to commission or affirm these people for ministry. The first evidence for commissioning known as ordination comes from Hippolytus’s Apostolic Tradition in the early third century. There is no unanimity among scholars about the use of anything resembling ordination in the first two centuries of the church. The reason is the scarcity of textual evidence for commissioning services or procedures. Any confidence in the use of commissioning procedures in those centuries is based on the assumption of uniformity with the understanding and practice of the orthodox churches in the third century.

The primary purpose of this lecture is to examine the biblical evidence

claimed in support of ordination to church ministry. It begins with the texts

considered foundational, 1 and 2 Timothy, and then moves to other NT texts that have been viewed as relevant or supportive of ordination. The paper concludes with a brief a proposal for affirming people in the church for ministry.

The Foundation Texts

1 Timothy 4.14 Continuously do not neglect the gift (charisma) in you which was given you by means of prophecy (dia = ablative of means) in association with the laying on of the hands (meta = genitive of attendant circumstances) of the elder group.

This is the anchor text for the Christian theology and practice of ordination for ministry. Most commentators see here a clear teaching and practice of ordination. Donald Guthrie links the gift with the event of ordination to ministry (Guthrie, 98). Martin Dibelius and Hans Conzelmann see the event as a sacramental act in which the grace of office is transferred. The hands serve as a means of transferring power (Dibelius and Conzelmann, 70). Raymond Collins asserts that “this is a ritualized gesture signifying a transfer of power. . . .” (Collins, 130; see also Bassler, 87; Knight, 209).

A closer look at the text raises serious questions about this interpretation. The purpose of 1 Timothy is to instruct Timothy on dealing with false teachers within the church who are leading astray some Christians in different house churches. The larger text unit for this particular text is 4.6-16. Timothy’s personal responsibility is the agenda. The unit consists of two paragraphs, vv. 6-10, 11-16. The first paragraph offers instructions vis-à-vis the false teachers. In contrast to these teachers, Timothy must guard his own life and teaching. The second paragraph instructs him to function as a model (vv. 15-16) in godly living despite his youth (v. 12), in the public reading and teaching of scripture (v. 13), in the nurture of the spiritual gift (charisma) given him (v. 14). Timothy has received a charisma, a spiritual gift. A charisma denotes a special endowment of the Spirit that enables a believer to carry out some function or ministry in the community. What the precise gift is we are not told. All we know is that Timothy is to nurture the gift he received.

The gift is associated with prophecy. In fact, it was given through a

prophecy that was associated with the laying on of the hands of the leadership body of the church (presbyteron is singular). That is, Timothy’s gift involved a charismatic communication and community affirmation; the Spirit communicated something and the church responded affirmatively. A prophecy involving Timothy has already been referred to in 1.18, “prophecies leading to you.” That prophecy seems to involve “Paul’s” finding Timothy, and so is probably not the same prophecy as in this text (“Paul” is in quotation marks to indicate uncertainty and debate about the authorship of the Pastoral Letters).

Not only does the text not define the nature of the charisma, it does not define the relationship of the charisma to the prophecy and the laying on of hands. Further, the whole event only confers a gift; it does not confer authority or office. The text says nothing more than that Timothy received an undefined charisma that is to be nurtured as a model for other believers. The text does not say this charisma is for office or of office, nor that the charisma is the ground for the authority of Timothy. Furthermore, charisma and prophecy are features associated with charismatic leadership, not with leadership of office. Timothy is never called an elder, so ordination to the presbytery is hardly the suggestion here. In fact, he is not even a local church leader or model of a particular office in this letter. He is certainly not “the pastor” of the church, as in so much popular literature. Rather, he is “Paul’s” missionary assistant who visits the churches as “Paul’s” personal representative with the intent of returning to “Paul” soon. He simply represents “Paul” to the churches in the apostle’s absence.

1 Tim. 4.14 does not indicate the nature of the gift Timothy received or what the referent of laying on of hands is. It could be Timothy’s conversion/baptism as much as his gifting for ministry. I. Howard Marshall correctly argues that “it is important not to interpret the passage anachronistically in the light of later concepts of ordination” (Marshall, 569).

1 Timothy 5.22 And do not be hastily laying (present imperative) hands on, nor participating in another’s sins; continuously keep yourself pure (present imperative).

The context and text have puzzled scholars for centuries. What is the relation of vv. 21-25 to vv. 17-20? Do we have one text unit addressing presbyters or two text units addressing presbyters and sinners as two different groups? How does the personal admonition to Timothy in v. 23 fit into the logic of the structure?

Interpreters are divided over the meaning of v. 22. Does it refer to

ordination or to the restoration of a disciplined believer? The issue has to do with the relationship of v. 22 to the preceding. V. 20 indicates that there are elders in the church who are sinning. V. 21 says they must be rebuked publicly. If v. 22 is linked to the preceding, then it outlines some guidelines for the replacement of rebuked elders. V. 22 consists of three imperatives. The first follows from what has just been said in v. 21. Do not be hasty in laying on hands for leadership ministries in the church. Exercise caution in the laying on of hands because of the problem of sin in people’s lives. The problem of covering up the sins of leaders leads to the next imperative, Take no part in the sins of others. The last imperative, Keep yourself pure, suggests that the second one means Do not involve yourself in the kinds of sins that have caused some leaders to be rebuked (so Fee, 1984, 91-2; Guthrie, 107; Kelly, 127; Meier, 234-36).

The alternative interpretation argues that vv. 22 and 23 are not linked to the preceding. Instead, they represent individual and separate items of counsel to Timothy. V. 22 is then interpreted to mean the reconciliation of a disciplined believer, an interpretation that links the concerns of v. 22 with 24. The restoration of penitent sinners was part of early church practice (2 Cor. 2.6-11; Jas. 5.15), and was accompanied in the later church (third century on) by the laying of hands (so Dibelius and Conzelmann, 80; Collins, 149; Hanson, 103; Marshall, 621). Both Tertullian and Nicholas of Lyra understood the text in this way.

What is clear is that the text instructs caution in the laying on of hands because of the problem of human fallenness. V. 25 adds a positive reason for such caution: it takes time to discern the good works of some people. The specific referent of this caution is unknown, but probably has more to do with restoring repentant sinners than with any kind of appointment to church ministry.

2 Timothy 1.6 On account of which I am reminding you to be

rekindling the gift of God which is in you by means (dia = ablative of means) of the laying on of my hands.

The purpose of 2 Timothy is to call Timothy to “Paul’s” side and to appeal to his loyalty. V. 6 is the opening statement of the first appeal, vv. 6-14. It follows the thanksgiving of the letter, vv. 3-5, which concludes with gratitude for the faith Timothy has received from his maternal lineage. The text unit urges Timothy to be steadfast and loyal.

While most interpreters see in v. 6 a reference to Timothy’s ordination, nothing in the text suggests such a referent. The “therefore, I remind you to rekindle the gift of God” must refer to what precedes in the text, that is, to the faith Timothy received and owned personally (“which is in you”). The gift of God is the gift of trusting the gospel. That gift is linked to the Holy Spirit at the beginning and end of the text unit (vv. 7, 14). The Spirit gives power, love, and self-control, and “dwells within you.” What follows only supports this interpretation. The concern is faithfulness to the gospel. The “by means of the laying on of my hands” refers to an initiatory event akin to the incidents in Acts in which the Spirit was received through the laying on of apostolic hands (so Marshall, 698; Wright, 6). The point of v. 6 is an affirmation of initial faith, not an affirmation for church ministry or office.

Summary of Teachings in the Pastoral Letters

The Pastoral Letters, the foundational texts for the church’s doctrine and

practice of ordination, turn out to say little about it. Wright suggests that only one biblical text, 1 Tim. 4.14, resembles the church’s understanding and practice of ordination. This study raises questions if even that text can be claimed for this matter. 1 Tim. 4.14 tells us only that Timothy received a charisma through the laying on of hands. We do not know what the gift was, nor what the relationship between it and prophecy and the laying on of hands might be. If church leadership is involved it is charismatic leadership, not the leadership of office or position. 1 Tim. 5.22 says only that Timothy should be cautious in the practice of laying on hands, whether church leadership or restoration of an excommunicated believer is involved. 2 Tim. 1.6 refers to Timothy’s initiation into the Christian faith, not his affirmation for church leadership.

On close examination the foundation texts prove to be sand, not stone. We therefore would do well to practice the admonition to Timothy to be cautious about using these texts to construct a theology and practice of ordination.

Other Relevant New Testament Texts

A series of other texts in the NT describe the practice of “the laying on of

hands” and have been used to make the case for the practice of ordination.

Acts 6.5-6 describes the selection of seven leaders to assist the apostles by serving tables:

and the word pleased the whole multitude, and they chose . . . and they set them before the apostles, and having prayed they laid the hands on them.

Acts 8.17 pictures an apostolic mission to new converts in Samaria:

Peter and John prayed with them . . . and they laid the hands upon them

and they received the Holy Spirit.

V. 18 adds that “through the laying on of the apostle’s hands” the Spirit was given.”

Acts 9.17 narrates the healing and commissioning of Paul following his encounter with the risen Christ on the road to Damascus: Ananias . . . entered the house, and having laid his hands upon him, said, ‘Brother Saul, the Lord sent me, Jesus who appeared to you in the way by which you came, in order that you may see again and may be filled with the Holy Spirit.’

Acts 13.3 describes the calling of Barnabas and Saul from the churches in Antioch to a special but undefined ministry:

And there were in Antioch in the church prophets and teachers . . . and while they were worshipping the Lord and fasting, the Holy Spirit said, ‘Set apart to me Barnabas and Saul for the purpose of the work to which I have already called them.’ Then having fasted and prayed and having laid hands on them, they loosed them (apoluo).

Acts 19.6 pictures Paul’s mediation of the Spirit to disciples in Ephesus:

And when Paul laid the hands on them the Holy Spirit came upon them,

and they were speaking in tongues and prophesying.

Hebrews 6.2 urges that the elementary doctrines be left behind, one of which is “the laying on of hands.” The context makes it clear that initiation into the Christian faith is described by “the laying on of hands.”

Commentary

There are three types of “laying on of hands” texts in the NT. One type

describes healings. Jesus healed by laying on hands, e.g., Mark 8.25; Matthew 19.13, 15. The same language is used in Acts 19.11 and 28.8, and perhaps also in Acts 20.10 and James 5.14-15. Touch is the primary element in this laying on of hands, as in actions of blessing in the OT. The second type is associated with initiation and incorporation of people into the Christian church. The third type is connected with affirmation for church ministry.

The other relevant texts deal with two of these types. Four of the texts deal with initiation into the Christian faith and church, e.g., Acts 8.17; 9.17; 19.6; Hebrews 6.2. All are linked to prayer and to the coming of the Holy Spirit into the lives of believers. This use of the laying on of hands is without parallel in the OT and in Judaism.

Two of the texts deal with affirmations for church ministries, e.g., Acts 6.6 and 13.3. The narrative of Acts is clearly concerned with affirming people for ministries in the church, but the affirmation takes place in different ways. People are selected by community election in chapter 6, by the calling of fellow leaders in chapter 13, by the appointment of the apostles in 14.23. The selection of leaders in 13.3 and 14.23 involves preparatory prayer and fasting, but not so in 6.6 and 13.3. There is laying on of hands in 6.6 and 13.3, but not in 14.23. There is no suggestion in 6.6 and 13.3 that the laying on of hands involved the imparting of spiritual gifts. Rather, it was an act of recognition of gifts already possessed. The seven were required to be “full of the Spirit” prior to their commissioning (vv. 3, 5). The laying of hands on them is a “lay” commissioning to a particular service. The appointment is not unlike that of the Levites. Like the latter, the seven are dedicated by the entire congregation for acts of service that are subordinate to the apostles, as the Levites were subordinate to the priests. Barnabas and Saul were already among the prophets and teachers of the church before the laying on of hands. They are simply commissioned for a specific “work” (ergon) [so Barrett, 599; Fitzmyer, 351; Witherington, 393-94].

The act of laying on hands is a corporate affair in both texts. It involves the whole church in chapter 6. The subject of “they set . . . having prayed, they placed their hands on them” is the people (the Codex Bezae, D, sixth century, [in its] shift of responsibility from the people to the apostles reflects later church ecclesiology). The community elected and accredited the seven to the apostles. The latter made the seven representatives of the whole community by laying hands on them. In chapter 13 the laying on of hands is by the body of prophets and teachers. Barnabas and Paul are equals among these leaders now detailed for a special task. They are representatives, Rethinking the Meaning of Ordination 15 shaliachs, of the whole released (apoluo) for a special assignment. The release language may be significant. Barnabas and Saul are not “sent off,” as in most translations, but “cut loose.” They are freed from one ministry for another.

Neither Acts 6.6 or 13.3 look like ordination texts. Leaders are blessed for the gifts of the Spirit they already have, and are affirmed and released for specific ministry assignments by the laying on of hands.

Summary of New Testament Evidence

The practice of laying on hands for initiation into the Christian faith and

community is clear: 2 Tim. 1.6, Acts 8.17; 9.17; 19.6; Hebrews 6.2. Hands

are laid on new believers to bless them. This blessing is associated with the gift of the Holy Spirit to the new believers.

Two texts link the laying of hands and affirmation for church ministry:

Acts 6.6 and 13.3. Both are narrative texts. They report that people already gifted by the Spirit or already active in ministry were corporately affirmed for specialized ministries. No special gift, power, or position is involved in the laying on of hands.

The 1 Tim. 4.14 text is so ambiguous that it is not obvious if initiation

into the Christian faith or affirmation for ministry is the subject. Whatever the occasion, Timothy receives a charisma by means of a prophetic word.

In addition, other texts specifically speak of appointment to leadership tasks but say nothing about the “laying on of hands” or refer to any kind of ordination procedure. Barnabas and Paul “appointed (xeirotoneo) elders from among them (the disciples, v. 22) in every church” (Acts 14.23). Titus is appointed (xeirotoneo) to accompany Paul to Jerusalem with the offering that symbolizes the pilgrimage of the Gentiles to Jerusalem (2 Cor. 8.19). Titus is instructed to appoint (kathistemi) elders in every town (Titus 1.5). Leaders are being appointed for local congregational ministries and for very important trans-local, inter-congregational, even cross-cultural people-to people ministries, without any known legitimation by ordination. Or, there are texts that list leaders in local churches (e.g., Rom. 16, Phil. 4) that say nothing about ordination or commissioning to these ministries.

Light from the Old Testament and Judaism

The New Testament offers little evidence to support the church’s practice of ordination for ministry. But are we missing something by starting with the NT? Was not ordination practised in the Old Testament? And was not that practice continued in Judaism, for example, in the ordination of rabbis? It is not clear that ordination was practised in the OT. But the laying on of hands was practised. Could not that practice illumine the similar practice in the early church?

Laying on of Hands in the Old Testament

The laying on of hands is associated with four different events in the OT: 1) the transfer of the people’s sin to the scapegoat (Lev. 16.21); 2) the

consecration of the Levites (Num. 8.10); 3) Moses’s appointment of Joshua as his successor (Num. 27.18, 23; Dt. 34.9); 4) the communication of blessing or healing (Gen. 48.14ff.; 2 Ki. 4.34; 13.21).

The four events are described with two different words, samakh for

the first three, sim for the communication of blessing. David Daube has

proposed that the two words denote quite different things. Samakh means

“to lean upon for the purpose of transferring something in order to create a substitute or replacement.” It involves the pouring of one’s personality into the substitute (see Daube). Sim, in contrast, is a gentle term that means “to place on in order to bless.” It carries no connotation of transferring one’s personality or creating a substitute. When associated with sacrifice or the scapegoat offering of the Day of Atonement, samakh means to transfer one’s sins to a substitute so that it can bear the punishment instead of the person. Samakh is used for the consecration of the Levites because they as a class are created as a substitute for the firstborn in Israel (Lev. 8.15-19). Samakh also is used for the appointment of Joshua as Moses’s successor, suggesting that Joshua is his replacement or substitute.

M.C. Sansom has qualified the Daube thesis. Samakh, he argues, is a much more nuanced term than Daube suggests (Sansom, 323-26; see also D.P Wright, 433ff.). It has two meanings, “transference” and “acknowledgment or identification.” The term involves a transference only in two cases, the Day of Atonement ritual and the appointment of Joshua, and acknowledgment or identification in the other uses.

The two texts that narrate the appointment of Joshua do not indicate what, if anything, he received in the event. Deuteronomy 34.9 says he received the spirit of wisdom through the laying on of Moses’s hands. But Num. 27.18 says Joshua was commissioned because he already possessed the divine spirit. Furthermore, whatever was “transferred” in the laying on of hands, it was not in full measure as with Moses. God spoke face-to-face with Moses but Joshua will be instructed by Eleazar; Moses was the servant of God but Joshua is Moses’s minister (Joshua 1.1). N.H. Snaith asserts that the “laying on of hands” here “has nothing to do with any sort of ordination. Joshua already has the God-given ability. Moses lays his hands upon him before Eleazar in order visibly to lay his last commands on him” (Snaith, 311).

It is doubtful if the laying on of hands in samakh can be used as any

basis for a theology and practice of ordination in the OT. The term and the

practice is used in very restricted cases. The practice is never used for the appointment of priests or other religious leaders in the OT, e.g., the 70 elders of Israel (Num. 11.16ff.), prophets. Allen Guenther argues that “the word has nothing to do with the concept of ‘ordination,’ as we think of it” (Sept. 6, 1991 written note). Furthermore, none of the samakh passages influenced the practice of the early church. The same can be said of Judaism, as will soon be shown. The subsequent influence of the Joshua narrative is so minimal that J.K Parratt can say that the Joshua commissioning “has not exercised a normative influence upon either Judaism or Christianity” (212; cf. Warkentin).

What Happens in Judaism?

Most NT scholarship simply assumes that Second Temple Judaism continued an OT practice of ordaining by the laying on of hands, and that the early church adapted its practice from Judaism. Textual evidence, however, does not support this assumption. Samakh is used 150 times in the Mishnah, the authoritative Jewish interpretation of the Torah compiled around 200 CE, but all references deal with sacrifice, not with ordination to ministry (see Hoffman, 15-16). There also is no evidence in this or later literature for ordination by the laying on of hands. The texts are so silent that Lawrence Hoffman concludes “there was never any laying on of hands” (Hoffman, 17).

Leaders are ordained in Judaism. Three stages of the practice are

discernable. Up to around 135 CE individual rabbis ordain their disciples.

From 135 to 200 the Patriarch of Judaism alone is authorized to ordain. From 18 The Conrad Grebel Review about 200 on, the Patriarch and the rabbis of the Scholar Class together ordain. But three things must be noted. Evidence for the practice is too late (post-70 CE) to have influenced the early church. Secondly, it is never by the laying on of hands. The dominant practice seems to have been by proclamation,

but even the evidence for this is not clear. Thirdly, while many kinds of shaliachs (representatives or delegates) are appointed during this period, the procedures for such appointment are not obvious. In short, Judaism has an active practice of selecting and appointing leaders, but the procedures for affirming leaders is not at all clear. And there is no evidence for the laying on of hands.

Reading Back through the New Testament

Leaders are necessary for any movement; the life of the church depends on leaders. Therefore, Jesus called people “to follow” him and appointed them “to go preach, heal the sick, cast out demons . . . .” Christ gifts every church with ministers to enable and order the many gifts of the Spirit within the body so that the whole can be greater than the sum of the parts. Missionaries appoint leaders in young churches so that the church can be centered and grow (Acts 14.23; Titus 1.5).

What is striking in this theology and practice of church ministry is the

absence of any clear teaching or practice for the affirmation of leaders.

Leaders are important and necessary. Ministers are chosen or appointed.

Except for the missionary situation, the selection process always seems to

involve the whole congregation or the collective leadership of the church

(presybyteron). But there is little evidence for how these ministers were

affirmed (or ordained), and certainly no clear teaching on how this should be done. There is no evidence for something like the later church’s practice of ordination. Jesus did not “lay hands on” those whom he called and charged. The gift texts (Rom. 12, 1 Cor. 12, Eph. 4) say nothing about laying on of hands or any other form of public legitimation. The historic “foundation texts” for the practice of ordination to ministry are ambiguous at best. Timothy received a charisma through prophetic utterance and the laying on of hands at some point in his life, but that experience is not linked to a church leadership role. The two “laying on of hands” texts in Acts describe public blessing for gifts already given by the Spirit.

New Testament scholars are agreed that the few “laying on of hands” texts that we have do not suggest any creation of substitutes, or the transference of authority, or the imparting of personality. The laying on of hands is linked to the Spirit, corporate prayer, and blessing, not appointment to office or role. A series of scholars argue that the only OT linkage in laying on of hands is sim, blessing, not samakh (see Daube, 238-40; Ferguson, 1975, 2, and 1974, 284; Parratt, 213-14; Culpepper, 481). The laying on of hands accompanied by prayer confers a blessing and petitions the favor of God on the leaders gifted for ministry. The laying on of hands is an enacted prayer. This reading is reinforced by one of the early translations of the Greek New Testament: the Syriac translation used the equivalent of sim rather than samakh for the laying on of hands.

Ordination through the laying on of hands as the transference of

charisma, power, and authority is not taught or practised in the NT. What is practised is the affirmation of the gifts of the Spirit to the church for ministry and the blessing of God for those gifts.

One other body of NT evidence is relevant and important here. Scholars are agreed that apostles, prophets, teachers, and pastor-shepherds were not offices in the early church. They were not appointed or initiated by the community. These roles were gifts of the risen Christ to the church. What about the role of “elder”? Is this not a church office to which people were appointed by the laying on of hands? Alastair Campbell, following A.E. Harvey, has demonstrated that “elders” were senior men in the community and the leaders of influential families. Their position was recognized by custom, not by any kind of official appointment to a definable office. It denoted prestige, not office (Campbell; Harvey; see also Marshall, 172). So, again, laying on of hands recognizes what is; it does not confer anything new or empower for a new role.

So What?

This paper argues that ordination for ministry through the laying on of hands as practised in the church is without biblical foundation. There is no specific and clear textual basis for the theology and practice of “setting aside” for full-time ministry, for giving special status, and for legitimating authority and power for church office. Furthermore, the practice serves to divide clergy 20 The Conrad Grebel Review from laity, to undermine the teaching of the NT that leaders must be servants, and to contradict the NT’s repeated emphasis that all believers are called to and gifted for ministry.

In addition, there is no biblical linkage of personal call to ministry and

ordination through the laying on of hands, as practised in the protestant church. The laying on of hands on the seven in Acts 6 and on Barnabas and Saul in Acts 13 were not the community’s responses to an inner call sensed by these people; at least no call language is used in the texts. If the 1 Tim. 4.14 text speaks about laying on of hands for ministry, an interpretation challenged in this paper, no personal call to ministry is mentioned. The notion of an inner call to ministry and the ordination through the laying on of hands are never connected in the Bible or the early church. Affirmation for ministry is based on giftedness and community selection, not an inner sense of call. The seven in Acts 6 and Barnabas and Saul in Acts 13 first learned of a call from the church, not from an inner experience. If the call of the church was later confirmed through an inner sense of call, we are not told about it. The church called, the church affirmed through the laying on of hands, the people so called and affirmed ministered (see Falk for a thorough biblical challenge to the idea of “call” to ministry, and Culbertson and Shippee for the skepticism of the early church about personal calls).

If laying on of hands does not mean ordination as sacrament – the

view of the Roman Catholic Church and many protestant churches that it

communicates grace and gifts that profoundly shape character and confer

special rights and duties, or ordination as authorization – the view of Luther and Calvin that it confers authority to preach the Word and administer the sacraments, what does it mean? It could mean commissioning for service. The seven in Acts 6 and Barnabas and Saul in Acts 13 had hands laid on them to commission them to a particular “work.” The laying on of hands in commissioning says that the church believes that God has gifted “these people” with gifts for a particular ministry, and the church commissions “these people” for this ministry.

Or, the laying on of hands could mean church confirmation and blessing. Again, the seven in Acts 6 and Barnabas and Saul in Acts 13 were gifted by the Spirit before the call of the church. The laying on of hands is a confirmation of the gift(s) of God and a prayer of blessing to God for the fruitful exercise of these gifts in ministry.

A careful reading of the biblical texts would hardly permit meanings

other than commissioning or confirmation/blessing. But that is to address the issue only on the basis of specific texts. The question of how the church selects and affirms its leaders must be based on more than specific texts whose meaning is ambiguous. It must ultimately be based on a theology of church. If the church is a peoplehood, a community, a body, a family of God (see Toews, 1989), then that theology must shape its theology of ministry affirmation. Such a theology calls for both a theology of ministry and a practice of ministry affirmation that is consistent with the nature of the church discerning/calling and affirming people. Ministers in the church cannot be self-chosen but must be called out by the church. The criteria for such discerning and calling are a servant spirit, giftedness for ministry, and godly character. The ministers are publicly commissioned and blessed by the church. The churchly laying on of hands together with prayer is an appropriate way to bless and commission for a specific ministry.

Because ordination language is so loaded with “sacramental,” “authorization,” and “proper succession” baggage, the church should not use it to describe or to understand the meaning of the laying on of hands. Such a desacramentalization will free the church from a host of problems – e.g., ordination as status and power, ordination for life, clergy-laity distinctions – and free it to lay hands on many people to confirm and bless them for ministry in and for the church.

An Historical Postscript

If ordination to church ministry is without clear biblical foundation, what is the origin of the theology and practice? It emerged in the third century of Christian history. The development of a theology and practice of ordination is part of a much larger ecclesiological development, the centralization of church power and authority, the development of a clergy (priestly) class distinct from the other members in the church (laity), the sacramentalization of the Lord’s Supper (see Culbertson and Shippee, Faivre, Hinson, Volz). David Bosch makes the case that “the institutionalization of church offices” was one of the characteristics of the Constantinian dispensation. “The clericalization of the church,” he continues, “went hand in hand with the sacerdotalizing of the 22 The Conrad Grebel Review clergy” (Bosch, 467-68). The history of this development is very instructive, and alone should give churches in the believers or free church tradition pause in the use of a practice that fundamentally contradicts their theology of church and church ministry.

What Then Shall We Do?

If we grant the argument of this paper, what shall we do practically in the church? I suggest the following: 1) discontinue the use of ordination language and practice, and unhook affirmation for church ministry from all forms of privilege and status (e.g., offices, titles, special tax deductions). 2) Teach that ministry belongs to the whole people of God; every Christian is gifted for ministry. 3) Teach that there are ministry gifts whose function is to enable and order the many different gifts in the church. 4) Practice the discernment of gifts in the church. 5) Base selection for church ministry on the discernment of the church, not on the notion of personal call. 6) Recognize that authority in ministry derives from the character of the minister and the ministry accepted and discharged, not from status or official legitimation. 7) Develop a creative ceremony to bless and commission people called by the church for specific ministries.

Blessing/commissioning services would thus replace ordination

services. By definition blessing/commissioning services are both more inclusive and more limiting. They are more inclusive in that the many ministry gifts in the church can be blessed/commissioned regularly, e.g., Sunday school teachers, school teachers, administrators, healers, pastors, evangelists. They are more limiting because the blessing/commissioning would be for a specific task, e.g., pastoring a specific church, shepherding a conference of churches, administering an institution or agency of the church, teaching Sunday school for the current year, planting a church in a specific location.

I conclude with an email exchange with John Esau, formerly of the

Ministerial Office of the US General Conference Mennonite Church. He

was one of the people to whom I sent a draft copy of this lecture for feedback. He recognizes the nonexistence of biblical foundations for the practice of ordination. But he wants to keep the practice and reframe it “in the direction of a blessing of the church,” and thereby “endow it with meanings appropriate to Anabaptist Mennonite theology” (Oct. 7, 2003 email). My response to John was that “the practice of ‘ordination’ undermines, even contradicts, that goal. Ordination theologically, historically, ritualistically, and practically sacerdotalizes the role of church ministry – it confers special status and privilege by the state, by society, and by members of the church, if we like it or not. The ritual of ordination itself creates a world view and value system. That is, rituals are more than external signs of inner realities. They, in fact, define realities, and the reality created by the ritual of ordination is a sacerdotal one – it sets a person apart and grants special status and privilege. Add to that the problematic of the Constantinian baggage, and I think we have a practice that we cannot ‘endow with meanings appropriate to Anabaptist Mennonite theology.’ We need a new ritual that defines what we want to say in ‘blessing’ or ‘commissioning’ a person for ministry in the church” (Oct. 24, 2003 email).

See the response to this article by Loren L. Johns.

Bibliography

A Mennonite Polity for Ministerial Leadership, Everett J. Thomas, ed. Faith and Life Press, 1996.

Adrian, Victor, “The Call and Ordination to the Ministry.” Unpublished Study Conference Paper, General Conference Study Conference, 1980.

Barrett, C.K., The Acts of the Apostles. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary, vol. 1. T & T Clark, 1994.

Bassler, Jouette M., 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus. Abingdon New Testament Commentaries. Abingdon, 1996.

Bosch, David J., Transforming Mission. Orbis, 1991.

Brug, John F., “Ordination and Installation in the Scriptures.” Wisconsin Lutheran Quarterly 92 (1995): 263-70.

Campbell, R. Alastair, The Elders. T & T Clark, 1994.

Collins, Raymond, I and II Timothy and Titus. New Testament Library. Westminister/John Knox, 2002.

Countryman, L. William, The Language of Ordination. Trinity Press International, 1992.

Craige, P.C., The Book of Deuteronomy. New Internation Commentary on the Old Testament. Eerdmans, 1976.

Culbertson, P.L. and Shippee, A.B., eds., The Pastor. Readings from the Patristic Period. Fortress, 1990.

Culpepper, R.A., “The Biblical Basis for Ordination.” Review and Expositor 78 (1981): 471-84.

Daube, David, “The Laying on of Hands.” The New Testament and Rabbinic Judaism. Arno Press, 1973.

Dibelius, Martin, and Conzelmann, Hans, The Pastoral Epistles. Hermenia. Fortress, 1972.

Faivre, A., The Emergence of the Laity in the Early Church. Paulist, 1990.

Falk, David J., “A New Testament Theology of Calling with Reference to the ‘Call to Ministry.’”MCS Thesis, Regent College, 1990.

Fee, Gordon, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus. Good News Commentary. Harper, 1984.

______, “Laos and Leadership under the New Covenant,” Crux 25 (1989): 3-13. Ferguson, Everett, “Laying on of Hands: Its Significance in Ordination.” Journal of Theological Studies 26 (1975): 1-12.

______, “Selection and Installation to Office in Roman, Greek, Jewish and Christian Antiquity,” Theologishe Literaturzeitung, 30 (1974): 273-84.

Fitzmyer, Joseph A., The Acts of the Apostles. Anchor Bible. Doubleday, 1998.

Flemming, Dean, The Clergy/Laity Dichotomy,” Asian Journal of Theology, 8 (1994): 232-50.

Geddert, Timothy, “Ordination.” Unpublished Study Conference Paper, General Conference Study Conference, April 1994.

Giles, Kevin, Patterns of Ministry among the First Christians. Collins Dove, 1989.

Guthrie, Donald, The Pastoral Epistles, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries. Tyndale, 1957.

Hanson, A.T., The Pastoral Epistles, New Century Bible. Eerdmans, 1982.

Harvey, A.E., “Elder,” Journal of Theological Studies 25 (1974): 318-31.

Heidebrecht, Harry, “Toward a More Biblical View of Ordination.” M.Div. Thesis, Mennonite Brethren Biblical Seminary, 1971.

Hinson, E. G., “Ordination in Christian History.” Review and Expositor 78 (1981): 485-96.

Hoffman, Lawrence A., “Jewish Ordination on the Eve of Christianity.” Studia Liturgica 13 (1979): 11-41.

Humphrey, Fisher, “Ordination and the Church,” The People of God. Essays on the Believers’ Church. Paul Basden, David S. Dockery, eds. Broadman, 1991. 288-98.

Johnson, Luke Timothy, The Acts of the Apostles. Sacra Pagina Series. Liturgical Press, 1992.

Kelly, J.N.D., A Commentary on the Pastoral Epistles. Harper New Testament Commentaries. Harper, 1963.

Kilmartin, Edward J., “Ministry and Ordination in Early Christianity against a Jewish Background.” Studia Liturigica 13 (1979): 42-69.

Kiwiet, John J., “The Call to the Ministry among the Anabaptists.” Southwestern Journal of Theology 11 (1968-69): 29-42.

Knight, George W., The Pastoral Epistles. New International Greek Testament Commentary. Eerdmans, 1992.

Marshall, I. Howard with Philip H. Towner, The Pastoral Epistles. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary. T & T Clark, 1999.

Mayes, A.D.H, Deuteronomy. New Century Bible. Attic, 1979.

Meier, John P., “Presbyteros in the Pastoral Epistles,” The Mission of Christ and His Church. Studies in Christology and Ecclesiology. Michael Glazier, 1990.

Miller, Patrick D., Deuteronomy. Interpretation. John Knox, 1990.

Ministers Manual, ed. John Rempel. Herald Press, 1998.

Morris, Leon, Ministers of God. InterVarsity, 1964.

Oden, Thomas C., First and Second Timothy and Titus. Interpretation. John Knox, 1989.

Parratt, J.K., “The Laying on of Hands in the New Testament.” Expository Times 80 (1968-69): 210-14.

Peacock, H.F. “Ordination in the New Testament.” Review and Expositor 4 (1958): 262-74.

Peters, F.C., “Quo Vadis: Mennonite Brethren Church.” Mennonite Brethren Herald 8 (September 5, 1969): 2-4.

Regehr, John, “The Call to Ministry.” Unpublished Study Conference Paper, Canadian Conference, 1976.

Sansom, M.C., “Laying on of Hands in the Old Testament.” Expository Times 94 (1983): 323-26.

Schweizer, Eduard, Church Order in the New Testament. SCM, 1961.

Snaith, N.H., Leviticus and Numbers. New Century Bible. Nelson, 1967.

Talley, Thomas J., “Ordination in Today’s Thinking.” Studia Liturgica 13 (1979): 4-10.

Toews, John E., “Leadership Styles for Mennonite Brethren.” Unpublished Study Conference Paper, General Conference Study Conference, 1980.

Toews, John E., “The Nature of the Church.” Direction 18 (1989): 3-26.

Verner, David C., The Household of God. The Social World of the Pastoral Epistles. SBL Dissertation Series 71. Scholars Press, 1983.

Volz, C.A., Pastoral Life and Practice in the Early Church. Augsburg, 1990.

von Rad, Gerhard, Deuteronomy. OT Library. Westminster, 1966.

Warkentin, Marjorie, Ordination. A Biblical-Historical View. Eerdmans, 1982.

Wenham, Gordon J., Numbers. Tyndale OT Commentaries. InterVarsity, 1981.

Wiebe, Orlando, “The Commissioning of Servants in the Church.” Unpublished Study Conference Paper, General Conference Study Conference, 1970. Published in The Journal of Church and Society 6 (1970): 2-22.

Witherington, Ben III, The Acts of the Apostles. A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. Eerdmans, 1998.

Wright, David F., “Ordination.” Themelios 10 (1985): 5-10.

Wright, David P., “The Gesture of Hand Placement in the Hebrew Bible and in Hittite Literature.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 106 (1986): 433-46.

Yoder, John H., “The Fulness of Christ.” Concern, 17 (1969): 33-93

The Conrad Grebel Review 22, no 1 (Winter 2004)

This paper argues that ordination for ministry through the laying on of hands as practised in the church is without biblical foundation. There is no specific and clear textual basis for the theology and practice of ‘setting aside’ for full-time ministry, for giving special status, and for legitimating authority and power for church office. Furthermore, the practice serves to divide clergy from laity, to undermine the teaching of the NT that leaders must be servants, and to contradict the NT’s repeated emphasis that all believers are called to and gifted for ministry. . . . The question of how the church selects and affirms its leaders must be based on more

than specific texts whose meaning is ambiguous. It must ultimately be based on a theology of church. — John E. Toews

Toews’s Argument Described and Considered[1]

In his article on ordination and pastoral leadership, John E. Toews identifies ordination as an odd and unbiblical practice. Tracing briefly the story of the Mennonite Brethren on this matter and his own story, which includes significant interest in and many years of service in support of pastoral leadership, Toews reviews the biblical evidence for ordination. Biblical evidence in support of our current practice of ordination is lacking – something that even strong advocates of pastoral ministry and ordination in the Mennonite Church freely admit,[2] though with different conclusions. While its practice in the Roman Catholic Church and some Protestant traditions may be understandable in light of their ecclesiologies, it clearly is not consistent with an Anabaptist or Mennonite ecclesiology.

The problem, says Toews, is that

the act of ordination in many churches is viewed as a sacramental event – it confers lifetime grace, authority, and status. While many Protestant churches, including Mennonite churches, have tried to de-sacramentalize ordination, the long-time underlying assumption and reality is sacramental. It continues to confer lifetime status, it is understood as ‘a life-shaping and identity-giving moment’ (Mennonite Polity, 30), it places one into a special ‘office of ministry,’ and it confers special privileges and status.

Toews suggests that later ecclesiological interests in church order,

hierarchy, and apostolic succession have schooled us to read some of the

New Testament texts in anachronistic ways.[4] Thus, when we see references to “the laying on of hands” in the NT, we are tempted to think of some kind of ordination rite, even when the context makes clear that these passages (cf. 1 Tim. 5:22; 2 Tim. 1:6; Acts 8:17; 9:17; 19:6; Heb. 6:2) refer to the initiation and incorporation of people into the Christian church through the gift(s) of the Holy Spirit. The decision of the NRSV translators to substitute ordain for lay hands on in 1 Tim. 5:22 would be an example of translators going too far in their interpretation of the text as they translate – or at least of making the wrong interpretive decision in their translating.

Points of Critique

In commenting on the meaning of the laying on of hands in the NT, I think

Toews goes too far in pressing the distinction between “initiation and

incorporation of people into the Christian church” and “the imparting of spiritual gifts.” He neatly categorizes all the above passages as examples of the former, and Acts 6:6 and 13:3 as examples of the latter. However, even when initiation and incorporation of new believers is clearly in view and not commissioning to some specialized ministry of leadership, the imparting of the gift(s) of the Holy Spirit are nevertheless present as well (see esp. Acts 8:17; 9:17; and 6:6). Furthermore, the laying on of hands is not just a symbolic “rite of initiation,” but also an actual imparting of giftedness for ministry – ministry understood not as pastoral leadership but as the task of every Spirit-filled believer. Even if this is a “sacramental” view of the laying on of hands, I would agree with Toews that it certainly is not sacerdotal. Nevertheless, the biblical texts seem to indicate that the rite was more than symbolic; it was also effective.

Toews’s biblical work may seem to reflect a restitutionist hermeneutic

– the view that the church order of the earliest church is ideal and that later developments in church order are by definition a fall from it. Restitutionists seek to define church order and structure by replicating a harmonized view of the church order(s) reflected in the NT.[5] But Toews recognizes that we do a lot today that the early church did not practice. We are not, and should not be, bound by biblical precedents in our conception of church order, for we recognize God’s Spirit did not suddenly cease to function with the close of the NT canon.

If there is a “yawning gulf” between the early Paul and the Pastoral

Epistles, or between the Pastorals and the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus over a century later, we should not assume that the later developments were necessarily a fall from the ideal. The developing structures and orders in the church may have been God’s gift for new times, and it is just possible that Hippolytus reflects God’s will for the contemporary church more than the Pastoral Epistles with respect to church offices. Toews’s argument is not truly restitutionist in character. He recognizes that it is not enough to say that ordination is not specifically taught or practiced in the NT. His point is that its practice is not in keeping with the teaching or practices of the NT. Thus, it is not just a matter of New Testament silence on the issue; it is a matter of its essential incompatibility with NT teaching.

Although modern Anabaptists recognize that it is legitimate to make

room for the authority of tradition and experience alongside the authority of Scripture in practical matters, it is difficult to know how and where to find the right balance. Historically, the church has suffered much corruption in taking too seriously the authority of later church tradition and too lightly the examples and teachings of the Bible. Toews would say that he is not rigidly idealizing the early, but recovering a biblical ecclesiology that is thoroughly grounded in

The question is whether Toews’s call for our discontinuation of ordination responds flexibly and appropriately enough to the needs of the church in today’s context. Answering such a question requires careful listening to the Holy Spirit as well as to church tradition and experience.biblical conceptions of the purposes and callings of God for it.

Assessment of the Argument by Means of Practical Considerations

So how should we interpret the Bible in light of the realities of our culture

today? By focusing on what does and does not follow from Toews’s reading of the Bible in terms of practical implications, I hope to clarify and test his reading. On many of the issues he addresses, I believe Toews is on target – correct in the observations he makes and in the conclusions he draws for the life of the church. A consideration of several practical questions might help to test this assessment.

1. Does Toews really want us to do away with ordination? In challenging

the very practice of ordination on the basis of its sacramental character

in many traditions, is he not in danger of throwing the baby out with the

bathwater?

Yes and no. Toews would say that we need some way to bless, commission, install, and publicly recognize the particular calling and role that a pastor has, but that we should modify its practice, our understandings of it, and our terminologies for it to bring it into line with the Bible and with Mennonite ecclesiology.

It is clear to me that in the NT, church leaders laid hands on others to commission or authorize them for specific ministries. In so doing, gifts of the Spirit were imparted, just as they were imparted to all believers for ministry. Toews does not challenge the validity of recognizing and authorizing individuals for pastoral ministry or other leadership roles in the church; what he is objecting to is primarily the elitist and classist implications that often accompany ordination.

How we have ordained and what we have made of it is admittedly

problematic. However, since Toews does not challenge the idea that we need pastors or that they should be installed, blessed, and commissioned in some way, can we not work at investing new meanings and understandings into our rituals of installation/blessing and even in our use of the word ordain? Toews emphasizes the significant problems with doing so. He says that ordain has been so irretrievably sacerdotalized in its implications that we can no longer reinvest in it a more proper understanding of what the rite does or entails. The very words ordain and ordination carry with them notions of lifelong class, status, and a formal distinction between clergy and laity. These associations are not biblical and not in keeping with Anabaptist ecclesiology, he says. As a result, we need to learn to use other words like bless or commission in its place.

I used to agree with Toews on this point. However, several considerations have helped me change my mind. First, many ordinary Mennonites would say that when we ordain, we are setting a person apart for a particular ministry – not in the sense of creating a class, status, or formal distinction between clergy and laity, but in the sense of recognizing and authorizing individuals for pastoral ministry or other leadership roles in the church. That is what we are doing in ordination. Second, many Mennonite churches have already made progress in creating new understandings of ordain. For instance, in most of the conferences I know, ordination is no longer for life but implies and entails accountability to the church. I am thus more optimistic than Toews about the possibility of changing our understandings of ordination in a more biblical direction while retaining our practice of it as well as the terminology of ordination.

I was ordained for pastoral ministry in 1978. When I left the pastorate in 1985 to become theology book editor for Herald Press, the conference of which I was a part thought there was some reason for retaining my ordination credentials for the ministry to the church that I was doing as book editor. Even so, I was required to periodically engage in conversations to ensure that I was being appropriately accountable to my local congregation as well as to the broader church in that ministry. I welcomed that accountability and respected the expectation. It helped establish an understanding of ordination credentials as conferring authority and leadership responsibilities, while at the same time undercutting elitism or personal status. Today, I serve as dean of AMBS; my ordination credentials are renewed annually for similar reasons.

If we can invest in the word ordination proper understandings in

keeping with our ecclesiology as a Mennonite church – and that is one of the key questions here – then there is much to be gained in retaining the

terminology. This is work that we can do – work that has already been done. I like John Esau’s attempt to define ordination in ways that are appropriate to our ecclesiology:

Ordination should be interpreted within the church to be about

responsibility and accountability. It is a rite that belongs to the church by which the church lays claim upon those who would serve in ministerial leadership roles. It is intended to clarify relationships, roles, and responsibilities. Another way to say this is that the office of ministry belongs to the church, not to those to whom it is entrusted and symbolized through ordination[6]

Ordination is thus not “about me” so much as it is about how my ministry is recognized by the larger ecclesiological movement of which I am a part. Dorothy Nickel Friesen defines it similarly: “Ordination is a churchly rite that connotes power, authority, and responsibility to the Body of Christ, to the call of God, and to the release of spiritual gifts possessed by the individual. This three-way combination needs and deserves a status that is unique and honorable.”[7]

It is not as important for me as it once was to be ordained; the church has already commissioned me, authorized me, and installed me as academic dean, making my ordination credentials somewhat superfluous.[8] If I were to give up or lose these credentials, I do not think that this would weaken my standing in the church or my ability to operate effectively as a seminary dean. This is not the case for young pastors or for women or for others who more pressingly need the clear commissioning and authorizing of the church that ordination provides. My concerns about ordination do not derive from my own privileged status or power. It is not as though I have the luxury of being able to question the value of ordination, now that I no longer have the need for its authorization; I have long had deep convictions about the radical nature of the NT view of giftedness and ministry and have written about these matters in the 1980s. With or without ordination, leaders need the formal affirmation and authorization of the community. But such affirmation and authorization do not convey status, except insofar as all believers have special status, given their unique gifts and callings.

Finally, Toews does not adequately consider the ecumenical challenges that dispensing with ordination would entail. In most ecumenical contexts, ordination is synonymous with the church’s authorization of an individual to play a representative and leadership role. Without ordination, pastors in the Anabaptist family of churches would need to try to explain again and again how and why it is that they are properly recognized and authorized as leaders in the church, and why it is that we nevertheless do not practice “ordination” but we do practice something like it. Eliminating ordination would cut us off from our shared understandings, even if we maintain important differences in our understanding of the word and of the rite. Critical theological selfdifferentiation is important, but certainly not for its own sake. As Diane Zaerr Brenneman asks, “Dare we be so different in the way we credential leaders 32 The Conrad Grebel Review that post-modern Americans cannot figure out how to navigate our churches?”[9] John Esau is right to say that what we Anabaptists share with our brothers and sisters in other theological traditions – both in critique and in affirmation – is greater than what we differ on. Servanthood understandings, the priesthood of all believers, accountability, the call for a life consistent between profession and practice – all of these are common themes.[10] We must be careful about smug confidence about having a corner on the truth in these matters.

2. Does Toews wish to eliminate the clergy/laity distinction?

Absolutely! This essentially classist distinction owes itself historically to the influence of high church ecclesiologies that, in both their Constantinian and Magisterial Reformation forms, were highly invested politically in a

disempowered laity. I fully agree with Toews that it is time for contemporary Mennonites in the Anabaptist tradition to repudiate such an unbiblical distinction. Classism does not empower the pastorate nor does it meet the needs of the church for effective leadership. The answer to this problem is not to disempower the pastorate as we did in the anti-authoritarian egalitarianism of the 1960s and ’70s, but to place a respected and honored pastorate within the context of empowered congregations full of gifted and ministering believers. Active Spirit-empowered congregations are a gift to pastors.

Empowerment and disempowerment are both relative and subjective.

Depending on one’s perspective, the empowerment, recognition, or honoring of any person or persons in the church automatically entails the

disempowerment, lack of recognition, or dishonoring of other persons in the church. I don’t believe it. Surely we can do better! I like how Keith Harder has put this matter in response to my comments on ordination:

In taking this step [i.e., in accepting ordination], I was keenly

aware that the congregation would tend to see me primarily as a paid professional doing ministry on behalf of the church, which would tend to compromise and undermine my deeply held conviction that all are called to ministry and service. But I came to see that one of the best reasons for me to accept ordination is that it would actually help and empower me to equip and empower others for their ministries. It was not ultimately about the power that accrued to me in being ordained but it was much more about empowering others for their ministries that we might all embrace the task of building up the body of Christ and her witness to the world. As I reflected on my previous ministry experience and on other

churches that had rejected ordination, it was not obvious to me that they were any more successful in calling and equipping everyone for ministry. The rejection of ordination too often was coupled with suspicion of leadership that seemed to compromise the ministry of all even more than the practice of ordination. The challenge for those who are ordained is to use their ‘office’ for what it is intended – to equip the saints for ministry. I have come to believe that

ordination can actually contribute to that end, if the ordained are clear about this purpose and actively work to equip others for ministry.[11]

Power itself is not the problem. Certainly it is subject to misuse and abuse,

but “we still need and value power, whether in persons who use it accountably or in institutions that use it for the common good.”[12]

3. If Toews is correct in his assertion that our current understandings

and practices of ordination are so unbiblical and out of sync with our

ecclesiology, how did we get to where we are today?

This question deserves a fuller recital of history than I am able to provide, and the answers undoubtedly differ somewhat for each stream in our Anabaptist- Mennonite family. Toews referred to the “Concern Group,” debates in the Dean’s Seminar at AMBS, and the work of John Howard Yoder, all of which served to raise questions in the Mennonite Church tradition about ordination similar to those Toews raises. I suggest that in the last twenty years the church has ignored its misgivings about ordination for pragmatic reasons.

First, we wanted to honor pastors and the pastoral ministry, and so we have been reluctant to do anything that would undermine the class distinction to which ordination contributes. Second, the rite of ordination has been experienced as empowering by pastors. When they have had doubts or misgivings about their calling, its memory has served as a reminder that, yes, God and the church had indeed called them to this task. We did not want pastors to second-guess their callings. We have other means at our disposal to confirm and reassure pastors in their callings besides resorting to classist structures. Third, the Mennonite Church has been busy courting and marrying a General Conference tradition that has not generally shared these misgivings. I am convinced that the old MC and GC traditions still have things to learn from each other on this score – not because the truth must be in between somewhere, but because their differing histories have taught differing lessons that are important and valid. Fourth, women have always needed to deal with

an inferiority of class imposed both within and without the church in ways

with which men have not needed to contend. As women have been received as pastors to greater or lesser extents, ordination has served to confer and confirm their class superiority along with ordained male pastors. Without ordination, women in ministry would face a continuing challenge of class and status that men in ministry simply would not need to face.

Our perceptions of what corrections are needed, and what we are

thus prepared to argue for, are dependent to a great extent upon our particular experiences of life and the lacks we have experienced. Some of us are much more impressed with the dangers of authoritarianism and status than we are with the postmodern morass. For others, it is the opposite. As Andy Brubacher Kaethler has observed, “Some postmodern pastors are so inherently sceptical of institutionalized authority that the danger we face comes from the other direction of not taking it seriously enough. ‘Set apart’ does not necessarily mean ‘set above.’”[13] We need to pay attention to what the Spirit is saying to us, keeping our ears open especially to those with experiences different from ours. While pragmatic considerations are understandable, we must not be opportunistic in our consideration of the theological and practical issues here.

4. Won’t Toews’s proposed elimination of the clergy/laity distinction harm

our efforts to develop and sustain a culture of call in today’s church?

No. It will actually support and enhance it. I lament when people ask whether God has “called them to the ministry.” It is a bad question and harmful to the church, since it wrongly implies that the answer could be no. The NT affirms that every believer is called to ministry for the sake of the church. As believers, we should not attempt to discern whether God is calling us to ministry; God is always calling all of us to ministry. The much better question is, To which ministry is God calling me in this time and place? I am not suggesting that the Holy Spirit calls or gives gifts in only episodic ways; I believe that some callings and gifts have some durability and portability. I am suggesting only that the call to ministry requires the ongoing discernment and affirmation of the church. In perhaps more ways than Toews allows, the church is already functioning accordingly: we routinely evaluate the effectiveness of our pastors’ ministries.

When I was in college, three other guys and I lived off-campus and led a weekly worship and Bible study for some of our peers at Goshen College. This went on for three years. Every week we provided leadership as the group got together, prayed, sang with guitars, studied the Bible, supported each other, and sought God’s will. In the course of those three years, each of us began to sense a call to ministry. As it turned out, all four of us later served as pastors. Although none of us are currently pastors, I believe that each of us is continuing to fulfill our calls to ministry. Even as I was wrestling with that call in college, I believed that my call was to a ministerial leadership role in general, rather than to pastoral ministry specifically. (As it turned out, I have “ministered” as a pastor, theology book editor, college Bible professor, and seminary dean – and just as importantly in other, nonprofessional ways, such as a listening friend.) This made that call no less important to discern. I do believe that God calls some people specifically to pastoral ministry. But I also believe that the future of the church and of God’s unfolding reign on earth depends much more on every believer hearing and responding to God’s

ongoing calls to ministry than it does on future pastors hearing the specific

call to pastoral ministry.

The clergy/laity distinction actually makes it much more difficult for

young people to consider the call to pastoral ministry, for a variety of reasons. First, some seminary students struggle with the discernment because they find it hard to believe that God is calling them to be like the pastors they have experienced. At AMBS we occasionally emphasize that God may be calling our students to serve as pastors even if they do not look or act like the pastors they have known – or want to do so. Congregations and pastorates are marvellously diverse in character; how much more are the gifts of the Spirit in empowering all of the members of the Body! Second, we are not used to affirming on a routine basis the responsibility of all believers to fulfill their calls to ministry in general. As we correct this – as we begin to expect, 36 The Conrad Grebel Review

experience, and benefit from the ministries of all believers, it will be much

easier to affirm youth (and others) in their actual practice of various ministries. It will become much more natural for the church to recognize the gifts of leadership in a few, and it will be easier for the youth to imagine themselves in those ministries. Third, ministry experiences help one imagine pastoral ministry as a calling. That is what happened to me in college. There is a kind of natural progression from ministry to leadership in ministry to pastoral ministry. As youth grow in ministry experiences, it will be easier for them to imagine added leadership responsibilities in those experiences, and eventually the pastoral role.

5. Do pastors have a unique calling and a unique role to play in the

church that deserves honor and respect?

Yes. Here I imagine Toews would say that the pastoral role is unique – just as every other role in the church is unique in its own way. The church needs leaders and the NT recognizes and affirms that need. However, Paul takes pains in 1 Cor. 12–14 to establish that all of the gifts and offices in the church are deserving of honor. “Our presentable parts need no special treatment” (1 Cor. 12:24, NIV). Even if Paul can identify some gifts as worthy of more honor than others (“God has appointed in the church first apostles, second prophets, third teachers …” [1 Cor. 12:28]), no one can say that he or she does not need the less honorable gifts of the body. Those who are pastors or overseers do deserve honor, but so do all of the members of the body. What is most important is love (1 Cor. 12:31b–13:13) and whatever equips and builds up the Body of Christ (Rom. 14:19; 15:2; 1 Cor. 14:1-5, 12, 26).

In my introduction to Erick Sawatzky’s The Heart of the Matter:

Pastoral Ministry in Anabaptist Perspective, I asked a series of rhetorical

questions: Is it possible to reform our understanding of ministry in such a

way that recognizes the particular calling and giftedness of pastors